|

Spring 2006 (14.1)

Pages

34-39

Ogtay Sadigzade

Targeting the Arts:

Son of an "Enemy of the People"

by

Ogtay Sadigzade

Ogtay Sadigzade (born 1921), distinguished

portrait artist, is one of very few Azerbaijanis who are still

alive today who survived imprisonment in Stalin's Gulag labor

camps. In 1941, at the age of 20, he was exiled to South Central

Russia for five years. His only crime: being the son of an "Enemy

of the People". Ogtay Sadigzade (born 1921), distinguished

portrait artist, is one of very few Azerbaijanis who are still

alive today who survived imprisonment in Stalin's Gulag labor

camps. In 1941, at the age of 20, he was exiled to South Central

Russia for five years. His only crime: being the son of an "Enemy

of the People".

But he wasn't the only member of his family to suffer. His father

Seyid Husein, a writer and member of Azerbaijan's intelligentsia,

was executed in 1938. His mother Ummugulsum was exiled for 7.5

years (1938-1945) and returned home so weak that she died shortly

afterwards. His brother Jighatay was sent into exile as a battalion

worker to Dagestan. He got tuberculosis and also we sent home

where he soon died at the age of 24.

Here Ogtay reflects on some of his experiences and how it shaped

his thought and art. See other articles in this issue related

to his mother Ummugulsum, which include several entries of her

prison diary, her poems, and letters to her children.

I was born in 1921 in Khizi, a village near Baku. My father and

mother, Seyid Husein (1887-1938) and Ummugulsum (1900-1944) had

just married when the Bolsheviks took control of Azerbaijan's

capital in April 1920. Since Father was a close relative of Mammad

Amin Rasulzade (Mammad Amin Rasulzade was the leader of the Musavat

Party, which established the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic (ADR)

in May 28, 1918.

The ADR collapsed after 23 months when the Bolsheviks took power

in Baku on April 28, 1920) who led the Musavat Party which was

in power when the Bolsheviks came, he feared for his life and

took mother and went into hiding in Khizi. Three months later,

father returned to Baku only to be arrested by the NKVD (NKVD:

(from Russian) Narodniy Komitet Vnutrennix Del, which means National

Committee for Internal Affairs. The NKVD became the forerunner

of the secret police agency of the KGB). They held him for two

months. It was the first of three times that he was arrested.

When he was arrested for the third time in 1937, I was 16 years

old. Actually, I wasn't home when it happened. I was in Novkhani,

one of Baku's suburbs at the "bagh" (Azeri for "summer

house") of Mammad Amin Rasulzade. They had just arrested

Rasulzade's son, Rasul, there. He was only 18 years old. So I

returned to the city to tell my family. Father was at our summer

house in Shuvalan, another suburb by the sea. At the time, he

was 50 years old. They said that they were taking him to some

meeting. My sister Gumral was five years old at the time but

she remembers that our brother Toghrul asked Father when he would

return. "The day after tomorrow", he had replied. At

first they believed him. Mother wasn't at home at the time. My

aunt, who was there with the children, started to cry and said

that he would never come back. She was right.

Left: Ogtay's classmates in fifth grade, 1932. Clockwise

(standing from left): Ogtay Sadigzade, Hajiagha Hasanzade, Aghareza

Hasanzade, Habib Habibzade and Ali Ahmadov. Left: Ogtay's classmates in fifth grade, 1932. Clockwise

(standing from left): Ogtay Sadigzade, Hajiagha Hasanzade, Aghareza

Hasanzade, Habib Habibzade and Ali Ahmadov.

I never saw my father

again. Two years later they told us that father had been given

a 10-year sentence but it wasn't true. It seems they had already

shot him, almost immediately after they arrested him although

we never learned the specific circumstances around his death.

In 1943 after the war had started, one of our family members

wrote a letter in Gumral's name to the NKVD and then they called

her there.

She was only in third grade at that time. They asked her what

she wanted. "Where's my father?" she asked. They told

her that she would get a letter from him after 1948. Imagine,

telling you to wait for five years before you would hear from

your father.

