|

Spring 2004 (12.1)

Pages

30-33

Natig Rasulzade

Tram

(1991)

Tramvay

Natig Rasulzade was born in Baku on

June 5, 1949. In 1975, he graduated from the Literature Institute

in Moscow. Natig Rasulzade was born in Baku on

June 5, 1949. In 1975, he graduated from the Literature Institute

in Moscow.

He is the author of about 30 books, which have been published

in Baku, Moscow, Hungary, Poland and Yugoslavia. Among them such

books as Notes of a Person who Committed Suicide (Zapiski Samoubiytsi),

Rider in the Night (Vsadnik v Nochi), Nonsense, (Nonsens), Year

of Love (God Lyubvi), Rain on the Holiday (Dozhd v Prazdnik),

Among Ghosts (Sredi Prizrakov), I Draw a Bird (Risuyu Ptitsu),

Roads under the Stars (Dorogi pod Zvyozdami), and Person from

the Choir (Chelovek iz Khora).

He has written screenplays for numerous movies including: Don't

Believe Fairies (Ne Verte Feyam), Rain on the Holiday (Dozhd

v Prazdnik), Live, Gold Fish! (Jivi, Zolotaya Ribka!), Delusion

(Navazhdeniye), Person from the Choir (Chelovek iz Khora), Murder

on the Night Train (Ubiystvo v Nochnom Poyezde), Robbers (Grabiteli),

Outcast (Izgoy), Once Upon a Time There Lived a Cow (Zhila-Bila

Korova), Music Lessons (Uroki Muziki) and Wizard (Koldun). Together

with Eldar Guliyev, he has written: This Wonderful World (Etot

Prekrasniy Mir) and Sanatorium (Sanatoriy) and with Vagif Mustafayev,

the co-authored Monument (Pamyatnik).

In 1984, he received the GosTeleRadio (State TV and Radio) Award

for Best Play of the Year (1984) and the SSR Russian Ostrovsky

Award. He was recipient of Azerbaijan Komsomol Award (1988) and

Honored Art Worker (1999).

What is it like for a country

to transition from a different political and economic system

- as was the case when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 and

Azerbaijan gained its independence? Take a ride on Rasulzade's

Tram in the midst of an unrelenting blizzard for a perspective,

replete with symbolism, that's hard to forget.

Tram was translated from Russian

by Arzu Aghayeva and edited by Betty Blair. This is the first

time Rasulzade's works have been featured in Azerbaijan International.

An alternative spelling of his name via Russian is Natik Rasul-zade.

· · ·

We were still playing cards

long past midnight. The game had been so fascinating that I had

forgotten the time as I always do when playing Preference with

friends. My shoulders were numb and I stretched my head back

to work my neck muscles, which had become stiff. At that moment

the clock struck, drawing my attention to the large antique clock.

The hands were showing a quarter to one.

I was startled: could we really have been playing so long? I

had arrived there at six, immediately following my work. My friends

- a pleasant married couple whom I had known for more than 10

years - protested when I told them I must leave. In a tone that

allowed no room for objections, the hostess insisted on making

the sofa into a bed so I could sleep there in the living room.

I would get a good night's sleep, she promised, her voice softening

as she smiled kindly at me.

I thanked her and started preparing to go home, referring to

the fact that early the next morning someone would be coming

to my place on urgent business, and it was already too late to

cancel the appointment. So saying goodbye to my friends and to

our regular partner in card games - their neighbor who lived

on the same floor landing of the apartment - I left the hospitable

apartment and headed out into the street.

