|

Summer 2006

(14.2)

Pages

56-65

Politically

Correct Music

Stalin's Era and the Struggle of Azerbaijani Composers

by Aida Huseinova

The

last century of Azerbaijan's history of music has been marked

by successful premieres and triumphal performances, but juxtaposed

against those achievements are tragic stories of torment, censorship,

and psychological pressure that many of the nation's prominent

musicians faced during the Stalinist era (1920s to 1950s). The

last century of Azerbaijan's history of music has been marked

by successful premieres and triumphal performances, but juxtaposed

against those achievements are tragic stories of torment, censorship,

and psychological pressure that many of the nation's prominent

musicians faced during the Stalinist era (1920s to 1950s).

For decades, we proudly boasted of the tremendous success of

Hajibeyov's "Koroghlu"

[Son of a Blind Man]("Koroghlu" was composed by Uzeyir

Hajibeyov and the libretto was written by Mammad Sayid Ordubadi

[1872-1950].), which made its debut in the late 1930s. We were

unaware that the opera by Uzeyir Hajibeyov (1885-1948) featuring

the theme of the masses rising up in rebellion against feudal

lords may have saved the composer's life.

Now we understand that political realities forced the composer

to manipulate this theme, reconciling it with Communist ideology

rather than follow the legendary reality of the region. (The

enemy in Hajibeyov's Koroghlu is depicted as Turks, rather than

Persians, as the legend holds forth. See "The

Other Koroghlu: Tbilisi Manuscript Sheds Light on Medieval Azerbaijani

Hero" by Dr. Farid Alakbarli. AI 10.1 (Spring 2002).

Yet the performance of Koroghlu became Azerbaijan's crowning

glory at the Decade of Azerbaijan Art in Moscow in 1938. Stalin

appeared in the audience and praised it. For Hajibeyov, it helped

to ease some of anxiety he had felt for more than two decades

when he was targeted for his "suspicious" pre-Soviet

past, especially in relationship to his own involvement (along

with his brother Jeyhun) with Azerbaijan's independence movement

which led to the establishment of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic

(1918-1920) and with writing its National Anthem.

We used to lament the early death of the gifted jazz musician

Parviz Rustambeyov, but we never revealed that he had been arrested

for political reasons and died in prison.

Only now, after gaining independence from the Soviet Union in

late 1991, have some of these documents been found in archives,

which for so long have barred their tragic secrets from us. The

truth they reveal has shocked many of us.

Radicalism of the 1920s Radicalism of the 1920s

"On behalf of tomorrow, let us burn Rafael, destroy the

museums and trample the flowers of art." This was one of

the major slogans of some of the radical followers of the Communist

ideology. Under the ideology referred to as Proletkult (proletarian

culture), they declared war on the cultural heritage of all Soviet

nations.

This radical attitude led to campaign attacks against two musical

phenomena in Azerbaijan. First, the apologists of Proletkult

began attacking the use of Azerbaijan's national instruments,

specifically the tar, traditional stringed instrument, which

had been used for centuries.

("Sing Tar, Sing". See the arguments related to

eliminating tar music from the diaries of Dilbar Akhundzade whose

husband Mikayil Mushfig (1908-1939) wrote the lines "Sing,

Tar Sing" in AI 10.3 (Autumn 2002). Also see "'Sing Tar,

Sing': Like Father, Like Son. Passing on the Tradition,"

by Betty Blair. AI 7.4, (Winter 1999).

Secondly, they began severely criticizing the genre of "mugham

opera"(Mugham opera is a unique hybrid genre where the general

concept obviously draws upon an opera: performers sing on stage

accompanied by a symphony orchestra, and the entire composition

is divided into several acts. However, all classical operatic

forms are replaced with mughams-traditional modal music. The

first

performance of a mugham opera took place in 1908 with "Leyli

and Majnun" by Uzeyir Hajibeyov and this work is referred

to as the "First Opera in the Muslim East".

For a short history and synopsis of the first mugham opera, see,

"Leyli

& Majnun" in AI 9.3 (Autumn 2001) (See also HAJIBEYOV.com.)

which was a synthesis of genres of West (opera) and East (Mugham

or modal music)] which had been the first example of composed

art music tradition in the country.

The first generation of national composers, notably Uzeyir Hajibeyov

(1885-1948) and Muslim Magomayev (1885-1937), were personally

attacked since their vision of the future development of Azerbaijani

music integrated tar and mugham opera as its primary components.

Had the Communists succeeded in reaching their goals by declaring

this traditional instrument and this genre a relic of the past,

and in convincing Azerbaijanis that these first national composers

were incompetent, then the development of contemporary Azerbaijani

music would today resemble a blank sheet of paper covered with

red letters of Soviet history. Fortunately, this never happened.

The campaign against tar and mugham opera was led by the Minister

of Culture Mustafa Guliyev, an arduous apologist for the Russification

of Azerbaijani music. He involved politicians, journalists, writers

and musicians in his attacks.