What could we do but wait? But the letter never came. It wasn't

until 1956 that we received his rehabilitation papers. There

they had written that he "died" on February 6, 1938,

not that he had been "executed".

I couldn't believe my father had been arrested. I thought there

must be some misunderstanding because he had never committed

a crime. He was a writer, critic, publicist, and educationist

- not a criminal. Not an "Enemy of the People," as

they claimed. But this was only the beginning of series of executions

of Azerbaijan's intelligentsia. Later on, they arrested other

major literary figures such as Mikayil Mushfig, Ahmad Javad,

Husein Javid, Boyukagha Nazarli and Taghi Shahbazi.

Mother's Arrest

And then four months later, they came after mother. We were afraid

that might happen as the agents had already come for some of

the wives of other prominent writers. So we made plans that my

aunt, Mammad Amin's wife, would come and stay with us in case

mother was taken. That way we four children wouldn't be left

alone. But before we could arrange anything, the NKVD arrested

my aunt and exiled her along with her entire family to Kazakhstan.

It was about midnight when the agents came for mother. Again

I was in shock. The state wanted to put us in an orphanage, but

Sayyara, our cousin, wouldn't let them. She came and took care

of us. She was 22 years old, only five years older than me, the

oldest child. Suddenly, her life was turned upside down and she

had the responsibility of taking care of us four children, ages

five to 16. Actually, even though Sayyara was our cousin, my

family had adopted her several years earlier because they wanted

a daughter, and Gumral had not yet been born.

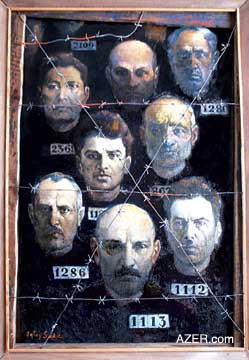

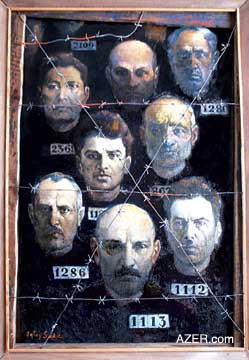

Left: Portraits of some of Azerbaijan's well-known writers

who were executed by Stalin. Clockwise from bottom center: Prisoner

No. 1113: Husein Javid (1882-1941); No. 1286: Seyid Husein, the

artist's father (1887-1937); No. 11??: Mikayil Mushfig (1908-1937);

No. 2369: Idris Akhundzade (dates unknown); No. 2109: Abbas Mirza

Sharifzade (1893-1938); No. 1280: Panah Gasimov (1881-1939);

No. 169. Yusif Vazir Chamanzaminly (1887-1943); and No. 1112:

Ahmad Javad (1892-1937). Portrait oil painting by Ogtay Sadigzade.

Ogtay and his mother Ummugulsum together spent 13 years in exile

in prison camps. Ogtay's father Seyid Husein was executed. This

painting is on display at the Husein Javid Home Museum, inside

Baku's Institute of Manuscripts. Left: Portraits of some of Azerbaijan's well-known writers

who were executed by Stalin. Clockwise from bottom center: Prisoner

No. 1113: Husein Javid (1882-1941); No. 1286: Seyid Husein, the

artist's father (1887-1937); No. 11??: Mikayil Mushfig (1908-1937);

No. 2369: Idris Akhundzade (dates unknown); No. 2109: Abbas Mirza

Sharifzade (1893-1938); No. 1280: Panah Gasimov (1881-1939);

No. 169. Yusif Vazir Chamanzaminly (1887-1943); and No. 1112:

Ahmad Javad (1892-1937). Portrait oil painting by Ogtay Sadigzade.

Ogtay and his mother Ummugulsum together spent 13 years in exile

in prison camps. Ogtay's father Seyid Husein was executed. This

painting is on display at the Husein Javid Home Museum, inside

Baku's Institute of Manuscripts.