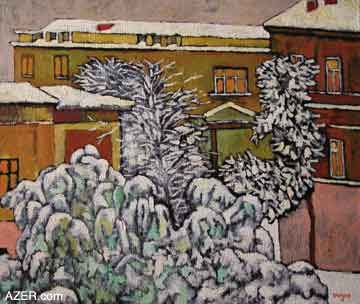

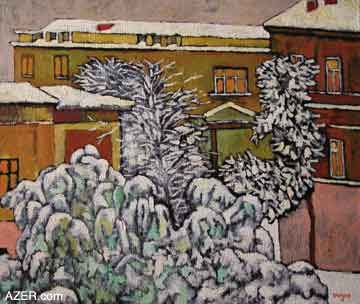

Art: Vugar Muradov. Visit AZgallery.org for contacts. Art: Vugar Muradov. Visit AZgallery.org for contacts.

A cold wind was blowing and it was snowing. It was quite chilly.

I hunched my head down into my shoulders, turned up the collar

of my overcoat, and began walking briskly through the snow, which

crunched under my feet. I knew deep down that there wasn't the

slightest chance of finding any transportation in the city that

would take me home.

Despite my pessimism, I had hardly walked 100 meters along the

tram rails down the middle of the street, when quite unexpectedly

a tram appeared. Its lights glowed invitingly and it stopped,

opening its doors almost in front of me. It turned out it to

be a regular tram stop - just one that I had never noticed before.

The well-lit tramcar looked quite inviting and cozy in the cold

dark night and that's why I didn't pay much attention to the

fact that this tram wouldn't be stopping very close to my home.

After the ride, I would still have to walk quite a distance on

foot.

Nevertheless, I had little choice. There was not a single taxi

in the streets and, even if there had been, it would have been

a rare taxi driver that would have agreed to take me to the upper

part of the city during such a snowfall.

I stepped up into the tram and glanced around. There were four

passengers sitting, dispersed throughout the train, here and

there. That, in itself, was a significant number given that it

was in the wee hours of the morning. This was the last tram,

and obviously after dropping us off, it would head for the depot.

Usually, on the final run, you rarely ever saw any passengers

- especially during wintertime. By about 10 o'clock in the evening

these last few years, the city was nearly dead. You almost saw

no one in the streets.

I sat down and for some time stared out through the window, watching

the blizzard. Not a thought crossed my mind. It felt so good

and cozy to be sitting next to the window in the lit tram, knowing

that soon I would be home and could lie down in a clean and warm

bed. I was eager for sleep. The rhythmic clanking of the tram

wheels, somewhat softened by the snow on the rails, lulled and

relaxed me. I didn't even notice that I had begun to nod and,

soon afterwards, fell into a deep sleep.

Suddenly, I was jarred awake. I sensed something foreboding and

uneasy. I opened my eyes, shook myself and looked around, unable

to figure out how long I had been sleeping. As before, there

were still the same four passengers sitting in the car. Behind

a dirty curtain that separated the passengers from the driver,

you could sense the presence of the tram driver. The tram had

stopped and, for some reason, it seemed to me that it had been

already standing for quite some time. I waited a moment to see

if it would start up again. When it didn't, I asked in a loud

voice: "What's the matter? Why are we stopped?"

The four men whom I had addressed in a rather general way only

stared at me. One of them made a limp gesture, waving his hand,

like he didn't care. Of course, it was understandable; nobody

wanted to talk. It was late. Everybody just wanted to sleep.

From behind the curtain of the cabin, a driver, with tousled

hair, looked out. His eyes immediately settled on me - the person

who had asked the question - and he announced in colorless voice:

"The rails are covered with snow. It's impossible to drive

through it."

"What do you mean?" I began to fret. "What are

you talking about? What do you mean 'we can't drive through it'?

What should we do then? We can't just sit here until morning."

Perplexed, I looked at the other passengers, hoping for some

compassion and support. They remained stone silent.

"Well, why 'til morning" the driver said lazily and

again slipped back behind the curtain. Judging by his speech

that suddenly became incoherent, it seemed he was chewing something.

After a short pause (it seems he must have finished chewing on

whatever it was), he added more distinctly. His words, as before,

were not very convincing.

"But if you want, I've got a shovel here." He became

silent for a while, puttering about. Then I heard a clinking

sound and he continued: "Even two. If you want, you can

clean the road. Then I could continue driving, little by little"

"Clean the road?" Perhaps, I had misunderstood him.

