|

Spring 2004 (12.1)

Pages

46-51

Akram Aylisli

The Heart

is Something Strange (1972)

For

the Azeri Latin version of The Heart is Something Strange, see

AZERI.org, "The World's Largest Web site for Azerbaijan

Literature and Language," created by Azerbaijan International

magazine.

Akram Najaf oghlu Naibov was born in

the Yukhari Aylis village of the Ordubad region on December 6,

1937. For his pen name, Akram chose Aylisli - the name of his

village. Most of his stories have their setting in Azerbaijan's

countryside in the villages. Aylisli is known as a writer, playwright

and translator. Akram Najaf oghlu Naibov was born in

the Yukhari Aylis village of the Ordubad region on December 6,

1937. For his pen name, Akram chose Aylisli - the name of his

village. Most of his stories have their setting in Azerbaijan's

countryside in the villages. Aylisli is known as a writer, playwright

and translator.

He graduated from the Institute of Literature named after Maxim

Gorky. Afterwards, he worked at Azarnashr Publishing House, Ganjlik

Publication, Azerbaijan magazine, and Mozalan, a satiric film

journal. Currently, he is the director of Yazichi Publishing

House.

His most famous works include: "When the Mist Rolls Over

the Mountains" (Daghlara Chan Dushanda, 1963); "People

and Trees" (Adamlar va Aghajlar, 1970]; "The Forests

on the Banks of the Kur River" (Kur Giraghinin Meshalari,

1971); "The Heart is Something Strange" (Urak Yaman

Sheydir); "What the Cherry Blossom Said" (Gilanar Chichayinin

Dediklari, 1983).

Several of his works have been staged in theaters in Baku, Nakhchivan

and Ganja. They include: "The Branches Without the Birds"

(Gushu Uchan Budaglar), "My Singer Aunt" (Manim Naghmakar

Bibim), "A Pass for Baghdad" (Baghdada Putyovka Var),

"Duty" (Vazifa), "My Mother's Passport" (Anamin

Pasportu), and "Father's Estate" (Ata Mulku). Three

movies have been made on the basis of his scripts: "Cherry

Tree", "Tale of the Lone Pomegranate," and "Surayya."

Aylisli has made translations from Russian to Azeri of works

from Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev, Vladimir Galaktionovich Korolenko,

Chingiz Aytmatov and Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

His awards include: Independence (Istiglal, 2002), which is the

highest order in Azerbaijan since the nation gained its independence

in late 1991. During the Soviet period, Aylisli was awarded:

Azerbaijan National Writer (1987), Award of Glory (1987) and

Laureate of the Lenin Komsomol Award (1968) for his work, "Tale

of the Lone Pomegranate" (Tanha Narin Naghili).

Aynur Hajiyeva and Aytan Aliyeva

were involved with the translation of "The Heart is Something

Strange". It was edited by Betty Blair.

· · ·

If Sarvar had been released

from the army at any other time, it wouldn't have been so boring

for him in the village. But he returned in the fall - late fall.

By that time, the harvest season was over and the vegetables

that his father had grown in the fields of the collective farm

had been gathered. The fodder grass that grew in the highlands

as tall as a man had been reaped and carried away - down to the

last blade. The fruit from the gardens had long been gathered

and the leaves burned. The only reminiscences of fall in the

wooded village of Buzbulag1 were five or six quince left on the

tree in Sarvar's family's yard, and the three or four yellow

haystacks of the threshing floors belonging to the collective

farm. Nothing else.

Within a few hours on his first day back, Sarvar walked through

the village and saw everything that he hadn't seen for three

years. He saw the girls and women carrying water from the spring,

men drinking tea in the chaikhana,2 and children playing dominoes at the

clubhouse just as they all used to do before. He saw the men

again gathering under the plane tree, talking about soccer and

politics. Exactly as they had done three years ago, they would

return to their homes, street by street, repeating the same words,

inviting each other for tea or supper.