So Sayyara knew us well as she had lived with us as a member

of the family. She felt that it was her duty to take care of

us. Under normal circumstances, she would have married and started

her own family during those years. She missed that chance and

didn't marry until she was in her 60s. She did her best for us

and tried to comfort my mother in prison and exile, promising

her that she would never leave us. What could she do? We have

always been eternally grateful to Sayyara for dedicating herself

to us in those difficult years.

After they took mother, I only saw her again - but just once.

They kept her in Bayil prison for a while. After several months,

she had visitation rights so we were able to go and visit her

one time for half an hour. I think it was in May. We waited outside

the prison for such a long time. There were so many people.

I remember the terrible stench. The smell was so bad. We met

with mother in the corridor. It was such a difficult moment for

us children and for her as well. Gumral, my little sister, was

only five years old. Mother couldn't recognize her because she

had lost so much weight. Of course, mother told us not to worry

about her and that she was fine. We also told that we were fine.

None of us could say what we really felt. How could we? What

could we do for each other when our hearts were so heavy? And

later when we wrote each other, it was much the same. We wrote

about general things. The letters were censored so we couldn't

write much. Naturally, we didn't want to worry each other.

I was very young back then - really just a child. We all kept

thinking that everything would be better soon. And then in 1941,

I myself was exiled as a son of an "Enemy of the People".

It would be five years before I returned home; but by then, mother

had already died at home in 1944.

Actually, my family didn't tell me about mother's death. It's

a practice in this part of the world not to disclose about someone's

death when you are alone and far away from your family. When

I returned from exile, I looked forward to seeing her. My family

had kept it a secret from me that she had died. I kept writing

letters to her, not knowing that she had already passed away.

Mother's death was the worst thing that ever happened in my life.

Nothing can be compared to the devastation that I felt when I

returned home from exile to find that only my younger brother

Toghrul and sister Gumral were all I had left. My father, mother

and brother were all dead.

My Own Arrest

Actually, when they came for me, it wasn't an arrest in the usual

sense of the word. World War II officially started for us in

the Soviet Union on June 21, 1941. On June 9, the NKVD [forerunner

of KGB] came for me. I was 20 years old at the time.

I received a notice to go to the army. I didn't go to the military

office; they came for me the next day. I was working at the Nizami

Museum of Literature at that time, showing some of my work. They

came and took me right in the middle of my evaluation - right

in the middle of the day. They told me that they were taking

me to the military service but I soon learned that they were

shipping me out to a hard labor camp. I was the son of an "Enemy

of the People". It didn't matter that they had already killed

my father and that they had already sent my mother to exile in

Central Asia.

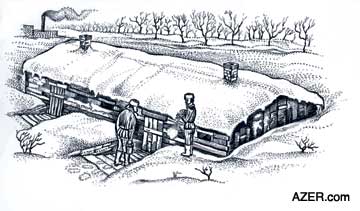

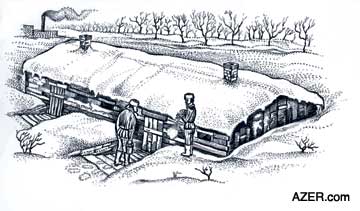

Left: This is a "zemlyanka - the barracks for prisoners

where Ogtay Sadigzade used to live while in exile in Altai, in

the North Arctic region. The buildings were built three feet

underground for warmth. Sketch by Ogtay Sadigzade, made especially

for this interview. Ogtay was exiled there for five years. The

conditions were so bad that he and some friends begged to go

to the war front, but were not allowed because they were "political

prisoners". Left: This is a "zemlyanka - the barracks for prisoners

where Ogtay Sadigzade used to live while in exile in Altai, in

the North Arctic region. The buildings were built three feet

underground for warmth. Sketch by Ogtay Sadigzade, made especially

for this interview. Ogtay was exiled there for five years. The

conditions were so bad that he and some friends begged to go

to the war front, but were not allowed because they were "political

prisoners".

They took me along with

others for a month and a half of military training. Then the

war started and everything changed. The Germans who were living

in the Caucasus around Shamkir and Khanlar in Azerbaijan were

exiled to Altay along with us. Later they were separated from

our group.

For the first three months, we stayed in Nasosniy Station near

Sumgayit, not far from Baku. We helped to build a military airport

runway. We had a difficult time. The food was adequate but the

working conditions were terrible.

