|

Spring 2006 (14.1)

pages

48-53

The Heartache of Separation

Too Many Springs, Too Many Winters

by

Ummugulsum Sadigzade and her children

What

could be dearer than letters, especially between those who are

forced to separated from the ones they love, in this case a mother

from her four children. As the years passed, they all began to

lose hope that they might ever see one another again and the

letters served to be even more of a lifeline. What

could be dearer than letters, especially between those who are

forced to separated from the ones they love, in this case a mother

from her four children. As the years passed, they all began to

lose hope that they might ever see one another again and the

letters served to be even more of a lifeline.

The correspondence which follows is between Ummugulsum Sadigzade

who in 1937 was arrested and six months later sentenced to a

prison camp and her four children: Ogtay, Jighatay, Toghrul and

Gumral. It was Ummugulsum's niece, Sayyara, 21, who came to the

family's rescue and took care of the children.

These letters give us quite thorough information about the circumstances

that both mother and children were trying to endure - in the

harsh conditions of prison camp in Mordova, Central Russia, and

the children living in the Old City, Baku, who were bereft of

mother and father at such critical ages of childhood.

Unfortunately, not all of the letters that Ummugulsum wrote over

the seven years that she was imprisoned have been kept. However,

she managed to preserve all the letters that she received. Gumral,

the youngest child and only daughter, remembers that when her

mother returned to Azerbaijan, she brought a bag with her. Inside

were some items that she had sewn herself, plus a few food items,

some sugar lumps, butter, a few boiled potatoes and cookies.

Ummugulsum, 37 |

Sayyara, 21 |

Ogtay, 16 |

Jighatay, 14 |

Toghrul, 11 |

Gumral, 5 |

Years later, after Ummugulsum's

death, the family discovered, quite unexpectedly, that their

mother had also brought those precious letters back with her.

They found them in the old house in the Old City wrapped in a

thick cloth and tucked them away in a corner of an old trunk.

The family had almost thrown them out accidentally. They were

all organized neatly in chronological order.

The

children's letters usually started out something like this: "Mom,

we received the letter you sent that we were waiting for so much.

You don't know how happy we were to receive it. Thank God, you're

safe and sound! We read your letter many times..." The

children's letters usually started out something like this: "Mom,

we received the letter you sent that we were waiting for so much.

You don't know how happy we were to receive it. Thank God, you're

safe and sound! We read your letter many times..."

But the Mother would write back with such passion and emotion:

"My dear children, I received your letter today. I kissed

it and pressed it to my chest. My hands were trembling when I

opened the envelope. It has been so long since I received any

letters from home. I started thinking bad things. I read your

letter in one breath."

Credit goes to Aydin Huseinzade (the late husband of Gumral Sadigzade)

for organizing these letters and publishing them in Azeri in

2005 in a volume entitled "The Poet of Independence - Ummugulsum."

The book includes 56 letters. Ulviyya Mammadova has translated

all the letters from Azeri. A representative sampling are included

here, selected and edited by Betty Blair. This is the first time

they are being published in English.

The Family Members

Ummugulsum

(19001944)

Ummugulsum (pronounced: oom-moo-gool-SOOM), mother of four, was

arrested November 11, 1937, four months after her husband writer

Seyid Husein was arrested and denounced as an "Enemy of

the People."

After being held in Bayil prison in Baku for six months, Ummugulsum

was sentenced on May 10, 1938, to eight years in prison and exiled

to Prison Camp No. 4 in the Yavas settlement of Temlag, which

was located in Mordova Republic in the Central Volga Region (500

km southeast of Moscow). Ummugulsum was released seven years

later (a year earlier than her sentence mandated) to return home

because she was so ill. As government policy did not allow former

prisoners to live in large metropolitan centers, she could only

stay in Baku for 24 hours before she had to leave. She took her

youngest daughter Gumral and moved to Shamakhi, northwest of

Baku. Ummugulsum died a few months later in 1944.

Seyid Husein

(1887-1938)

Seyid Husein (pronounced: seh-EED hoo-SEYN) was a writer and

husband of Ummugulsum. He was arrested on July 15, 1937, and

shot January 5, 1938. There were no letters or any form of communication

from him after his arrest. The family was not officially notified

of his death 18 years later in 1956. By then, his wife Ummugulsum

and son Jighatay had also died.