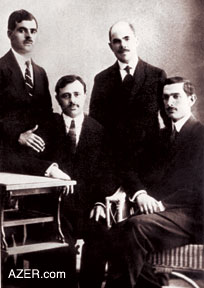

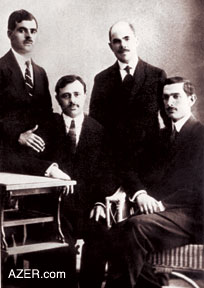

Left: Huseingulu Sarabski, Uzeyir Hajibeyov, Hanafi

Teregulov and Muslim Magomayev. Around 1913-14. Left: Huseingulu Sarabski, Uzeyir Hajibeyov, Hanafi

Teregulov and Muslim Magomayev. Around 1913-14.

Local newspapers wrote:

"We need contemporary, cultured opera to serve as a vehicle

to educate the working masses since the existing Azerbaijani

opera does not meet such criteria. What kind of relationship

can exist between a socialist culture and the Hajibeyov's musical

comedy "Arshin Mal Alan" (The premiere of "Arshin Mal

Alan" (Cloth Peddler) by Uzeyir Hajibeyov took place

in 1913.

The story line is about a wealthy

merchant desirous of seeing his merchandise before purchasing.

Specifically, it meant that he wanted, at least, to have seen

a glimpse of his future bride before deciding to marry her. In

the early 20th century in Azerbaijan, tradition required that

women be veiled. In reality, the comedy is a satire against repressive

attitudes towards women in a traditional society) written in

the times of Noah which depicts the life of wealthy merchants

and landlords?" Their biased ideology concluded that "Uzeyir

Hajibeyov and Muslim Magomayev were products of the bourgeois

world."

As for the tar, according to Minister Guliyev, it "used

to be popular at a time when it served the tastes of the elite

circles of music. The masses did not need such a sophisticated

instrument at all. As such, the tar does not - and cannot - have

a future."

Heated arguments were not confined to intel lectuals. Mugham

operas, such as Hajibeyov's "Leyli and Majnun" were

excluded from the repertoire of the Azerbaijan Opera and Ballet

Theater. Tars were publicly burned and broken. Some people were

even afraid to keep them in their homes.

Incredible struggles were going on throughout the country, opposed

by Uzeyir Hajibeyov and other Azerbaijani intellectuals, including

such composers as Asaf Zeynalli (1909-1932) was the first

Azerbaijani composer ever to get a professional music education

in Azerbaijan. He graduated from the Azerbaijan State Conservatory

(now Baku Music Academy).

Though he was very young when he died, he was extremely active

and succeeded in introducing several music genres in Azerbaijan

for the first time including the first national romance and the

first symphonic music. His "Children's Suite" paved

the way for further development of Azerbaijani music for children.

Zeynalli was also very active in transcribing Azerbaijani folk

songs) and Afrasiyab Badalbeyli(Afrasiyab Badalbeyli (1907-1976)

is best remembered for having composed "Maiden's Tower",

the first ballet in Azerbaijan (1940) who helped to defend

the cultural heritage of the nation.

Such were the first intrusions of Soviet ideology into music

matters. Fortunately, they didn't last long. The tar and mugham

opera were returned to the musical life in Azerbaijan by the

early 1930s. However, the next decade brought little hope for

optimism.

Era of Repressions -1930s Era of Repressions -1930s

Left: Khadija Gayibova (1893-1938) with hand

on face. She was also an extremely active administrator and became

the Founder of Courses on Eastern Music (Eastern Conservatory).

She also made herself vulnerable by advocating strong ideas regarding

the further development of Azerbaijani music along an "Eastern

stream" with the establishment of an Eastern Conservatory

in the early 1920s. Such tendencies could easily be interpreted

as nationalistic, which were clearly forbidden. Gayibova was

arrested during the purges of 1937-38 and sentenced to 10 years

of hard labor. For some unknown reason, however, she was executed

in the NKVD prison.

The horror of Stalinist repression gripped the country in the

1930s, when tens of thousands of Azerbaijanis-including scientists,

writers, poets, artists, religious leaders, engineers, military

officials, government and even Communist Party officials-were

arrested.

Typically, they were ostracized from society because the government

branded them as "Enemies of the People" and threatened

anybody who befriended them with the same treatment.

"Trials" were usually carried out in the presence of

a "troika" (trio) of three representatives of NKVD

(Narodnyi Kommissariat Vnutrennikh Del-forerunner of the KGB)

and usually lasted less than 15 to 20 minutes. Rarely was there

any defense offered for the accused person. Rarely, was the accused

person even present. Hundreds of people were arrested each day,

many to be executed, exiled or sent to labor camps in Siberia.

Many died of hunger or from the severe cold climatic conditions.

Credit belongs to Farah Aliyeva for being the first musicologist

to delve into the issue of Stalin's repressions in Azerbaijani

music. (See "XX Asr Azerbaijan Musigisi - Totalitar Zaman

Kasiyinda" (20th Century Azerbaijani Music at the Crossroads

during the Totalitarian Era) in Musigi Dunyasi, No. 3-4 (17),

2003: pages 13-33.)

|

|

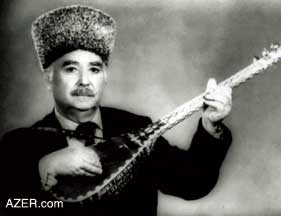

Above: (Left) Mikayil Azafli (1924-78), one

of Azerbaijan's prominent ashugs, was arrested in 1938, at the

age of 14 for accidentally spilling ink on Stalin's portrait

during a drawing lesson at school. Azafli was immediately taken

to the NKVD. As he knew the prison layout, he was able to escape,

although later he was captured and arrested two more times -1941

and 1945-46 - for the same "crime".