There was no shade. We had to work all day under the blazing

sun. Our job was to crush stone and mix it with cement. We used

to work 18 hours a day - from the dawn to dusk.

After that, they sent us to Georgia, to Kabuleti near Batumi

for three months (September to November 1941). There we built

trenches so that tanks couldn't pass. At the end of November,

they sent us to Sochi [Georgia]. Again, we were assigned to digging

trenches.

Left: "Cosetta", an Illustration for Victor

Hugo's "Les Miserables" by Ogtay Sadigzade (1963).

On exhibit at the Azerbaijan State Museum of Art. Left: "Cosetta", an Illustration for Victor

Hugo's "Les Miserables" by Ogtay Sadigzade (1963).

On exhibit at the Azerbaijan State Museum of Art.

Then we returned to

the port of Baku, but I didn't have a chance to stop by home

to see my family. Little did I know that I would never see my

mother again. They shipped us out from there. We had no idea

where they were taking us. There were 5,000 of us on board that

ship. There was no place for so many people, so I was among those

who had to stay on deck in the midst of a snowstorm.

For the first time in my life, I could hardly keep myself from

crying. We had no idea where we were going or when we would be

back, or even whether we would be coming back at all. The ship

left Baku at night and arrived in Krasnovodsk (Today this city

is called Turkmenbashi. It is located on the Krasnovodsk Gulf

of the Caspian Sea, and its population is primarily ethnic Russian

and Azeri - Wikipedia: April 25, 2006) the next morning.

Then we were put on a train. Again I didn't know where we were

going. We were headed for the Garagum desert (The Karakum Desert,

also spelled Kara-Kum and Gara Gum ("Black Sand") is

a desert in Central Asia). Six or seven hours later, the train

stopped at the station. When I got out, I realized that there

was no end to the train. It was very long. Maybe, more than 1,000

people. Each wagon carried about 30-35 people. They had built

two levels of shelves in each of the wagons. That's where we

slept.

On our train, it was only men - young men from all over the Soviet

countries - Azerbaijanis, Armenians, Georgians, and there were

also Bulgarians, Hungarians and even some Greeks. There were

only a few Russians.

Eventually, we reached Tashkent (Tashkent is the current capital

of Uzbekistan). They let us bathe there. I wish they hadn't.

After leaving the bathhouse, I realized that I was full of lice.

It seems all the clothes were piled together and that's how my

clothes got infected. It was a situation which plagued me for

four years. I never could get rid of the lice.

Finally, we arrived in Rubsovsk, a provincial city in the Altay

region (Altay region is in South Central Russia) of South Central

Russia. When the war started [1941], the government had intended

to build a military plant here for producing tanks. But when

the war started tapering off, they decided to convert the factory

into manufacturing tractors instead. Everyone who had been exiled

to Rubsovsk took part in the construction of that plant.

We lived under very difficult conditions in "zemlyankas"

(Russian, for "underground huts"). These barracks were

mostly dug out underground. They were about three meters high

and housed 250 people. The walls were wooden, the floor was mud.

There were only two small windows. There was no heater and no

electricity. We used oil lamps. In the mornings, we would wake

up to find the walls inside covered with frost. The only telephone

in town was at the post office.

Lack of Food

As it was wartime, our greatest problem was lack of food. We

stayed hungry all the time. I constantly craved bread. Hunger

has a way of changing a person psychologically. When you're hungry,

you can think of nothing except food. You forget about all the

greater goals and principles that you have been taught. You are

consumed with only one thought - food. And even when we had enough

food, even when our stomachs were full, we were never satisfied.

They used to feed us potato skins. The actual potato itself was

sent to soldiers on the frontline. They used to make mashed potato

skins for us or baked pudding (he laughs). We had bread, too.

But what bread! It was impossible to eat. It looked more like

mud and tasted very sour. I have no idea what it was made of.

It was like glue. Sometimes, there was no choice but to eat it,

and I would get heartburn.