There is only an occasional reference to him in these letters,

but since he had been accused of being an "Enemy of the

People", the family was probably afraid to mention his name,

as they knew the censors would be reading all letters.

Sayyara (1916-2002)

Sayyara (pronounced: sigh-yah-RAH) was only 21 years old when

Ummugulsum was arrested. She was a niece to the Sadigzade family

but had officially been adopted into the family since they did

not have a daughter for many years. Had it not been for Sayyara,

the children (ages 5-16) would have been sent off to orphanages,

or worse yet, sent into exile where likely they would not have

survived.

In these letters, Sayyara calls Ummugulsum her "mother"

and signs herself as "daughter". The correspondence

reveals that she actually did view Ummugulsum as mentor and mother.

Her letters show incredible maturity for a person so young. They

resonate with reality though she tries to keep Ummugulsum from

worrying, especially during the early years of separation. The

children were eternally grateful to her sacrifice to them in

raising them.

Ummugulsum often urged Sayyara to watch out for her own life

as she was missing the prime years for her chances to get married

and start her own family (especially in an Eastern culture).

But Sayyara stood beside the children, convinced that no one

would take care and love them as she did. As a result, she missed

those years and didn't marry until she was 60 years. Sayyara

passed away in 2002 at the age 86. In those last years, she said:

"I have but one wish. I wish peace everywhere. I don't want

anyone to have to face the hardship of those repression years

that we did!"

Ogtay (1921-

)

Ogtay (pronounced: og-TIE) was the oldest of Ummugulsum's four

children. Today he is a well-known artist. When he was 16 years

old, his father was arrested. Then his mother was arrested shortly

afterwards. And three years later, he also was sent into exile

(not to the war front) as a "political prisoner" because

his father had been branded as an "Enemy of the People".

He was sent to a hard-labor camp in Altai, South Central Russia

for five years (1941-1946). Her returned to find Toghrul and

Gumral left from his family. His father, mother and one brother

had all died as victims of repression.

In these letters, Ogtay often comments about his budding career

as an artist. Fortunately, he could throw himself into art to

deal with the pain and hardship he had to bear. He also often

comments about the everyday difficulties, lack of money and long

queues for everyday necessities such as bread.

Jighatay

(1923-1947)

Jighatay (pronounced: ji-ga-TIE) was 14 when his parents were

arrested in 1937. Four years later in September 1942, he was

called up for military service, but instead, since he was the

son of an "Enemy of the People", he was sent to Dagestan

[north of Azerbaijan], to a worker battalion instead of to the

war front.

He became ill with typhus and tuberculosis that they released

him to return home. He died at age 24. Ummugulsum was particularly

fond of Jighatay who was physically weak but who, of all the

children, seemed to share a sensitive for poetry and literary

expression just as his mother did.

Toghrul (1926-1995)

Toghrul (pronounced: tohg-ROOL) was 11 years old when his Mother

was arrested. He grew up to become an artist. We have no samples

of letters from Toghrul here.

Gumral (1929-

)

Gumral (pronounced: goom-RAHL) was five years old when her Mother

was arrested and sent into exile. She is the family member primarily

responsible for compiling the letters and publishing about the

life of her mother and their family.

Gumral was so young when this tragedy befell her family that

she rarely wrote her mother. She told us that once she did write

that their cat had had kittens. "What else could a kid write

under those circumstances?" she said.

Letters of the

Sadigzade Family

in Mordova, Eastern Russia. It was nine months later in March

1939 before she was able to notify her family of her whereabouts

or her situation. Ummugulsum had always worried about her son

Jighatay, who was physically weak. She addressed her first letter

from prison to him. He was 15 years old at the time.

Above:

Samples of the letters that

Ummugulsum and her family exchanged while she was in prison in

Central Russia. Letters date back to the early 1940s.

My dear, lovely son Jighatay! Though I am in exile, I'm so happy

to take pen in hand and write a letter addressed to my Jighatay.

My Jighatay, I received information today about my children.