"What do you mean 'clean the road'?"

"And what's wrong with that?" he responded resentfully,

having detected from my voice that I had been offended. He kept

silent for some time and after a long pause, asked: "What

do you suggest? Nobody will do it for youOr else you can go on

foot."

"Indeed," I decided. "I'd rather go on foot."

I got up, glanced at the motionless figures of the four others

sitting there, and headed for the tram's front door. The driver

obligingly pulled the lever and the door opened. The cold air

rushed at me, burning me and jarred me awake. I headed out into

the night. The door immediately closed behind me.

ButMy God, what was this? I looked around in horror. Everywhere,

as far as the eye could see, stretched a dark steppe covered

with snow. Beyond, I could faintly make out a grove of trees

or forest. But it was impossible to distinguish any further details.

I stopped, rooted to the ground, still holding on to the handrail

of the tram as if afraid that if I let go, the tram would disappear

and I would be left alone in this vast dark expanse. The absurdity

of the tram going anywhere, sobered me a little, and caused me

to let go of the handrail. I trudged through the deep snow in

front of the tram. Squinting, I could make out that the rails

were really covered in a deep layer of snow. It seemed the blizzard

was becoming more intense. At least here in the vast, open space,

the cold was much more severe than in the city. The snowfall

was making the layer of snow, which covered the rails even deeper.

I muddled about for a little while and then returned and knocked

on the door of the tram. The gesture seemed so absurd - a man

knocking on the door of a tram. Under normal circumstances, it

would have, at least, brought a smile. But having begun to understand

the reality of the situation, I started pounding even harder

- with my fists.

Then the door hissed loudly and opened. In the deep, dark silence

of the snow-covered steppe, this sound, so typical of urban settings,

seemed so unreal to me. It seemed so surreal - outside of time

and place. It turned out that the door had been opened, not to

let me enter, but rather to let one of the other four passengers

out.

He turned out to be a very nervous and demanding fellow, despite

how he had managed to appear so nonchalant and indifferent sitting

in the tram. Coming down the steps, he handed me one of the shovels

and snarled: "Well, we've got no other optionright? If we

don't do anything, who will? Our destiny is in our hands. When

we get tired, the other three passengers can take our places.

Take it! Take the shovel. It's not time to idle about; otherwise

we'll have to spend the whole night on the tram. I've got a lecture

to give, first thing tomorrow morning. Come on!"

I suddenly remembered the very important business meeting that

I had arranged for the morning. I blamed myself for not staying

with my friends. The weather would have been better by morning

and I could have easily gone home by taxi. But what's done is

done. I took the shovel and followed the man, hardly understanding

anything at all about the situation. The other three men and

the driver, who was still chewing, sat silently. We could see

them well in the well-lit tram, which appeared like a cozy island

in the middle of the exposed barren steppe.

We began clearing the snow, gradually uncovering the rails, which

glistened coldly in the light of the tram's headlights. The nervous

man worked almost in the same manner that he spoke: rapidly,

but not very efficiently. For the most part, he spilled the snow

all over his shoes. I didn't have much experience working with

a shovel either, but still I wasn't as pathetically helpless

as he was.

I decided to give him some advice: "You'll soon get tired

like this. Don't rush. Take a shovel full and toss the snow out

a little further away."

"All right," he replied, out of breath.

"Tell me, how the hell did this steppe appear in the middle

of the city?" I asked him, as the question had been troubling

me for quite some time.

"Steppe?" he stared at me blankly, not comprehending

what I had said.

"Right," I said. "And what do you think it is

- because we were in the city. It was snowing. I fell asleep

and, suddenly, we came upon this vast open space."

"In the city?" he asked in surprise. "Which city

are you talking about?"

He was so surprised that he even stopped working.

"Don't make a fool of yourself!" I replied angrily.

It wasn't like me to be rude to strangers. "It's a tram

and trams go through the city."

