|

Spring 2006 (14.1)

Pages

24-25

Memoirs of 1937

Burning Our Books:

The Arabic Script Goes Up in Flames

by

Aziza Jafarzade

In an

attempt to consolidate power within the Soviet Union, Stalin

ordered that speakers of the Turkic languages - that is, Muslim

populations - must use the Cyrillic script and give up the Arabic

script that they had used for centuries. Even the Latin script,

which Azerbaijanis had officially adopted a decade earlier, was

forbidden. To enforce this decree, officials came around to towns

and villages and ordered that all books printed in Arabic script

were to be burned. The late Aziza Jafarzade (1921-2003) is haunted

by the memory of those days back in 1937. In an

attempt to consolidate power within the Soviet Union, Stalin

ordered that speakers of the Turkic languages - that is, Muslim

populations - must use the Cyrillic script and give up the Arabic

script that they had used for centuries. Even the Latin script,

which Azerbaijanis had officially adopted a decade earlier, was

forbidden. To enforce this decree, officials came around to towns

and villages and ordered that all books printed in Arabic script

were to be burned. The late Aziza Jafarzade (1921-2003) is haunted

by the memory of those days back in 1937.

Note that Georgia and Armenia, of Christian heritage, were allowed

to keep their ancient scripts. For more about the history of

alphabet changes in Azerbaijan, see "Alphabet and Language

in Transition", AI 8.1 (Spring 2000). Search at AZER.com.

"Executioner! The books that you

burned on bonfires Are the glory of thousands of minds And the

dreams of thousands of hearts! We leave this world, but they

remain as memory, So many feelings engraved on each page, They

are the glory of thousands of minds And the dreams of thousands

of hearts!" "Executioner! The books that you

burned on bonfires Are the glory of thousands of minds And the

dreams of thousands of hearts! We leave this world, but they

remain as memory, So many feelings engraved on each page, They

are the glory of thousands of minds And the dreams of thousands

of hearts!"

-Samad Vurghun "Burned Books"

We used to wake up every night

with nightmares and every morning we would get up - our young

hearts paralyzed with fear. We couldn't sleep well at night.

Our minds were filled with the images of the ashen faces of our

elders who, themselves, had not slept a wink throughout the night.

Their movements reminded us of ghosts and lifeless shadows. In

quiet whispers, they would say: "They took 'so and so' away

last night."

"And 'so and so' was also taken away towards morning,"

These realities were breaking our hearts. But when we would leave

our homes and go out on the streets to school, we couldn't sense

any of this. Everything was quiet. Few police were around and

you didn't see any "black cars" parked nearby.

Nor could you see any prisoners whose hands were cuffed behind

their backs and who, as we heard in tales "had fetters around

their necks." There was no evidence that anyone had been

taken away and imprisoned. No screams had been heard from the

houses where loved ones had been taken away. No one was crying

and sobbing or singing elegies . No one was even sighing out

loud for those who had been taken away. People were frightened.

Who could dare shed tears for an "Enemy of the People who

had betrayed the "Father of the Nation" ? Who could

dare criticize such a decision? It had been months since we had

heard that Javid was taken away, Mushfig was taken, too. And

Sanili, Ahmad Javad, Ruhulla Akhundov, and Husein Rahmanov.

It turned out that you couldn't even say the names of those who

had organized the Bolshevik Revolution, such as colleagues of

Lenin. Nor could you mention the name of Nariman Narimanov anymore.

Or read the books of those who had been taken away - not even

Narimanov's. So we didn't mention their names. We didn't read

their works. Children quickly forgot about their fears, too.

But we were no longer children; we were 15 years old.

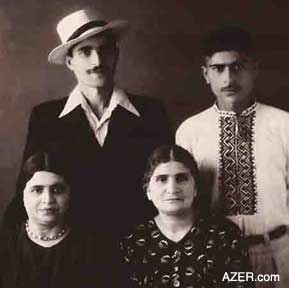

Left: Aziza Jafarzade (1921-2003) and her family in

the late 1940s before her brother Ahmad (1929-2000) was arrested

(1953) and sent into exile. Seated left to right: Aziza and her

mother Boyukkhanim. Standing Brothers Ahmad and Mahsun. Photo:

late 1940s. Left: Aziza Jafarzade (1921-2003) and her family in

the late 1940s before her brother Ahmad (1929-2000) was arrested

(1953) and sent into exile. Seated left to right: Aziza and her

mother Boyukkhanim. Standing Brothers Ahmad and Mahsun. Photo:

late 1940s.

On the one hand, we

had to be "heroic and loyal" just like Pavlik Morozov

whose "heroism and loyalty" was constantly praised.

Together with fellow Pioneers and Komsomols, we memorized "Lenin's

will" - advice that he offered upon his deathbed - which

was published in local newspapers. We pledged allegiance to be

loyal followers of the Party in the name of Communism. On the

other hand, whenever we would return to our homes, we were overwhelmed

with sorrows, whispers and secret tears.

The Novruz Holiday that March of 1937 will forever remain fixed

in my memory. Father had gone to the home of one of his friends

because he was afraid he would be arrested.

While we slept, my beloved mother had baked traditional Novruz

pastries - shakarburas and pakhlavas on a little stove known

as "burjuyka". She was the preserver of our most beautiful

ancient traditions. She was the treasury of our folk poetry.

On March 21st when the New Year was ushered in, she would close

all the doors and windows tight. She would then place a large

round copper tray in the middle of the room and arrange seven

different kinds of food, which had names starting with the letter

"S".

In the kitchen she would display the "samani" that

she had secretly grown beside the shakarbura and pakhlavas.