Don't think that I'm living apart from you. Every waking moment,

all my thoughts are pre-occupied with you. My thoughts are so

involved with each of you that I don't feel so far away from

you. I even dream of you at night.

Are

you writing any poetry? Have you been able to reclaim the house?

You have the right to demand the house. I'm short of paper. That's

why I'm not writing everybody's name. Say hello to everybody.

I'm thinking of you all. I love you all. Kissing you many times. Are

you writing any poetry? Have you been able to reclaim the house?

You have the right to demand the house. I'm short of paper. That's

why I'm not writing everybody's name. Say hello to everybody.

I'm thinking of you all. I love you all. Kissing you many times.

- Your Mom, forced

to live in a foreign country

(March 23, 1939).

My dear Mother, hello! We received

your letter dated June 6, 1939. It made us so happy. I cried

for hours from happiness. Dear Mom, all of our children are "A"

students.

Above:

sample of "triangular

letter" that was so commonly sent from prison because the

prisoners rarely had access to envelopes. This triangular letter

is from the collection of Ahmad Jafarzade who was imprisoned

at the labor camp in Kolyma (1953-56).

Ogtay graduated from the Technical Art School on June 26. He

got "excellent" marks on his diploma. His teachers

praised him so much. I went with him when he defended his diploma

work. We invited his friends over to our home afterwards. We

had tea together. It made me sad that you were not here at that

Moment.

Dear Mother, you ask about Gumral. Well, she passed to the fourth

grade as an "A" student. Gumral is almost as tall as

I am. She is always reading books. She's a very diligent girl.

I get great satisfaction in watching over her.

We are now truly a family. So far, neither Ogtay, nor any of

the other children have disobeyed me. I'm a little Mother now.

Ogtay wanted to go study in Moscow, but I didn't let him go because

I couldn't have lived without him. I would die of worry. It's

good that he also took our situation into consideration and didn't

protest.

They say there won't be any letter from father [Seyid Husein].

Everybody in the family is safe and sound. You haven't written

anything about when you're coming. Write a thorough letter.

My dear let it end,

Let these days end,

Imprisonment is an enormous grief,

Brave is the one who can bear it to the end.

- Kissing you many

times. Sayyara (July 3, 1939)

My dear Mother! You can congratulate

me: I'll get my identification card tomorrow. I've grown taller

as well. I'm now 1 meter and 79 centimeters, and weigh 53 kilos,

200 grams.

It's not only me who is growing. Everybody, everything is growing,

increasing, developing. The Baku that you left 476 days ago also

has grown older and developed. Inshallah [If God wills], you'll

see for yourself when you come back, and you'll be very happy.

We are doing very fine here. Don't worry about us. Hello from

everybody. Bye for now. Kissing you.

- Jighatay (September

1, 1939)

My dear Mother! It's been one

year, 10 months, and 15 days since we were separated from you.

So many things have happened during this period. I have been

a father, a Mother, a host as well as a maid to this family of

four, which has been destroyed. To carry all these responsibilities

is a very hard task for a 22 - year young girl. I'm fulfilling

these responsible with honor.

|

"Mom, I'll be turning

18 in five days. I can't believe that I've only seen 17 springs

and 17 winters...Deep inside my heart and soul, I've seen hundreds

of springs and winters."

- Jighatay Sadigzade,

who was 14 when his mother was arrested and sentenced to eight

years in prison

|

My dear, after you left, I heard some say that "you did

wrong by keeping the children here." These words pierced

like a bullet. I cried when I heard these words. I was like a

bird with broken wings. I couldn't find anybody with whom to

express what I felt. I couldn't find anybody with whom to share

my grief.

So I share all my difficulties, my grief, only with my tears.

My dear, these two years have made me grow old and I've lost

some weight.

- Sayyara (September

10, 1939)

Dear Mother! We're always waiting

for you. But you haven't written us when you're going to return.

We sent a letter to Moscow asking about your release. You should

also try to write if you can. You were asking when I'm going

to take a vacation.

My dear, I haven't taken any vacation since my school started

on September 1, 1936. Not even one day because the situation

is very difficult. Instead, I get paid for vacation days. One

of these days they may draft Ogtay into the army. If they take

him away, my situation will worsen. Now we console each other.