(Right): Minister of Culture Mustafa Guliyev, an arduous apologist

for the Russification of Azerbaijani music involved politicians,

journalists, writers and musicians in his attacks against tar

and mugham opera. His criticism of the contemporary state of

Azerbaijani music suddenly came to be interpreted as an underestimation

of the benefits of the Socialist epoch. He was arrested in 1938

and executed shortly afterwards, sharing the fate of those whom

he had attacked earlier.

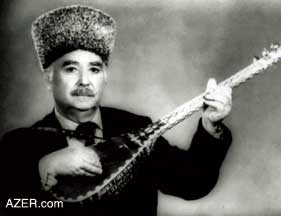

Left: Mammadkhan Bakikhanov and (Below):

Ahmad Bakikhanov, brothers who were distinguished as professional

tar players. (Ahmad was the father of composer Tofig Bakikhanov).

As the Bakikhanov family had Iranian roots, they chose to perform

Iranian mughams, which was interpreted as a sign of pro-Iranian

political orientation and their involvement in spying for Iran.

The brothers both spent nearly a year in prison and were released

only when composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov pleaded with Mir Jafar Baghirov,

head of the Communist Party in Azerbaijan, to free these these

musicians. Left: Mammadkhan Bakikhanov and (Below):

Ahmad Bakikhanov, brothers who were distinguished as professional

tar players. (Ahmad was the father of composer Tofig Bakikhanov).

As the Bakikhanov family had Iranian roots, they chose to perform

Iranian mughams, which was interpreted as a sign of pro-Iranian

political orientation and their involvement in spying for Iran.

The brothers both spent nearly a year in prison and were released

only when composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov pleaded with Mir Jafar Baghirov,

head of the Communist Party in Azerbaijan, to free these these

musicians.

Photos from the KGB

archives, which have recently been published, lay bare the horrors

of that epoch even more vividly than the texts of what transpired

during those interrogations. Despair, confusion and pain are

written across the faces of these innocent victims, exposing

the tortures and humiliation, which they suffered.

Those arrested were charged with various behaviors that were

considered to be crimes including anti-Soviet activities, pan-Turkism,

pan-Islamism, or spying for foreign intelligence services.

The true reasons why they were targeted could usually be traced

to family wealth, anti-Russian or anti-Communist activities during

the pre-Soviet era, having relatives who were living abroad;

befriending foreigners, or carrying out professional activities,

which somehow challenged communist ideology. Even the slightest

sentiment that countered

Soviet

ideology expressed privately, even through humor, could land

one in prison. Sometimes, people were vilified purely out of

personal revenge, as has come to light in regard to some of the

high-ranking officials, such as Mir Jafar Baghirov, who had been

appointed as Azerbaijan's First Secretary of the Communist Party

and served as Stalin's right hand. Soviet

ideology expressed privately, even through humor, could land

one in prison. Sometimes, people were vilified purely out of

personal revenge, as has come to light in regard to some of the

high-ranking officials, such as Mir Jafar Baghirov, who had been

appointed as Azerbaijan's First Secretary of the Communist Party

and served as Stalin's right hand.

Gallery of sadness

Almost all these criminal activities listed above could have

been used as an excuse to arrest pianist Khadija Gayibova (1893-1938).

She was also an extremely active administrator and became the

Founder of Courses on Eastern Music (Eastern Conservatory) as

well as the Music and Drama Studio for Turkic Women.

She also chaired the Department of Eastern Music of Narkompros

(Narodnyi Komissariat Prosvesheniia in Russian, which means "People's

Commissariat of Enlightenment").

Gayibova was born into the Muftizade family, members of which

held high Muslim clerical ranks. She later married Gayibzade,

the son of the Head of All Muslims of Southern Caucasus.

Her brother Mammad Muftizade was living in Turkey.

All these conditions were sufficient enough to get her arrested.

In addition, Gayibova made herself vulnerable by advocating strong

ideas regarding the further development of Azerbaijani music

along an "Eastern stream" with the establishment of

an Eastern Conservatory in the early 1920s. Such tendencies could

easily be interpreted as nationalistic, which were clearly forbidden.

As an open-minded, sociable person, Gayibova often held parties

and invited the music elite of Baku to her residence, including

Uzeyir Hajibeyov, Tarist Gurban Primov (1880-1965) and singer

Bulbul (1897-1961), as well as guest musicians, such as Reinhold

Gliere, Vladimir Gorovitz, Egon Petry and Nathan Milstein.

Musicians were not the only guests who frequented Gayibova's

home. In 1918-1920 prior to the Bolshevik takeover in Azerbaijan,

Musavat Party leaders were invited to her home, as were both

English and Turkish military officials who had come to Baku to

stave off the Russian invasion. Such associations turned out

to be fatal.