It was as if the tram heard me and thought that I was calling.

It slowly approached along the several meters of rails that we

had managed to clear of snow. Two passengers exited the tram,

approached us and, without saying a word, took the shovels from

us. They had a better knack for the job than we had had and,

therefore, the work moved along much faster.

The nervous fellow and me rushed back into the tram to get out

of the snowstorm. But still we weren't able to escape the cold,

even though the tram, lit up in the night, created the illusion

of coziness. In his compartment, the tram driver who, by now,

had finished eating, was drinking tea from a thermos.

"Listen," I addressed him as I sat down. "Where

are we now?"

Again the driver's disheveled mug appeared from behind the curtain.

He stared at me with the blurred look of a person who had just

started to digest his food. For quite some time, he stared at

me silently as if I were a subordinate who had dared to ask such

a stupid, needless question. Afterwards, he answered my question

with a question: "In what sense?"

"In the very straightforward sense." I said. "What

is this place, this steppe?" I pointed out the window, being

as explicit as possible with my gesture so that his blockhead

would understand that I thought he was an idiot and that you

couldn't answer a question with another question.

"Weird passengers," suddenly grumbled the man who remained

in the tram. "They ride and they don't know where they're

going!"

"But here," I said, losing my patience, "but we

were traveling through the city."

"In the city?" the driver asked exactly the same way

as the nervous passenger had. He was about to say something else

when the lights in the tram went off.

"That's it," he sighed with bitterness and regret.

"Now, we're stuck."

"What do you mean 'we're stuck?'" the nervous passenger

asked. "What are you trying to say-meaning that we can't

move at all?"

"There's no electric current," the tram driver clarified

with reluctance. He looked at the men with the shovels in the

snowstorm and added, "We should call them back in. There's

no point in clearing the road, we're stuck anyway." He leaned

out of the window and shouted to the passengers working with

the shovels.

The third passenger - the one who had reproached me, for God

knows what - suddenly let out a loud, weird sound. I looked back

and saw that he was sleeping. It turned out that he was snoring

like that! His poor wife! The two with shovels came back into

the dark tram and sat down separately in the seats they had had

before.

Everyone was silent. Only the rhythmic, quite strange snore of

the one passenger, calmly sleeping, broke the silence. It seems

he was as comfortable on the hard, cold seat as in his own bed.

Suddenly, we heard a terrifying howl in the night. Immediately

other long howls joined in, all on different pitches.

"What's that?" the nervous passenger asked in confusion.

"Wolves, what else?" the driver answered calmly. The

two, with the shovels who had come back in, nodded firmly and

with a slight grinning, they looked at the nervous passenger.

The discordant howling was heard again. This time the howling

was more shrill and lasted longer.

"Wolves?" the nervous passenger asked again as a chill

convulsed through his shoulders. "In the woods, right?"

"Uh huh," the driver said patronizingly and yawned.

After remaining silent for some time, he added, "Listen,

you guys,

I've had a lot of experience in this. You have to obey me."

Those two nodded, again, like twins.

"We can freeze like this," continued the driver. "We

need to make a fire beside the tram, otherwise we're in trouble.

By morning we'll be dead. It's no warmer inside here than it

is outside. We need fire. Did you understand me?"

Those two nodded again, simultaneously, even though they were

sitting apart which made their synchronic concurrence even more

striking. Neither the nervous fellow nor I said anything. The

fifth guy continued his untroubled sleep.

"Then here's what you're going to do," the driver said.

"You two go to that grove for firewood." He pointed

to the dark spot of woods that was barely discernible about a

kilometer's distance from the tram. The driver groaned in his

seat behind curtain, stooped forward, fumbling under his seat

with his hands and mumbling with effort, "Good, I've got

two axes hereThere you goTake them."

The two took the axes and silently, as if in a dream, got off

the tram. For some time, we could hear the crunch of snow under

their feet. Indeed, it was getting colder and colder for us sitting

there in the tram. I mentioned it and the driver indulgently

agreed.