Then there was a sudden knock on our door. The color totally

drained from my mother's already pale face. She grabbed the candles

that she was getting ready to light and hid them among the blankets

that lay folded neatly in the corner of the room. There was one

candle for each of us children.

Then she covered the khoncha with my little brother's blanket.

She quickly opened the door. She knew not to be slow in order

not to arouse suspicion. After all, what could one possibly be

doing around the house to be so slow in opening the door?

Our neighbor Meyransa khanim , known as the "information

bureau" for our entire apartment complex, burst in. Despite

the fact that she was noisy and gossipy, she was a kind and gentle

person. She started asking my mother: "Hey girl, if you

have any books at home written by authors who have been repressed

, gather and burn them right away. They're threatening to search

every apartment. If they find any of those books, they'll arrest

the owner and take him away. Come on, get up, get going!"

She spoke as if my mother were sitting down. As if she weren't

standing there face-to-face with her. Then Meyransa khanim headed

straight for my bookshelf. She was sure that she was doing us

a favor. She shook my bookshelf.

Already those who had heard these rumors were building a bonfire

in the courtyard. And so, I had no choice but to haul away my

own books as well as those of my father's and throw them onto

the bonfire. What wretched hands.

Those dry pages quickly caught fire. What were they? Works of

the world's great poets such as Firdovsi who had written "Shahname".

Firdovsi had been branded as an "Enemy of the People".

Another was a translation by the poet Mikayil Mushfig. Another

, another edited by Ruhulla Akhundov, charged with being an "Enemy

of the People".

Others included Fuzuli who had always praised purity and love.

Then there was the rebellious Nasimi who had sacrificed his life

for human happiness. His book was included on the pile simply

because it had been published in the Arabic script. Sabir's passionate,

revolutionary satire in poetic verse, called "Hophop-name"

was burned simply because the foreword of the book had been written

by Seyid Husein who was charged with being an "Enemy of

the People. Also there were copies of the journal "Molla

Nasraddin" whose writers had struggled so much against intellectual

darkness.

My father had collected rare works from Central Asia and some

of the Middle Eastern countries, which he had visited after exerting

a great effort. With money he had saved from his meager salary

for daily provisions, and from his wife's dowry, father had bought

rare manuscripts, autographed divans, and works in various fields

of science. Most of them were kept in the village at the house

of my stepmother Kheyri Khankishi gizi.

"Hey girl, tell that poor woman as well so that she destroys

all of the mullah's writings belonging to your husband. Never

mind what she says, those books are harmful for children."

And so it was. The sons of our nation who had contributed immortal

works to universal thinking were blazing away in our courtyard.

And inside, my mother, who hardly ever dared to let me out of

her sight, was organizing to send me off to the village to my

stepmother's place. I knew what she was going through. But it

seems her fear had intensified even more since the order had

come to burn the books.

Strangely, the news had already reached the village even before

it had reached us - this village that had no telephones this

village, which could not be reached by car this village where

it took a week to receive a telegram because the postman had

to deliver it via donkey.

Kheyri Khankishi gizi, who was totally illiterate and considered

any book written in the Arabic script to be the holy Koran, had

not burned my father's valuable books. She didn't dare to burn

them. She simply had stuffed them into a niche in the wall. Then

she had taken some of the other books to the "Broken Pir"

.

Others, she had buried. She had even carried some of them on

her back to the edge of the Pirsaat River. "Not a single

paper belonging to my father was stored at home. The old lady

hugged me and she was crying and begging forgiveness from me

instead of her son - my father: "What was I to do, 'Light

of my Eye'? God forbid if they had found any Korans in our home.

There were so many people who spied on you. Then, my dear ones

would have been sent to those places where they show no mercy."

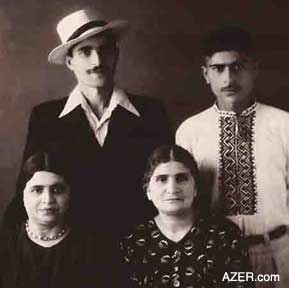

Below: Svetlana, 9, with Joseph Stalin her

father, 1935.

Father

had said it just like that: "they would send you" as

if we were some sort of package or piece of paper. What were

we? Father

had said it just like that: "they would send you" as

if we were some sort of package or piece of paper. What were

we?

Actually, Mother had acted more responsibly than we had. Those

books that were floating down the Pirsaat River were gone but,

at least, but later we found many pages that had not been damaged

among those that had rotted in the niche in the wall or that

had been gnawed upon by rats or the domestic animals at the "Broken

Pir". We could mend the torn pages. "God bless her

soul a thousand times, Kheyri Khankishi gizi. May her soul rest

in peace."

I went back and told my mother about the niche. Never again would

we return to this subject. My father passed away from grief that

same year.

I've experienced and lived through those times when the Arabic

script was cursed - this script that didn't belong just to our

nation alone, but to half of the world. This script that preserves

the works the great poet philosophers for mankind such as Firdovsi,

Nizami, Khagani, Ibn Sina, Navai, Jalaladdin Rumi, Nasiraddin

Tusi, An-Nasavi, Ibn Khaldun, Al-Mugaddasi, and Iban al-Asir

I've lived through those times that wiped out these literary

and philosophical giants from the history and culture of Azerbaijan

and other Central Asian nations with the words: "Enemy of

the People". I've lived through those times when the books

and manuscripts written in this alphabet were burned.

The ashes of this criminality - when we threw our Arabic script

books into the fires - still smolder in the soul of our nation.

Mardakan, May 16th, 1988, published

Published as "Yandirdigim kitablar" (The Books I Burned)

in Communist (newspaper), August 6, 1988. No. 253, p.3. Translated

from Azeri by Gulnar Aydamirova. Edited by Betty Blair.

Back to Index AI 14.1 (Spring

2006)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|