Gayibova was first arrested in 1933, but because of lack of evidence

of any criminal behavior, she was released. However, during the

repression years of 1937-1938, Gayibova was again arrested and

this time was sentenced to 10 years of hard labor. For some unknown

reason, however, she was shot in the NKVD prison. Those who shared

her prison cell said that Gayibova kept repeating in despair:

"I could have done so many things"(Gulrena Mirza, "Pervyie

zhenshiny-pianistki Azerbaijana" (Azerbaijan's first female

pianist), Azerbaijan IRS, no.4-5, 2000, 146).

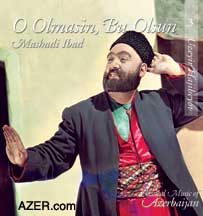

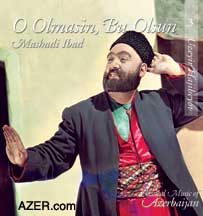

Left: Music Comedies by composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov,

such as "Mashadi Ibad" (featured here) and "Arshin

Mal Alan" (The Cloth Peddler), which were extremely popular

in the Pre-Revolutionary period (before 1920) were deemed during

the Soviet period to reflect bourgeois culture and were severely

criticized when, in fact, these works satirized many of the superficial

values and backwardness of the traditions of early 20th century

in Azerbaijan, particularly attitudes toward women, marriage,

education and religion. Left: Music Comedies by composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov,

such as "Mashadi Ibad" (featured here) and "Arshin

Mal Alan" (The Cloth Peddler), which were extremely popular

in the Pre-Revolutionary period (before 1920) were deemed during

the Soviet period to reflect bourgeois culture and were severely

criticized when, in fact, these works satirized many of the superficial

values and backwardness of the traditions of early 20th century

in Azerbaijan, particularly attitudes toward women, marriage,

education and religion.

Other musicians shared

the same fate. For example, Panfiliya Tanailidi (1892-1937),

an actress and singer who performed the major roles in some of

Hajibeyov's musical stage works, was eventually arrested for

"spying for Iran" and shot. Her tragic fate can be

traced to two situations: her close friendship with "Enemies

of the People", occasionally meeting an old friend and Iranian

citizen in Baku, and passing out Iranian cigarettes to friends

after touring there.

"Dangerous family links" was the excuse for arresting

Abbas Mirza Sharifzade (1893-1938). As Director of the Azerbaijan

Opera Theater, he staged most of the pre-Soviet Azerbaijani operas

and operettas and, indeed, played leading roles in many of them.

(Read about Sharifzade's arrest: "Reviving

the Memory of Silenced Voices: Actor Abbas Mirza Sharifzade"

by Azad Sharifov. AI 6.1 (Spring 1998).

His brother, Gulamreza Sharifzade was an active member of Musavat

Party and thus had fled Azerbaijan when the Bolsheviks came.

This was sufficient "evidence" to justify shooting

Abbas Mirza accusing him of anti-Soviet activities and spying

for Iran and Turkey.

Above: (From left to right): Singer Jahan Talishinskaya

(1909-1967) was related to a well-known scholar and Turkologist.

This association alone provided sufficient reason to not allow

her to participate at the "Decade of Azerbaijani Art and

Literature" in Moscow in 1938. She was later exiled to Kazakhstan.

Fortunately, she survived and returned to Azerbaijan after Stalin's

death in 1953.

Parviz Rustambeyov (1922-1949),

an outstanding Azerbaijani jazz musician, clarinetist and saxophonist,

was among the last innocent musicians of Stalin's terrible massacre.

Jazz music had always remained under strong suspicion during

the Soviet era.

Abbas Mirza Sharifzade (1893-1938),

Director of the Azerbaijan Opera Theater, was arrested for "dangerous

family links". He had staged most of the pre-Soviet Azerbaijani

operas and operettas and, often played the leading role. His

brother, Gulamreza Sharifzade had been an active member of Musavat

Party who organized the government during the short-lives Democratic

Republic of Azerbaijan (ADR) and thus had fled Azerbaijan when

the Bolsheviks came. This was sufficient "evidence"

to justify executing Sharifzade on charges of anti-Soviet activities

and spying for Iran and Turkey.

Singer Jahan Talishinskaya (1909-67) found herself in a similar

situation. Two family members had been accused of being "Enemies

of the People"-her sister and brother-in-law Khalid Said

Hojayev, who was a well-known scholar and Turkologist. This association

alone provided sufficient reason to pass over her and not allow

her to participate at the "Decade of Azerbaijani Art and

Literature" in Moscow in 1938. She was later exiled to Kazakhstan.

Fortunately, she survived and was able to return to Azerbaijan

after Stalin's death in 1953.