My dear, it's me again.

Pour it, let me drink it again

Life is slipping away, the day is gone,

I never will be young again.

- Sayyara (September

25, 1939)

My dear Mom! You asked me to

send you vitamins. Believe me, there is no any drug store left

that I haven't asked, but I couldn't find them anywhere. For

now, I'm sending you vitamins for children. Let me know if I

should send more.

- Sayyara (December

21, 1939)

My dear son, Ogtay! I'm very

calm now after I received the letter from you. The picture Sayyara

and Gumral took together brings some consolation. Every day I

set that picture up in front of me and talk with them.

- Your Mother (1939)

Mom, you want to know what I

think about Azar marrying at age 19. You can be sure about me:

I'm not going to get married for the next 10-15 years because

I have "children" that I still must take care of. I'm

not going to get married before I bring them up and educate them.

Don't worry about us. We're all fine.

- Ogtay (January 10, 1940)

My dear Mother, Hello! We are

the happiest people in the world today. First of all, we received

your letter after such a long time. Second, your letter revived

me and challenged me to try harder. My dear, be responsible and

strong in your work. Don't worry about us. God is merciful. We'll

meet again and forget about our sorrows. Grief is short.

My dear, we wrote another letter to Moscow on behalf of Gumral

and received an answer 10 days later. First, they called us to

the Azerbaijan People's Commissariat of Internal Affairs. They

asked your name, last name and father's name. They will tell

us the results in 5-6 days. I'll write you in detail in my next

letter. God is merciful. Maybe we'll get some good news.

- Your daughter

Sayyara (March 10, 1940)

Dear Mother, There's nothing

to buy in Baku. Sometimes you can get butter for 55 manats per

kilo. When they sell sugar, there are usually 18,000 people in

the queue. They've offered it only three times in the past two

months.

- Your son Ogtay

(March 14, 1940)

My dear Mom! We were so worried.

Three months passed since we heard from you. Thank God, we finally

got a letter (I think I made the mistake here and wrote "God".

As you know, I got offended with God a long time ago, but grandma

doesn't know anything about it. If she did, I would be in trouble)!

We have written a letter to Beria [Head of the Gulag Prison system.

Obviously, an attempt again to plead for the release of their

Mother] about your release. We'll know the answer on March 19.

- Jighatay (March

15, 1940)

My dear Sayyara! I received

the letter and the parcel you sent. I'm getting on slowly, though

there are some difficulties. In my last letter I wrote you that

I was getting very worried and nervous. I'm better now and working.

I always fulfill more than my work quota so I am often given

privileges.

You ask if I'm going to return home, sooner or later so you come

and visit me. That sounded so funny to me. I wouldn't have any

problems, if I could only know when I would be retuning. But

who will tell me this?

Such a meeting would be possible as I am Stakhanovist myself but I don't recommend that you come yet. First

of all, I'm far away from you. It's not just three or four hours,

it would take you three days to come here and it would be very

difficult for a girl like you. Only a brave man could do it.

I'm totally against your coming here in winter. Besides, who

knows if I would be here when you arrived, or if they would send

me somewhere else? We should wait for a while.

Note: [Aleksei

G. Stakhanov (1906-1977) was a miner in the Soviet Union and

made a Hero of Socialist Labor. In 1935 he became a celebrity

for exceeding his worker productivity by allegedly mining 102

tons of coal in 5 hours and 45 minutes (14 times his quota).

[Wikipedia]

The clothes you have sent for me are not very useful. Spend the

money on food instead. I'll let you know when I need clothes.

However, those woolen socks were exactly what I needed. I didn't

have any warm socks. The weather is already getting so cold.

I don't know why you aren't sending me dried figs, doshab [grape

syrup], notebooks, paper and pencil. Next time, send me photos

of me with my sister, Ogtay with Jighatay in his sailor suit,

Toghrul with Sabutay, and a childhood photo of Gumral. Also take

a good photo of the five of you together and send it to me.

Sayyara, I'm allowed to write only once a month. So you all should

not wait until you receive a letter from me. Each of you five

should write me, one by one, every day of the week. Have mercy

on me. I'm living on your letters.