"And what did I tell you?" he reminded me. "I

know the ropes in these things. No matter what you say, we won't

manage without a fire"

After some time, we heard the muffled sound of axes from the

direction of the woods.

"They're chopping the trees now," the driver said with

satisfaction.

For several minutes, we could hear rapid sound of axes. Then

suddenly it stopped and we heard a weird noise, a scream. Again,

everything became quiet for a short time, but then we heard such

distinct heart-rending human wail, that we all shuddered, except

the passenger who had been sleeping so deeply. I felt very ill

at ease. It was getting scarier because the scream lasted for

such an incredible long while.

"Damn, they got themselves into a rotten situation,"

the driver said, having waited till the scream died away. He

spoke so matter-of-factly.

"What? What do you mean? What happened there?" the

nervous passenger bombarded the driver with questions. "What

are you trying to say?"

"They ran into some wolves," the driver explained lazily.

"There's a pack of wolves out there and many of them are

cannibals. If the whole pack attacks a man, you won't even find

his bones."

He became silent and then finished rather dismayed and even remorse,

"Damn, the axes are left there, they were brand new. They'll

get lost. He turned back to me and said in confidence, "They

were not bought with public funds. I bought them myself. How

many times did I tell the boss: 'we need them, we need them'

and they didn't give a damn. That's why I had to buy them with

my own hard-earned money!"

"Listen," I said, almost exhausted by the weird things

that were happening around me. I felt like this was a nightmare

and that I had been caught up in the middle of it, having to

follow the rules as they were being dictated. "Listen, but

what about those two guys?"

"What about those two?" the driver said, indifferently.

"If they don't fight off the wolves, they'll be torn to

pieces. I guess they didn't fight them off. WellBut we still

need a fire."

"What fire? Are you crazy?! What fire are you talking about?!"

the nervous passenger interrupted, jumping out of his seat and

trying to light up a cigarette, but unable to control the flame

of the lighter in his trembling hands. The tram driver yelled

at him: "It's forbidden to smoke in the tram!"

The nervous fellow took the cigarette and glanced around quickly

to figure out where he could throw it. Obviously afraid of being

shouted at again, he didn't dare throw it on the floor. Instead

he squished it in the pocket of his overcoat. A thin stream of

blue smoke trickled out of the pocket of his new overcoat. This

scene engraved itself in my memory: the somberness of the scene:

looking out of the window of the tram to a wide steppe covered

with snow, and a stooped, trembling figure of a nervous passenger,

with a thin ribbon of smoke coming out of his pocket. The unreal

situation seemed even more grotesque. But, in spite of his fear,

which was quite noticeable, the nervous passenger did not stop

to object.

"Are you out of your mind? You, yourself, are talking about

wolves. Then why do we need that cursed firewood, if everything

is turning out to be so dangerous? Dangerous for lifeYou're simply

a madman!"

"Don't argue with me, please!" the tram driver suddenly

roared. "I've been driving this route for nearly 20 years

now, and I know more than you do about what should be done!"

He stopped shouting and assumed his normal voice: "Three

years ago on a winter night like this, six people froze to death

in my tram." He paused, looked steadily at us, trying to

figure out what kind of impression his words were having on us.

Then he continued, "I myself survived only by a miracle,

my feet were frostbitten. I had to remain two months in the hospital.

Sowhen I say 'we need firewood' that means 'we need firewood'.

If I say 'we won't survive without a fire', that means it's absolutely

true!" He again began to shout.

"So?!" the nervous passenger said, shouting back: "Then

who do you think should go this time?"

"You will go," the driver answered quietly, cooling

down immediately.

"Me?" the nervous passenger became terrified. "Not

for any price! Never! You're out of your mind! Never in my life!

Not for any"

"But I wasn't offering you any" the driver said. His

voice hardened and you could hear the iron will of his order

now. "I said, 'You will go'. Period."