Outspokenness also sealed the fates of a number of musicians,

including Sergey Paniyev (1884-?) (According to F. Aliyeva,

the date of Paniyev's death has not been identified), who was

the Music Director of the Baku Russian Workers Theater as well

as the Chairman of the Union of Azerbaijani Composers. The KGB's

damning evidence against him included passing remarks he had

made, even about the cafeteria food: "Once we had lunch

in the canteen in Baksovet (Bakinskii Sovet, meaning Executive

Power of Baku or City Hall) with Paniyev. After mentioning the

very poor quality of the soup, Paniyev added that it seemed to

have been cooked according to the Party's program."(Farah

Aliyeva, "XX asr Azerbaijan musigisi," 20).

Another witness had testified: "In 1936, when discussing

the article in Pravda criticizing Shostakovich, (Shostakovich

was the main target for Stalin's 1948 campaign against "formalism"

in Soviet music. In fact, this was an attempt to isolate Soviet

music from the mainstream on 20th century music. Shostakovich

was dismissed from professorship at the Moscow Conservatory and

singled out. People were frightened to associate or even talk

to him). Paniyev expressed his frustration and anger, giving

rein to statements against the Party's main publishing body."

(Farah Aliyeva, "XX asr Azerbaijan musigisi," 20.)

Likewise, Mikayil Azafli (1924-78), one of Azerbaijan's prominent

ashugs, was arrested in 1938, at the age of 14 for spilling ink

accidentally on Stalin's portrait during a drawing lesson at

school. Azafli was immed12iately taken to the NKVD (Ali

Kafkasiyali in "Mikayil Azafli: Hayati, Sanati, Asarlari"

(Mikayil Azafli: Life, Career, Works) Erzurum: Eser Ofset, 1996).

As he knew the prison layout, he was able to escape, although

later he was captured and arrested two more times-1941 and 1945-46-for

the same "crime".

Playing the "wrong" type of music could also have dangerous

implications for those who dared it. The only fault of the two

distinguished Azerbaijani tar players, brothers Ahmad and Mammad

Bakikhanov, was that they chose to perform Iranian mughams. As

the Bakikhanov family had Iranian roots, this was interpreted

as a sign of pro-Iranian political orientation and, their involvement

in spying for this neighboring country. Both of these musicians

spent nearly a year in a jail and were released only when Uzeyir

Hajibeyov pleaded with Mir Jafar Baghirov to show mercy on these

outstanding musicians.

Predictably at a certain point, the repression engine began to

implode in upon itself and started to swallow its own executors.

This happened to Mustafa Guliyev, who had initiated campaigns

against the tar and mugham opera in the 1920s.

His criticism of the contemporary state of Azerbaijani music

suddenly came to be interpreted as an underestimation of the

benefits of the Socialist epoch. Arrested in 1938 and executed

shortly afterwards, Mustafa Guliyev shared the fate of those

whom he had attacked earlier.

The campaign against the "Enemies of the People" continued

until Stalin's death in 1953. Parviz Rustambeyov (1922-1949),

an outstanding Azerbaijani jazz musician, clarinetist and saxophonist,

was among the last innocent musicians of Stalin's terrible massacre.

Jazz music had always remained under strong suspicion during

the Soviet era. One of the famous Communist slogans of the Stalinist

era was: "Today, he is playing jazz; tomorrow, he will betray

the country!"

In 1944, Parviz was invited to join the orchestra of the famous

Polish jazz trumpeter Eddie Rosner (1910-1976)(Eddie Rosner

gained acclaim for his trumpet playing and ability to play two

trumpets at once. His career could have been in jeopardy as a

Jew after the invasion of Poland by the Nazis, but he fled to

the Soviet Union, which at that time embraced jazz. Hence, he

initially achieved an equally glowing reception in the USSR as

he had in France. Joseph Stalin even called to say he enjoyed

his performance for him. This led to his being made the head

of the Soviet Jazz Orchestra for a time. After the war this all

changed.

By 1946 Stalin became increasingly hostile to Jews and foreigners

and Rosner fell into disfavor and was sent to the Gulag prisons

on charges of treason with a 10-year sentence. He continued to

perform in the Gulag, however, and was allowed to use, or be

used, to lift the spirits of those interned. He was released

in 1953 after Stalin died. He returned to his native Berlin in

1973 and died there in poverty three years later [Wikipedia,

May 22, 2006]).This was the starting point for his enormous popularity

all over the Soviet Union. Some even referred to him as the "Soviet

Benny Goodman". Later Parviz established his own orchestra

and played in Baku cinemas. In January 1949, he was dismissed

for "worshipping the West," and in May 1949, he was

arrested. The official charge against him stated: "Parviz

Rustambeyov is an anti-Soviet and pro-American personality."

He was sentenced to 15 years of prison; however, on the day of

his trial, he died in his prison cell under highly suspicious

circumstances.

Azerbaijanis never stop lamenting about the innocent victims

of repressions. However, it is obvious that the losses that the

Azerbaijani culture experienced during those years could have

been much more catastrophic. The terror of the Stalinist period

could have touched many outstanding musicians of Azerbaijan,

such as the composer and conductor Niyazi, who maintained friendly

relations with many Azerbaijani intellectuals, who themselves

were later accused of being "Enemies of the People".