On his way home that night, Sarvar saw a group of boys who were

just learning how to smoke. On the other side of the street were

some girls just beginning to whisper and giggle. He heard his

father again being referred to as "Cat Agalar" and

his mother as "Khanim With Chickens". And suddenly,

he felt so bored.

Immediately, Sarvar realized that it would be very difficult

for him to spend the winter in the village: no activity, no sound

of cars. The mountains would be covered with snow for three or

four months - Buzbulag would be totally isolated from the world.

From house to chaikhana and back again, back and forth, back

and forth. Winter frightened Sarvar. In fact, it horrified him.

Sarvar fell asleep with this horror and dreamed of a hot summer

night.

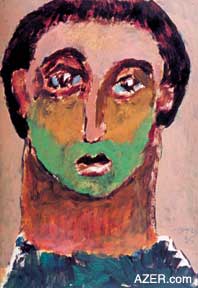

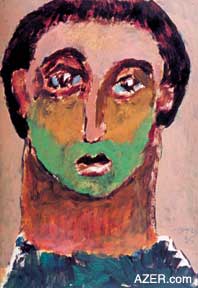

Art: Vugar Muradov. Visit AZgallery.org for contacts. Art: Vugar Muradov. Visit AZgallery.org for contacts.

He was in his father's orchard sleeping, but it was as if he

had been lifted up and from there, he could see the entire orchard.

The milky-white moonlight spread over the orchard, and large,

white melons were lying there like a flock of sheep. Sarvar was

looking at the melons, and suddenly he saw dark shadows, which

resembled blackberry bushes in the far distance near the foot

of the mountains. The shadows were stirring, whispering - as

if they were about to do something ominous. Then the shadows

began to move, approaching the orchard. A shepherd with a dark

black felt cloak came out of those shadows and raised his staff,

the big and white melons lying in the orchard began to move,

and they became a white flock of sheep following after the giant

with the black felt cloak.

Sarvar wanted to shout, but he couldn't. He wanted to get up,

but again failed. Then suddenly the dawn came, and Sarvar realized

that the man with black felt cloak had been Ajdar. He was standing

on top of the mountain, beckoning him: "Come to Baku...Come

to Baku...To Baku...To Baku...To Baku..."

Let's leave both the dream and Ajdar: the main thing was that

when Sarvar awakened the next morning, he had already solved

the problem about winter. He washed his hands and face with joy,

ate a quick breakfast, went out into the street, stopping by

a house that had long been deserted. That house was Ajdar's.

Its yard had overgrown with thistles. Grass was growing on the

roof.

It was at the teahouse that Sarvar learned that Ajdar was in

Baku. Teymur was also in Baku, selling goods at the Komurchu

Bazaar3.

Teymur had been Sarvar's classmate, so this strengthened Sarvar's

resolve even more. On his way back home, without saying a word

to his father, without taking money from his mother, he bought

some things for the journey.

Sarvar had never been involved with trade, but he had heard that

walnuts and almonds were the most profitable. That's why he stopped

by to meet some of the people who had such trees in their gardens.

He stood outside their houses and began to negotiate with their

owners just like real traders do. Finally, he struck up a bargain

with Shovkat arvad4 to buy 30-40 kilos of almonds, and

with Gulgaz arvad to buy 50-60 kilos of walnuts.

Art: Vugar Muradov. Visit AZgallery.org

for contacts.

Then

he returned home, spoke with his mother, and together they convinced

his father Agalar kishi5. Then

he returned home, spoke with his mother, and together they convinced

his father Agalar kishi5.

All the while, Sarvar imagined himself in the Baku of his dreams.

He was trading there and making money, wearing a new suit and

coat, and eventually making his way to Leningrad6 where he used to go on leave from the

army. This brought to mind an incident that had happened with

Adjar seven or eight years earlier...

It was summer and the melons were just beginning to ripen. One

evening one of the chickens disappeared that Khanim arvad had

caged in her orchard. The chicken's disappearance was discovered

the next morning. Agalar kishi and Sarvar went looking for it

in the orchard, but could find neither the chicken's tracks nor

feathers anywhere.