- Ummugulsum (April

10, 1940)

Dear Mother, Everybody is fine.

I often dream about you. I dream that you're in Baku. I dream

about father as well. I dream that both of you have come back,

but that you are leaving us again. I feel very sad when I have

such dreams. It comforts me so much when I dream about you. It

makes me feel like I have been talking to you. But when I wake

up, I'm so sad.

- Your son Ogtay

(April 20, 1940)

Dear Mother, We wrote a letter

about your case. They told us that we would get an answer on

April 22. So we went there and they told us to come back again

in a month. Again, we are waiting.

Mom, I'll be turning 18 in five days. I can't believe that I've

only seen 17 springs and 17 winters. Deep inside my heart and

soul, I've seen hundreds of springs and winters. If today I feel

spring inside of me, then tomorrow it will be winter for me.

When I see something good, it's spring for me, and when I see

something bad, it's winter.

They say that a person who faces a lot of difficulties ages prematurely.

That means the springs and winters of that person are repeated

not just once a year, but many times and the soul grow old very

fast. A young person with an old soul means he's an old person.

I have seen so many things during my 17 years. The things that

have happened to me have changed my character completely. I've

been thinking a lot lately and discovered many things. I don't

know what philosophy is but to think a lot leads one to philosophy.

Lately, I have become a philosopher myself.

Three years ago, you knew me very well. You knew my soul, too.

But now my soul is not like it was before, it has changed a lot.

If I were the same as I was three years ago, I would probably

write a long and boring poem to you on the occasion of my 17th

birthday. Now I hate poems.

I've been sitting here since morning writing nonsense. I don't

even understand myself what I'm writing here. You may think that

I'm stupid. No, I'm not a stupid boy at all. Or you may think

that your son is bored and will go crazy in the end. No, I will

never go mad! God forbid! Now I congratulate myself on my 18th

birthday and wonder what my destiny will be for the next 365

days.

- Your son Jighatay

(May 1, 1940)

Dear Mom, I'm so bored with

this separation. I spend my days and nights longing for you.

Gumral got excellent marks on all her exams. She is a beautiful

11 - year old girl - honest and healthy. She's very clever. Ogtay

also is clever and smart, though he's a little lazy.

My dear, they've confiscated our summerhouse and sold it. My

dear, I get 450 manats for a month. It's not enough for us. I'm

also working at a second job whenever I get the chance. I go

to offices from morning to night. I don't like it. When I go

there, they think that I'm just a "go-for", which I

don't like. A teaching course will begin from June 25. I want

to take it. I'll study and work at the same time. What can we

do? Human beings are obliged to tolerate every situation. I have

worked without a vacation for three years. We should try as much

as we can.

- Kissing you, Sayyara

(May 31, 1940)

Dear Mom! There are usually

four or five happiest moments in a person's life. Yesterday,

I had one of them: we received a wonderful letter from you. You

can't imagine how happy I was when I read it. If you continue

to write such letters, I'll gain five kilos from excitement alone.

- Your eldest son,

Ogtay (June 11, 1940)

My dear Mother, hello! You say

that you can write only once a month. You're right, we should

write you more often. I'll ask the children to write you as well.

In your last letter you wrote about my getting married and starting

my own family. My dear, I would never leave your family of young

children without supervision and get married. I couldn't do that!

If I were so inclined, I would have done that two years ago.

I see that you care about me and are worried. I'll think about

these things after you return. Children need supervision until

they are 20-22 years old, even if they are well behaved and clever.

No other person would be able to love your children and care

for them as much as I do, especially Gumral. When I go to bed,

I sometimes think to myself: what would she do if something ever

happened to me? I'll breathe freely only after you return.

They say that they are releasing women earlier than men. I hope

that's true! We wait impatiently for your return.

- Your daughter

Sayyara (July 10, 1940)

My dear Mom! The market is better.

Sometimes there is sugar, butter and other things if you wait

in a very long queue.