Niyazi's success at the "Decade of Azerbaijani Culture and

Art" in Moscow in 1938 when he conducted the opera "Nargiz"

by Muslim Magomayev stood him in good defense. As Nelli Alakbarova

reveals in her book about Niyazi: (Nelli Alakbarova in

"Jizn v muzyke" (The Life in Music) Moscow: Klassika,

2001). "Stalin turned to the people around him and

said: "Such a rare gift! Take care of this young man!"

Later, half-joking, half-seriously, Mir Jafar Baghirov used to

tease Niyazi: "If it weren't for Stalin's words, your bones

would have disintegrated long ago!"

"Censored!"

In the 1930s, during which time such a cruel repressive mechanism

was in high gear, the Soviets established an even more subtle-or,

perhaps, less visible-system of guiding art and culture. The

intense polemics where various viewpoints were expressed openly

in the media and in forums were gradually eliminated.

From then on, the substance of matters related to music were

discussed behind closed doors in the respective departments of

the Central Committee of the Communist Party, Ministry of Culture,

Union of Composers, Committee of the State Security (KGB), Committee

of the People's Control (Narodnyi Control) and the Main Department

on the Literature and Art Affairs (Glavlit).

All of these organizations were responsible for strict control

over all spheres of the cultural life in the country in terms

of their meeting the ideological agenda and criteria of "Socialist

Realism"-the main cultural doctrine of the Soviets.

Composers were required to get official approval for the lyrical

content of vocal music intended for the stage; otherwise, their

work would end up as a "dead project". Concert organizations

and media had to be cautious about the content of public performances.

Censorship penetrated all aspects of musical and cultural life

in the country.

This odd combination of social and aesthetical matters-"Socialist

Realism"-that defined the main tenets of Soviet cultural

doctrine was introduced in 1932. All Soviet art and literature

had to serve three criteria of this concept: (1) Party spirit

(partinost), (2) direct revelation of national roots (narodnost)

and (3) realism.

"Partinost" meant appraising Communist ideology and

the belief in a happy and prosperous future. "Narodnost"

required direct revelation of national roots, frequent use of

folk melodies, generally speaking, deriving music style from

folklore. "Realism" pointed at the necessity to feature

realistic images, rather than using metaphoric expressions that

might conceive political non-reliability.

Musicians, naturally, had more flexibility to maneuver within

this doctrine, due to the non-verbal nature of their art, especially

when they are compared to writers and graphic artists. Still,

this infamous triad formed the basis for composers, musicologists

and performers, as well as music critics. Despite how absurd

it may sound, even traditional and folk music had to meet the

criteria of "Socialist Realism". The past had to be

re-evaluated to serve the new ideology.

One of the most typical ways of applying partinost to composers'

works referred to slight modifying something that was well-known.

All Azerbaijani composers who wanted to write music based on

literary sources of the past were conscious of the necessity

of these "ideological injections". The opera Koroghlu

by Hajibeyov was among the first examples of this trend.

The doctrine of a Socialist Realism was verbalized in 1932, right

at the time when Hajibeyov began his work on Koroghlu. A frequent

motif emphasized the class struggle between the poor peasant

class and wealthy shahs and khans. This modification is clearly

seen when one compares Hajibeyov's version to another the same

legend as rendered by Turkish composer Adnan Saygun (1972). Saygun's

opera focuses on deep lyricism and psychological issues, whereas

Hajibeyov's work relates more to the heroic epic genre. Still,

Hajibeyov succeeded in creating high quality artistic work, and

nowadays the score composed for Koroghlu sounds as contemporary

as it did decades ago.

"Politically

correct" opera

The concept for Muslim Magomayev's (1885-1937) opera entitled

"Nargiz" became totally distorted due to the intrusion

of ideological matters. When the composer began writing the libretto,

he had a clear idea of the direction in which he wanted to develop

the story line. It would be a "love triangle" in the

spirit of old legends and folktales where two ill-fated young

lovers-Nargiz and Alyar-were separated by the wealthy landlord

Aghalarbey. But then politics interfered in quite an incredible

way: Nargiz and Alyar were identified as Communists, and Aghalarbey

became a member of the opposition-in this case, the Musavat Party.

At the end of the story, the youthful and innocent beauty Nargiz

was made to shoot two(!) antagonists: Aghalarbey and Bedal, another

Musavatist!

Such a corruption of the main character obviously spoiled the

entire narrative, given the fact that the initial version still

remained translucent under these artificialities. Logically,

even the musical development also happened to be stratified into

lyrical and political layers. Some episodes were clearly lyrical,

depicting the intense passion of the main characters. Other sections

of the opera are marked by abrupt and, often, illogical elaborations

based on didactic politics. Obviously, the lyrical parts dominated.

Some of the first reviewers of the opera's premiere mentioned

that the music didn't quite match the revolutionary plot, and

that the main characters were focused on love, rather than on

the social struggle.

The evidence of such crude interference in the creative process

can be discovered in the archives of composer Muslim Magomayev,

which I spent years researching at the Institute of Manuscripts

in Baku. The manuscripts of the libretto for his opera "Nargiz"

are covered with comments by Ali Ibrahimov, the Head of the Department

of Literature and Art in the Central Committee of the Communist

Party. It is obvious that Ibrahimov was not concerned about keeping

the originality of Magomayev's concept. His major concern was

to provide the ideological correctness of the plot.