Quite unexpectedly, a small revolver appeared buried in his huge

paw. The killing range of the revolver, which could hardly have

exceeded beyond 20 steps, was pointed at the nervous passenger

who, however, stood within five steps of the tram driver.

"But, but" the nervous passenger mumbled. "How

come?" In fear, he gazed at the revolver in the hands of

the huge tram driver who was now standing in the main part of

the tram, directly opposite him. I hadn't realized that the driver

was so tall; it was hard to assume that, seeing him scrunched

into his small cabin.

"But I" the nervous fellow continued mumbling. "You're

sending me to deathJust thinkThink about it. You'll be sued.

You're sending me to death," the passenger kept repeating

feverishly as if to hammer this simple idea into the blockhead

of the tram driver. "Here death threatens you not less than

there," he said.

"Shut up! Carry out my orders! Off you go for the firewood!

And you, too! March!" he pointed the revolver at me.

I knew it would be pointless to offer any excuse. The nervous

passenger had wasted them all, but still I found one, which seemed

to me, more or less, impressive and just like a drowning person1,

I grasped at it, hoping to save myself.

"And why not him?" I said, pointing at the sleeping

passenger.

For a moment the driver seemed confused. You could tell the idea

simply had not occurred to him.

"But, he's sleeping," he objected, hesitatingly.

"Wake him up," I said, "and let him go in my place."

"No way," the driver said, "Not on your life!

He'll go in his own place! And you will go in yours. All three

of you will go."

"And you also will go," I said looking point blank

at him, feeling I had nothing to lose.

"Right, right, indeed!" the nervous passenger interrupted

suddenly.

"What is this that if a person is asleep, you should send

another person to death. Gosh, what nonsense!"

"To tell you the truth, I didn't think about it," the

driver said guiltily. "Fine, wake him up," he addressed

the nervous passenger. "Didn't think," he repeated

confused, turning his head and grinning. "I simply hadn't

even noticed him. Well, he was just sleeping. And I didn't notice.

A sleeping person is like a dead person; there's little use for

him. Maybe that's why I didn't notice him." We shook the

sleeping passenger and briefly explained to him what was going

on. He blinked his eyes and stood up, yawning. He didn't seem

surprised by anything. He turned his stiff neck, which made a

cracking sound and joined us, heading for the exit of the tram.

"And why aren't you coming?" I asked the driver just

as I was about to step down off the tram.

"I can't leave this place," he said with conviction.

"No matter what happens, I must be here at my workplace.

Even if I die, I must die here. Otherwise, my kids won't get

any subsidy after my death. The contract stipulates that. So,

I'm entirely depending upon you. Go!" he said, poking my

shoulder slightly with the revolver.

The three of us got off the tram and walked across the snow,

which crunched under our feet. It was cold, but it was more pleasant

to walk than sit motionless in deep freezer of a tramcar. We

were leaving deep footprints on the even snow-white surface of

the steppe. I noticed that it was already difficult to make out

the footprints of those who had passed there before us; their

footprints were already covered with snow. We walked slowly towards

the dark forest in the distance from where, now and then, we

could hear howling turning into a threatening sound.

"I'm scared," the nervous passenger admitted in a quiet,

sad voice.

"E-eh-h! I wish I could sleep now," said the second

passenger. "I'd like to sleep eight to 10 hours. Last night

I didn't close my eyes till the very morning, can you believe.

I stayed at this chick's place, I'll tell you later what happened.

You'll split your sides laughing!"

We had passed quite a distance from the place where the tram

stood. I looked back. The windows of the tram appeared black.

The night had swallowed the number of the tram and some of the

advertisements that were painted on its side. From this distance,

it was already impossible to discern anything. I could see the

face of the tram driver. He was following us with his eyes. He

saw that I looked back and waved his hand.

End Notes:

1

Reference to an Azeri expression: "A drowning person will

even grasp at a straw."

Back to Index

AI 12.1 (Spring 2004)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|