If you don't go to Mardakan [a major town on Absheron Peninsula

not far from Baku] to buy bread at night under the escort of

the stars, then you'll go hungry. If we arrive by 5 a.m., we

can buy bread by 9 a.m. It's impossible to get tomatoes, eggplants,

watermelons, potatoes, eggs, milk, and yogurt because they are

sold like gold. Anyway, we live well. Don't worry about us.

If some of us take up the pen and write to you, while others

don't, then it's simply because of laziness. Don't spare paper,

pen or time. Scold us. Make us ashamed so we'll be more active.

Now the sun will go down and you won't be able to read the letters

in darkness because you don't have electricity and you'll have

to wait until tomorrow. And tomorrow, maybe you'll go to the

bathhouse. We're sending you a comb; don't use anybody else's

comb.

- Jighatay (August

11, 1940)

My dear Mother. We're fine,

don't worry about us. We're soon going to send you a parcel.

We couldn't send it yet because both Sayyara, and I haven't had

work. I wanted to go to Moscow to study this year, but I didn't

because of the hard situation of our family. We need to earn

some money but I'll try to go next year.

- Ogtay (September

20, 1940)

Dear Mom! Many things have changed

in Baku in these three years. The city doesn't look like the

old Baku anymore. There are many new, big, beautiful buildings

here. Presently, they are constructing a trolleybus line in Baku.

- Jighatay (November

5, 1940)

My dear children! It's been

so long since I received any letter or parcel from you. I have

written many times. That's why I'm very worried about you. Your

letters give me strength and life If you love me and want me

to feel myself good and want me to be healthy, write me very

often!

Ogtay and Jighatay! Each of you write separate letters to Moscow,

Beria! Explain your situation and indicate the amount of your

stipends and salaries in those letters. Write that your younger

sister and brothers need Mother care. Let Toghrul and Gumral

write, too, and explain how bad the situation is and ask them

to release me. Write the letters in Russian. Doctors advise me

to eat food with vitamins. Send me some dried fruit and fish

oil. Say hello to everybody.

Kissing you many times, your Mother who is always worried. (This

letter was written in Russian, not the usual Azeri. It is not

dated).

Ogtay! I received your letter.

You can't imagine how happy I was. You ask why I'm not writing

you. You've upset me. I think anyone would respond like me if

they had a son who didn't write his mother in prison. What does

it mean? I know very well that you're not the kind of son who

would forget his mother and father. But the truth is you have

acted as if you have forgotten me.

You're writing that there has been a misunderstanding. You think

that Sayyara and I are writing secret messages to each other

in the old script [Arabic].

My son, you can be sure that this is not the case. We don't have

any secrets between each other. I write in the old script simply

because I'm short of paper here and the Arabic script uses less

space than Cyrillic. I have so many things to tell you but I

have neither time nor paper to do that. We are trying to fulfill

our work quota ahead of schedule here.

Ogtay, the dawn and sunset here are so beautiful that I cannot

describe it. The sun creates such beautiful colors at dawn and

sunset. It is characteristic of this place. Artists come here

just to paint these beautiful scenes.

When you send me letters, always send me paper with it too. Write

me about Toghrul, Gumush in detail. How is Jighatay's health?

My heart is aching because of his illness. Bye for now. Kissing

you.

- Ummugulsum (November

15, 1940)

Dear Mother! You always ask

us for paper and envelopes but envelopes are difficult to get

here as well. Learn how to make a triangle envelope from paper.

- Jighatay (January

11, 1941)

My dear Mom, hello! It's March

8 - Women's Freedom Day [Now called International Women's Day

- March 8]. It would be so wonderful if you also were free! I'm

still in postgraduate school. I have to take the exam for candidacy.

It's difficult to study. On the one hand, there's the financial

situation of our family, on the other hand, my concerns and worries

don't allow me to concentrate. I don't understand anything that

I read. God help me!

- Kissing you, Sayyara

(March 7, 1941)

My dear son Jighatay! I've been

receiving letters from you very often lately. I'm so happy that

I don't know how to express my feelings. I'm like a blind person

whose sight has been restored by a doctor who didn't charge a

fee! I need your letters very much. Of course, there can be no

other wish for a Mother than to hear the voice and listen to

the words of her children through these letters.