For instance, the following critical remark was written in the

margin next to the love duet of Nargiz and Alyar: "replace

with an appeal to all the masses and develop on the revolutionary

theme". Nargiz' Aria in the First Act was marked: "Develop

a revolutionary spirit."

This was typical of the governmental censorship that Azerbaijani

and other Soviet composers faced throughout their careers, and

even much more after the Stalinist era (1953-1991). Enormous

creativity and enormous doses of diplomacy were needed to defend

a composer's initial concepts.

Even after Magomayev died in 1937, his opera suffered from experimentation,

both in regard to its content as well as its music style. For

example, a character named Jafar was introduced into the script.

He was a worker from Baku who arrived in the village to help

the peasants. Some people suggest that the name of this new character

was an attempt to flatter Mir Jafar Baghirov.

Ironically, after Stalin died and Mir Jafar was tried and executed,

having such a character in the opera accelerated the process

of causing "Nargiz" to be removed from the repertoire

of the Opera Theater. The situation in regard to "Nargiz"

is, indeed, tragic, since this opera is no longer part of the

national opera repertoire.

Magomayev's work definitely needs to be re-edited from its imposed

Soviet ideological clichés and returned to the stage-just

as two other music stage works have already been: the opera "Sevil"

by Fikrat Amirov and the ballet "Maiden's Tower" by

Afrasiyab Badalbeyli. In the late 1990s, two prominent musicians

of Azerbaijan, pianist Farhad Badalbeyli and composer Musa Mirzoyev,

carefully removed all obviously Soviet ideological injections

from the plots of both works, and now "Sevil" and "Maiden's

Tower" fully meet contemporary social realities. (Maiden's

Tower Ballet: New Plot Rids Soviet Propaganda, AI 7.4 (Winter

1999). Search at AZER.com).

Fate of traditional

music

One of the jokes that used to circulate was that the Soviet Union

was "a country with an unpredictable past". A set of

measures had been brought to life to reconcile artistic forms

of the past with requirements of the communist ideology. Some

forms of traditional and folk music were prohibited or severely

discriminated against, while others had only to be slightly modified

to align themselves with the dogmas of Socialist Realism.

Ashug (Ashugs are minstrels who accompany themselves on the traditional

stringed instrument saz. See "Music of the Bards: So

You Want to Become an Ashug" by Anna Oldfield Senarslan.

AI 12.4 (Winter 2004). Search AZER.com) music happened to be

one of the least problematic in this regard. This genre has always

been more connected to contemporary life, so that it had the

flexibility to reflect the new realities of the Soviet era. Beginning

immediately in the early 1920s, compositions were dedicated to

Lenin, Stalin, and Communism and, therefore, became an indispensable

part of ashug performances along with traditional epic sources.

This immediately earned ashugs the reputation of being somewhat

privileged among traditional musicians in the country. The Soviets

encouraged ashug performances and even established a form of

their assemblies to gather musicians from all regions of Azerbaijan.

The First Assembly of Azerbaijani Ashugs was held in Baku in

1936.

Meykhana is an improvised, rhythmic verbal poetic form, much

like the modern Western genre "rap". See "Meykhana:

Azerbaijan's Own Ancient Version of Rap Reappears" by Balasadig.

Meykhana and forms of religious music happened to be among

severely criticized forms of music. Meykhana, a kind of rhythmic

recitative poetry, performed mostly in Baku and nearby villages

contained many sensitive points in terms of the Soviets' ideological

agenda.

First of all, since Meykhana is improvisational by nature, this

horrified the regime which was totalitarian and sought control

of everything. That the improvisation related to verse, rather

than music, aggravated the situation and made it even more dangerous.

Its free literary content allowed the expression of any idea,

including anti-Soviet ones. This last characteristic was very

problematic as Meykhana, unlike mugham, focuses on routine everyday

life rather than sophisticated philosophical matters.

As such, Soviets labeled Meykhana as a "primitive"

genre, not worthy of being performed in public. However, during

World War II, Meykhana enjoyed a revival in the musical life

of Azerbaijanis as these verses generally helped people to cope

with dire times. In addition, many meykhanas were created against

Fascists and served to rally the soldiers. (This was mentioned

in the first ever book about "Meykhana" ever published

in Azerbaijan: Aytaj Rahimova, Azerbaijan musigisinda meykhana

janri (Genre of Meykhana in Azerbaijani Music) Baku: Nurlan,

2002, 3).

All forms of religious music were totally forbidden, particularly

"Shabih", which is a religious mystery about sufferings

of Imam Husein. This was crude invasion into objective processes,

since shabih had caused serious impact on the art music tradition

in the country, particularly, in relationship to the concept

of mugham opera. The first ever opera in Azerbaijan, "Leyli and Majnun"

by Uzeyir Hajibeyov contains many features of shabikh, first

of all, in the way of using choruses.

An anti-religious campaign was launched in relationship to the

traditional music of Azerbaijan. The lyrics of mughams, songs

and ashug's dastans were carefully censored to prevent manifestation

of religious feelings.