The

Soviets would ration the bread: 800 grams The

Soviets would ration the bread: 800 grams  forgood

workers who exceeded their quota, 500 grams for those who met

their quota, and only 300 grams if you didn't work. Usually,

we were given nothing more than bread. I got into the habit of

economizing. forgood

workers who exceeded their quota, 500 grams for those who met

their quota, and only 300 grams if you didn't work. Usually,

we were given nothing more than bread. I got into the habit of

economizing.

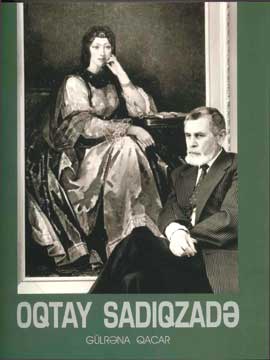

Right: Collection of Ogtay Sadigzade's works.

Text by Gulrana Gajar. 1984.

I would save a portion of bread from the morning for dinner in

the evening. In addition to bread, sometimes there was kasha

[plain boiled wheat]. But it doesn't take long to break the habit

of eating kasha [meaning it's not very tasty]. We were always

hungry.

Let me tell you a story about food. One day when I was returning

from work to the zemlyanka, I saw a Moldavian carrying some sugar

beets. He told me that about four to five kilometers from the

city there was a field of sugar beets. They used to harvest them

by digging them up and spreading them out on the ground during

cold weather. That would cause them to sweeten.

So one night, my friend and I took some sacks and went in search

of the sugar beets. It was the end of November. As we were going,

a strong wind blew up - they call such winds "buran"

(in Russian, it means "snowstorm" or "blizzard").

Those winds are so violent that you can barely stand up against

them. They hit you in the face and you can barely see anything.

After a long search, we finally located them. It was just a field

but there were sugar beets as far as you could see. We gathered

as many as we could - four sacks full. Then it got dark. As it

was desert and there were absolutely no landmarks, we didn't

know in which direction to start walking back. We walked for

a long time. Despite how windy and cold it was, we were sweating.

Then we started to get really worried that we might be lost and

we would freeze to death.

Then an idea crossed my mind. When we had headed out in search

of the field, the wind had been beating us from behind. Now that

we were returning, it was still behind us. So we figured we were

heading in the exact opposite direction that we should be.

We were so exhausted by the time we arrived back at the zemlyanka

early in the morning. I couldn't take a step further. But the

sugar beets saved us that winter. We would go and collect them

there from the desert. When you cook them, they taste much like

pumpkin: they're very sweet. Because of their high caloric value,

they saved us from starving. We continued to collect them for

a year and a half more. After that, they placed a guard there

in the field and we were afraid. Severe hunger continued until

1943. Towards the end of that year, America supplied us with

dried eggs, sugar cubes and other products.

Clothing

Clothing was also a problem. Because of the war, there was a

shortage of everything. We were given only trousers and a "telogreyka"

[Russian, meaning "body heater", meaning a thick cotton-padded

jacket]. Fortunately, the cotton padding did quite a good job

of staving off the cold. We wore it both in summer and winter.

Our shoes were made of thick felt. It kept our feet warm, but

whenever they got wet in winter, you were in real trouble. Your

feet would freeze. The climate was continental: very hot in summer

and very cold in winter.

Then in 1943, some aid came from America - some second hand clothes

and boots. I got a pair of boots and warm underwear. That was

good.

Bathing was also a problem. There was only one bathhouse in the

entire city. To bathe, we had to sign up in advance and go there

as a group. Can you imagine, we only got to bathe once every

three or four months. I remember that once our turn came at three

o'clock in the morning. And so we walked there - about three

kilometers distance. It was so cold, like -43 degrees Celsius

[-45 degrees Fahrenheit].

They used to try to sanitize our clothes against lice. They would

steam our clothes under high pressure. Sometimes they didn't

have enough pressure and our clothes would get soaked. We would

return to our barracks wearing wet clothes under our coats in

such extreme cold weather. Most people got sick. Even some of

the strong guys did. I'm surprised that I didn't because I've

never been especially strong. There were no doctors.