- Your Mother (March

17, 1941)

My dear son! Jighatay, We go

to work at a factory outside of the "zone" (fence).

This is a great freedom for us. Everyday at 7 a.m., we walk along

a narrow path that we have dug out of this desert snow. We walk

very carefully on the ice. I have slipped and fallen so many

times. Then at 12 noon, we return to the zone again and work

until 8 o'clock at night.

Today, the temperature was -30C [- 22F], yet we went to work.

Our breath, our eyebrows and eyelashes were frozen in this clear,

dry weather. There is no fog on the horizon, no cloud in the

sky. The March sun, rising above the forest, spreads its rays

on snowy mountains. Smoke is coming out of the chimneys against

the dark forests, and white deserts. One cannot describe the

beauty and magnificence of this stark nature. I told myself that,

at least, I should write these things to Jighatay.

Soon the forests will shed their white gown and put on a green

shirt. Then we will be very happy! Jighatay, nature here is very

rich. Imagine! There are days with temperatures of 40C to

-45C [-40F to -49F]. There are also strong winds, blizzards,

and storms. There are nights without moon and stars. Your Mother

leaves work and walks out to the zone. The angry thunderstorms,

remind me of death. The snow freezes on eyebrows and eyelashes

and clogs up one's nose. It makes you think it is the final hour

of life, or even of the world. Words simply cannot describe this

place. Enough now. Good-bye. I kiss you, my dear and lovely son,

Jighatay.

- Your Mother (March

17, 1941)

"Dear Mom! You're asking

me to send my full size standing photo to you. Don't ask me to

send such a photo because you'll get frightened. I'm almost 2

meters tall. But I'm sending you my photo anyway, because you

asked me to do so..."

We got your letter but there was one thing that didn't make me

happy. You're worried about me. This is funny. Have we changed

roles?

- Jighatay (March

26, 1941)

My dear Mother, hello! We received

your letter but one thing you wrote didn't make me happy. You

say that you haven't seen anything good in life and that you

have not been successful. I think you're wrong to say this. You

should not call yourself "unsuccessful" for temporary

difficulties. But having children who are well behaved, educated

and honorable, including a quite well-known young artist as a

son, a young specialist who is a post-graduate student and all

"A" students while there no parents are beside them,

doesn't that mean that you're successful in life?

To tell you the truth, your answer worried me very much. It's

true that you're facing many difficulties there, we can't deny

that. You're thinking only of your freedom. It's true that this

is an enormous grief. But we're grieving as much as you are -

not less!

And then you're writing as if I'm a free person and can do whatever

I want. My dear, this is not true either. Only stupid, unconscious

and arrogant youth can do that because they think only of their

own happiness. But that's not me. First of all, I don't want

to ruin the dignity of my family just for my own selfish interests.

And, secondly, I'm not going to leave four children alone.

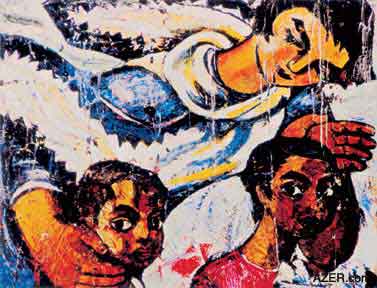

Above:

Art by Toghrul Narimanbeyov

(1930- ). His parents were also repressed. See more of Narimanbeyov's

works at AZgallery.org.

Don't think that we're living an easy life over here. It's true

that Ogtay and I are not little, but still he is a young boy.

He hasn't experienced life yet. He needs care himself. Besides,

I have to take care of the other children and educate them. So

if you won't be Mother to me, then who will be?

- Sayyara (April

21, 1941)

My dear and very respected Mother!

You cannot imagine how happy I was to receive a letter from you.

I was going crazy that day. My friends sensed something was going

on with me. They also got excited when they learned that I had

received a letter from you. Mom, the censors have scratched out

parts of your letter so much that I can't read them.

- Ogtay writing

to his Mother from prison camp (October 10, 1942)

Dear Mom! This is the eighth

letter that I've written to you but I haven't received anything

in return yet. This worries me so much. God forbid, I'm afraid

that something has happened to you. They've written me from home

and said that they haven't received anything from you either.