Dastans (traditional epic compositions), which had been created

to describe the Prophet Mohammad, were totally excluded from

ashugs' repertoire. Gazals (poetic verses) appealing to Allah

were prohibited as literary sources for mugham. The word "Allah"

was replaced with neutral terms or even politicized statements

in the lyrics of folk songs as well. For example, in the familiar

folksong called "Bari Bakh", the traditional appeal

to "Allah" has been substituted in the Soviet version

with "People".

Ay, Bari Bakh (Hey, Look at Me!)

(Folk version)

If you are allowed to marry me,

Hey, look at me, look at me,

Allah will like it, too,

Hey look at me, look at me.

Sani mana versalar,

Ay bari bakh, bari bakh,

Allaha da khosh galar

Ay bari bakh, bari bakh.

(Censored version during Soviet times)

If you are allowed to marry me,

Hey, look at me, look at me,

People will like it.

Hey, look at me, look at me

Sani mana versalar,

Ay bari bakh, bari bakh,

El-obaya khosh galar

Ay bari bakh, bari bakh.

These severe storms related to Soviet cultural policy bypassed

the traditional genre of mugham- Azerbaijan's treasure trove

of musical tradition that dates back centuries. This was, indeed,

an astounding and still is an inconceivable fact. The only possible

reason was that the Soviets hesitated to take on radical measures

towards this genre, which was held in such high regard in society

and was dearly loved by the people.

However, certain decisions were undertaken that changed the nature

of the content of Azerbaijani mugham. For instance, performers

were required to focus on Soviet literary sources such as the

verses of Aliagha Vahid, Samad Vurghun, Suleyman Rustam, and

later Bahtiyar Vahabzade, or Islam Safarli, rather than the classical

gazals of the 12th-19th centuries, which had been written by

Nizami, Fuzuli, Nasimi, and the poetess Natavan.

What also disturbed the Soviets about mugham (According

to Hajibeyov, each of seven major Azerbaijani mughams induces

certain mood. For instance, Rast creates a feeling of courage

and cheerfulness, Shur causes a joyful lyrical mood, Segah is

associated with love, Chahargah induced excitement and expressiveness,

Bayati Shiraz is melancholic, Shushtar is sad, and Humayun is

mournful.

Although, the number of distinct mughams is much larger, however,

all of them are somehow related to any of these seven families)

was its use of typical motifs of sadness and melancholy. As such,

mughams distinguished by optimism and courage, such as Heyrati

or Simayi Shams were immediately elevated to the top of traditional

music hierarchy in the Soviet Azerbaijan. Conversely, mughams,

which were said to evoke sad feelings, were more or less vetoed,

such as Shushtar, Khumayun, Rahab, Choban Bayati, Zamin Khara,

Mahur, or Kasma Shikasta.

Sega and other similar-sounding mughams were prohibited during

World War II as they were sad to induce feelings of sadness,

which were considered to be inappropriate at that time. This

policy continued throughout the Soviet period of music history

of Azerbaijan. This "Segregation Law" resulted in an

imbalanced development of the art of mugham in the Soviet Azerbaijan.

Performers more often elaborated on cheerful mughams, so that

music-wise they are now on a more advanced level if we compare

them to the Mugham of a century ago. However, Azerbaijani mughams,

which expressed a sadder, gloomier atmosphere both in regard

to intonation and structure wise, remain on the same relatively

simpler level that they had been during the early 1920s.

Despite all these hardships, most of genres of traditional music

that were outlawed during the Soviet period did not die out,

but continued to exist in the Soviet Azerbaijan. There was never

a time that Meykhanas were not performed in the Baku region.

And despite the fact that mughams were discouraged from time

to time, they were being performed within narrow circles of music

lovers.

However, it is obvious that natural processes in the development

of traditional music have been distorted. Negative consequences

of this process are still being felt.

History cannot be rewritten. All these stories and struggles

comprise the history of Azerbaijani music and culture. But thanks

to the courage and strength of some of our illustrious musicians

and composers, our music today still maintains its deep links

to our cultural heritage of the past.

See HAJIBEYOV.com (a Website

created by Azerbaijan International Magazine "to celebrate

the legacy of Azerbaijan's Great Composer Uzeyir Hajibeyov (1885-1948)".

_____________

Other articles by Aida Huseinova

Search at AZER.com.

(1) "Shostakovich's

Tenth Symphony - The Azerbaijani Link: Elmira Nazirova",

AI 11.1 (Spring 2003).

(2) "Gara

Garayev's 85th Jubilee", AI 11.1 (Spring 2003).

(3) "Arif

Malikov, Composer - Symphonic Music Built Upon Legend and

Imagination"(Interview with Aida Huseinova), AI 13.1 (Spring

2005).

(4) "Celebrating 75 Years: Lutfiyar

Imanov Reminisces about His Opera Career", AI 11.2 (Summer

2003).

(5) "Agshin

Alizade - New Ballet: Journey to the Caucasus". Published

in AI 10.4 (Winter 2002).

(6) "Muslim

Magomayev Celebrates 60th Jubilee", AI 10.3 (Autumn

2002).

Back to Index

AI 14.2 (Summer 2006)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|