Usual Workday

At 6 o'clock, we had to wake up. Our work place was three kilometers

distance from the barracks. We had to be at work at 8 o'clock.

We would walk there; it would still be dark outside. Then we

would have lunch in the cafeteria at 12 noon. We would return

again for dinner at 7 o'clock at the same cafeteria after work.

We used to work 10 hours a day without a single day or weekend

off. There were no breaks until 1944.

In the beginning I had been involved at the factory digging the

hard ground, preparing the foundations of the building. I had

grown up as a "house kid". My parents had not allowed

me go outside much to play in the streets and alleys. After all,

keep in mind that it was in the early 1920s and life was quite

brutal and tumultuous back then. Physically, I wasn't very strong.

When I started working in the labor camp and assigned to digging

the ground, it was really hard for me. I couldn't even hold a

shovel. It was so hard to dig into that frozen ground. Gradually,

I got used to it. Those years Altai witnessed some of the coldest

temperatures in their history. The temperatures would go down

to -43C (-45F). It was extremely cold even for them.

After a while, I succeeded in finding another job. As I am an

artist, they were eager for me to work in that capacity. The

Soviet government could not live without painters. Their propaganda

was being carried out with the help of artists. There's no doubt

in my mind that art saved my life. After I started my new job,

my living conditions were very different. They even gave me a

studio. My job was to draw portraits of the leaders, make posters,

and political cartoons. It sure was a lot easier than digging.

Besides, I liked it.

Once I was commissioned to draw 40 different portraits of Stalin.

I had no other choice but to do it; otherwise, they would have

sent me to the military tribunal. Those were the days that if

you dared to slightly criticize Stalin, you could land in trouble.

I became so professional in drawing portraits of Stalin that

I could sketch him very quickly. I wasn't trying to express anything

about his personality. It just had to look like Stalin. For me,

it was like drawing a still life or a landscape, like drawing

from a template. We didn't have any paint so we could only use

two colors - red and black-red from women's lipstick and black

from mascara.

I had studied art at the art school in Baku named after Azim

Azimzade (Azim Azimzade was one of Azerbaijan's first professional

artists. He was famous for satirical sketches that exposed social

conditions, especially the wide gap that existed between the

rich and poor at the beginning of the 20th century) and then

I was sent into exile so I never got the chance to complete my

studies in Moscow or Leningrad. After I returned home from exile,

my family's financial situation prevented me from continuing

my education. Although I have received many titles and commissions,

I never received higher education.

The aim of my whole life has always been art. I never wanted

to be anything except an artist since I was a kid. The five years

that I lived in exile was a tremendous education for me in art.

My experiences in exile had a profound affect on the way my art

developed. Such experiences leave deep imprints even if one isn't

conscious of them, both enriching the human being psychologically

and broadening one's world vision. The artist needs to see many

things. The more he sees and experiences, the more his creativity

develops, especially portrait artists. Human characters have

always interested me.

Perhaps, I should have been a psychologist, instead of an artist.

In the camps you got to know so many different types of people

- both good and bad. I met thousands of people in exile. Everyone

had a different character, and everyone came from a different

world, a different reality. To be a portrait artist, you have

to be able to reveal the inner personality of a person. The eyes,

the movements of lips, shape of the face - they all reveal the

true inner nature of a person.

In addition to life in exile, I would say that my art developed

because of just plain hard work. Painting requires a lot of persistence

and determination. You have to work like a dog. It's 10 percent

talent and 90 percent hard work. Nothing is possible without

hard work.

Museums and classical books also shaped my art. If you want a

professional education in art, you have to read a lot. An artist

has to know something about everything. I read so many of the

Western classics while I was in exile; for example, Dickens,

Shakespeare, Balzac, Victor Hugo, and even some of the American

writers. They had a library in the camp and I read everything

I could get my hands on. Later I had the chance to visit a number

of European countries. There I visited many museums.