I'm so worried about you.

- Ogtay (February

27, 1943)

Mom, they drafted me in the

army in September 1942. We reached Khosta on December 16th. By

the 26th, they had sent my fellows to war and sent me to Sochi8

hospital. There I was treated for typhus until February 10. After

that, they transferred me to a therapeutic hospital. I came to

Baku in April because they have given me a month's leave to recuperate.

My dear Mom, you're writing that you cry at work every day. Why

are you doing this? You must tolerate. You have tolerated for

6.5 years, so tolerate for 1.5 years more.

- Jighatay (May

1, 1943)

My dear kind Mother! I understand

from your letters that you worry and think more about me than

the others. But I'm not a kid anymore. I'm a young man. I can

live independently no matter what the situation is. Mother, do

you know what date and what time it is now? Today is May 6th

at 11 o'clock. I'm turning 20 today. You're probably preparing

a gift for me. I'll always treasure that gift as a memory.

- Jighatay (May

1943)

My dear Mother! We've written

several letters requesting your release. You also should write.

God is merciful. Maybe they'll release you a year or two earlier.

I can't live without you any more. You won't recognize me if

you see me. I've grown very old. My hair is already turning gray.

My dear Mom, if you come, I'll live hundred years after that.

- Kissing you, Sayyara

(October 1, 1943)

Dear Sayyara, My dear, you're

writing that you are very worried and anxious. What can we do?

This is our fate. I know that they're not going to keep me here

until my sentence ends. They're releasing those who are invalid

and handicapped earlier. But the problem of transportation will

create an obstacle. I'm not working on night shift, as I'm a

handicap now. Send me some paper so I can write you. I've run

out of paper.

- Kissing you all,

your Mother (1943)

Dear Mom, I'm waiting for you

every minute, every second. All my life depends on you. I'm not

actually living now; my real life will start after you come back.

It's been already six years since we got separated from you.

It's not a joke. All five of us have lived without father and

Mother during these six years. It's very responsible task. They

have called me to so many offices because of you and interrogated

me. We have written to every place asking about your release

and we'll continue to write. You also write Everybody says hi

to you.

- Sayyara (November

11, 1943)

Dear Mom, This is the third

winter that I've spent in Siberia. I'm used to the severe weather

here. One can bear it if there is no wind. Snowy wind blows here

very often. I have warm clothes. Don't worry. Everything is fine.

I'm just concerned that you worry a lot about us. Mom, sometimes

I miss you so much here. I want to find somebody to talk with,

but I can't find anybody. I write a letter to you when I get

into trouble and I want to talk with you.

- Your son Ogtay

(December 25, 1943)

My dear Sayyara! i know that you'll be happy. I always imagine

your future family, your husband and children. I'm telling you

again, I'm warning you: get ready to get married! You should

get married as soon as I come back home. Start thinking about

it now...

- Your Mother (January

1, 1944)

Unfortunately that happy future

that Sayyara and the kids had been waiting so long and the days

the Mother lived in freedom and the days when children lived

with their Mother didn't last long, it lasted just four months...

Ummugulsum returned in June 1944. They didn't allow her to live

in Baku. She had to leave Baku for one of the regions of Azerbaijan

within 24 hours. She had to take her youngest child Gumral and

move to Shamakhi and rent a house there and live a difficult

life there.

The consequences of the difficult

life she had spent in exile in minus 35-40 degree cold began

then. She either had problem with her heart, or feet or had pains

in her stomach from the low quality food - peas, wheat and corn.

She passed away from a heart attack on one of those nights when

she was feeling bad. There was nobody dear next to her when she

closed her eyes eternally: 15-year old Gumral had left to go

find a doctor.

Back to Index AI 14.1 (Spring

2006)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|

The

children's letters usually started out something like this: "Mom,

we received the letter you sent that we were waiting for so much.

You don't know how happy we were to receive it. Thank God, you're

safe and sound! We read your letter many times..."

The

children's letters usually started out something like this: "Mom,

we received the letter you sent that we were waiting for so much.

You don't know how happy we were to receive it. Thank God, you're

safe and sound! We read your letter many times..."