Only later in 1944 did they allow us to rent rooms in some of

the private apartments in town. That's when I began to work as

an artist and my living conditions started to improve.

|

"Stalin's repressions

(1920s to 1950s) were such an absurd period in our history -

not just in Azerbaijan, but the entire Soviet Union. The atrocities

that were committed can't even be compared to Hitler's. They

were much worse. Hitler went after his political enemies, but

Stalin destroyed his very own intelligentsia - the strength of

his nation."

--Ogtay Sadigzade,

Azerbaijani artist, who was exiled to a slave labor camp for

five years simply because he was the son of an writer

who had been falsely accused of being an "Enemy of the People"

|

I rented a room in the home of a woman, who lived with her daughter-in-law

and two grandchildren. For the rent, they preferred wood to heat

the place, not cash. To find wood was such a major problem for

them. At first when we arrived in Rubsovsk, the people were very

suspicious of us. They called us "Chyorniy Boyets"

(Russian for "Black Warriors") because we were dressed

in black.

The local population consisted mainly of women and children,

as all of the men had been sent off to war. After the camp authorities

allowed us to live in separate private houses, the attitude in

the community towards us totally changed and they grew to respect

us. When they got to know us personally, they realized that we

weren't bad people. They even tried to help us-most of us were

Azerbaijani, but there were Georgians, Armenians and prisoners

from other nations as well.

About 25-30 percent of the prisoners were former criminals -

some of them had committed serious crimes. The government sent

many of these "criminal prisoners" to the front, but

not ones like me, which they categorized as "political prisoners".

They considered us to be dangerous. We begged to be sent to the

war front rather than live the horrible life in the camps. There

was a commission to review every person's history but those who

had a parent whom they considered to be an "Enemy of the

People" were never sent to the war. They didn't trust us.

When it came to language, actually, Azeri was like an international

language there. There were so many Turkic-speaking people-Ajars

(Ajaria (also known as Ajara, Adjaria, Adjara, Adzharia and Adzhara)

is an Autonomous Republic of Georgia, in the southwestern corner

of the country, bordered by Turkey to the south and the eastern

end of the Black Sea - Wikipedia: March 30, 2006), Bessarabia

(Bessarabia or Bessarabiya (Basarabia in Romanian, Besarabya

in Turkish) was the name by which Imperial Russia designated

the eastern part of the principality of Moldavia annexed by Russia

in 1812. In 1918, Bessarabia declared its independence from Russia

and at the end of World War I, it united with the Kingdom of

Romania. The USSR annexed Bessarabia at the beginning of World

War II - Wikipedia: March 30, 2006), Tatars (Tatars is a collective

name applied to the Turkic people of Eastern Europe and Central

Asia. Before the 1920s, Russians used the name Tatar to designate

numerous peoples from the Azerbaijani Turks to tribes of the

Siberia. Tatars live in the central and southern parts of Russia

(the majority in Tatarstan), Ukraine, Poland and in Bulgaria,

China, Kazakhstan, Romania, Turkey and Uzbekistan.

They collectively numbered more than 10 million in the late 20th

century - Wikipedia, March 30, 2006) and Turkmen (Turkmen is

a name currently applied to two groups of Turkic peoples. The

ending of the name has no relation to the English words "man"

or "men". Historically, all of the Western or Oghuz

Turks have been called Türkmen or Turkoman, but nowadays

the term is usually restricted to two Western Turkic groups:

the Turkmen people of Turkmenistan and adjacent parts of Central

Asia, and the Turkmen people of northern Iraq - Wikipedia, March

30, 2006). Most of the Armenians could also speak Azeri, as did

Georgians. Of course, the local people spoke Russian, and it

was in exile that I learned Russian.

Writing Letters

I did write letters to my family but most of them have been lost.

The government didn't put any restrictions on how many letters

we could write. We could write as often as we wanted, but we

had to write in Russian; otherwise, the chances were slim that

the letters would get through. After all, they were censored.

It used to take about two months for letters to reach their destinations.

Those last three or four years when I was in exile, I used to

keep a diary, but I can't find it. I think it must be lost somewhere

in our place in Ichari Shahar [Old City] where my niece lives

now.

It's very important that the new generation realizes how difficult

it was back then. Only when you compare life today with life

back can you realize how easy it is now. I'm not saying that

there aren't a lot of difficulties today, but comparatively speaking,

it's much better now. People had so many problems during Soviet

period. Everything was a problem. So many things were not available.

One day you couldn't find meat. The next day, no sugar. We should

appreciate our life now no matter what problems we have to deal

with at the moment.

The Soviet system was a fraudulent system. Everything was based

on lies. Although our country has a lot of problems at the moment

I am hopeful that these problems will be solved in the near future.

There is still corruption and bribes, and nobody is taking measures

to prevent this. Financially, we are living better now than during

Soviet times. But there are still problems. Corruption should

be stopped.

Stalin

Excuse my language, but Stalin is the worst rascal of all. The

interesting point is that millions of people were so blind and

didn't realize it. People were like sheep. They believed in him;

they thought he was God. For example, my cousin Husniyya had

so much faith in him even though her family suffered so much.

When he died in 1953, she went crazy.

She couldn't believe that God could die. She went psycho. The

world turned upside down for her. She was nearly 50 years old

at that time. Husniyya could not believe what they said about

Stalin after his death. She was totally lost and didn't know

what to do for about two years.

So many people in my family suffered because of Stalin. My father

was killed, and my mother was arrested, my brother died in exile,

cousins were arrested and killed, my aunt's family and my uncle's

family were sent into exile, but still Husniyya was convinced

that these people were truly guilty.

No one was able to stop Stalin from doing all these evil things

because his organization was so strong. Nobody could counter

him. Ninety percent of those millions of people who were arrested

were totally innocent. There was no reason to arrest them. But

nobody dared to say anything because everything - the army, guns,

and power - were in his hands. The system was based on denouncing

others and spying on them. The system was so false; it had to

collapse in on itself - to implode. And that's exactly what happened.

The system rotted from inside.

But Mir Jafar Baghirov (Mir Jafar Baghirov was the First Secretary

of the Communist Party in Azerbaijan; in other words, "Stalin's

right hand man" in Azerbaijan) was even worse; he was a

vile person. At least Stalin had some principles; Mir Jafar did

not. He did things to oblige and please Stalin.

A few years ago, a film was made about Mir Jafar. It was a rather

amateurish thing. To tell you the truth, I didn't like it very

much. Several people were interviewed: some people criticized

him, while others praised him, insisting that he had many positive

sides. But it's not right to call him a good person just because

he gave some people apartments.

In the end, they showed footage of Baghirov's trial that took

place after Stalin's death. However, in general, the film depicts

Mir Jafar as a hero at the trial. He admitted to making mistakes

and said Armenians had deceived him but, in my opinion, he was

a totally corrupt person.

The film tries to show that Stalin wanted to deport all Azerbaijanis

to Central Asia, and that Mir Jafar persuaded him not to do it.

But consider how difficult it would have been to deport four

million people. Stalin would have had to recall half a million

soldiers from the army just to guard such a mass deportation.

Furthermore, where are the documents to prove such a deportation?

It's so important that our young people should feel responsible

to their own people and to the nation. The state is based upon

education, the army and the tax system. Without them, the state

could fall apart. These things are not strong in our country;

the youth should not be under any delusions. They should be conscious

and alert, and able to distinguish between what is good and what

is bad.

Stalin's repressions (1920s to 1950s) were such an absurd period

in our history - not just in Azerbaijan, but the entire Soviet

Union. The atrocities that were carried out can't even be compared

to Hitler's. They were a lot worse. Hitler went after his political

enemies, but Stalin destroyed his own intelligentsia.

It's impossible to compare Azerbaijan's intelligentsia of 1930s

and 1960s with the present day. We have declined in every sphere.

For us to reverse this trend would probably take at least two

generations. The problem is we don't have good teachers. To create

an intelligentsia, you need good teachers and you need to create

an environment in which intellectuals can flourish. At present,

these conditions don't exist: we neither have such teachers as

models, nor the cultural milieu to nurture and foster them.

Back to Index AI 14.1 (Spring

2006)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|

The

Soviets would ration the bread: 800 grams

The

Soviets would ration the bread: 800 grams