The next night another chicken disappeared. This time Aghalar

kishi decided not to sleep during the night but to keep watch

over the hencoop. With rifle in hand, he hid himself behind some

bushes, but he ended up falling asleep. The result was that again

another chicken was lost. Aghalar kishi got very disappointed:

it wasn't a good sign. Without a doubt only a human being could

do such a thing. No animal in the world could steal a chicken

from that iron cage.

It wasn't so much the disappearance of the chicken that upset

him, as it was that he felt somebody was trying to trick him.

And that kind of teasing would end badly because very soon the

melons would be ripening.

Aghalar kishi gave serious thought to the matter. He thought

about his enemies in the village. He even tried to figure out

which young people in the neighboring village might be guilty,

but he could never arrive at a conclusion. Agalar kishi never

did see that chicken snatcher, but Sarvar did.

One night the thief came right to the middle of the orchard,

near the shed. Aghalar kishi was asleep, snoring, but Sarvar

was awake, lying on his stomach looking down at the white melons

amidst the gray bushes in the milky-white moonlight. Suddenly

Sarvar heard someone call his name. He became so startled and

frightened that he couldn't even shout to waken his father. Then

he heard a whisper: "Hey, don't make any noise, come down.

It's me, Ajdar..."

But Sarvar was so afraid that he had no strength to move. Finally,

he could raise himself a little, and he saw the tall, lean Ajdar

standing, with his hand over his mouth saying, "shhhhhhh!"

Then Ajdar stretched his arms and helped Sarvar to climb down

from the shed. They walked to the end of the orchard without

saying a word. Ajdar stood under a walnut tree at the end of

the orchard.

"Sit down."

Sarvar did.

"Good for you, you didn't make a noise." Ajdar smiled,

placing his hand on Sarvar's shoulder.

They looked at each other for a while.

"Were you afraid?"

Sarvar didn't answer.

"Go find some bread, I'm dying of hunger...But look here,

be a man, don't wake Cat Aghalar."

Sarvar got up and went for bread. He brought back two lavash7

and some cheese. After Ajdar had eaten, he asked him very cautiously:

Were you the one stealing the chickens?"

"Yeah, it was me"

"They're looking for you in the village."

"I know."

"Five or six policemen came to the village."

"Is that so?"

"They asked us about you, too. Father told them that you

were in Baku. By the way, you were in Baku, weren't you?"

"I was."

"But why didn't you stay there?"

"They found out where I lived. Some scoundrel betrayed me."

"What are you going to do now?"

"I'll hide somewhere and when everything is quiet, I'll

go back again.

Sarvar asked no more questions because everything was clear.

Three or four months ago when Ajdar was working at the cannery

in the region, one day he took 3,000 manats belonging to the

State. Everyone knew about it in Buzbulag. Then somebody had

seen Ajdar selling goods in one of the markets in Baku. The news

spread quickly through the village. During these three or four

months, Sarvar had heard hundreds of stories about Ajdar. Now

this young man, who had been his former neighbor and whom Sarvar

used to see every day, was like a stranger, a character out of

a tale. Sitting beside him now in this field at midnight seemed

so strange...

Sarvar remained silent. After some time, he asked cautiously:

"And where do you sleep at nights?"

This time, instead of answering, Ajdar studied Sarvar's eyes

for a long time. He looked and looked until Sarvar became confused

and even frightened. Finally, he said: "Will you betray

me if I tell you?"

"No, noWhat are you saying, I won't tell anybody!"

"Swear."

"To what?"

"What do you believe in?"

Sarvar thought a lot, but couldn't find anything to swear to.

Ajdar pointed to the moon in the sky and said: "Do you believe

in that?"

Sarvar raised his head and looked at the moon. That night the

moon looked so big, so awesome, that one couldn't help but believe

in it. That's why Sarvar said very enthusiastically: "Yes,

I do!"

"Swear then."

"I swear by the moon that I won't tell anybody about it!"

"Then follow me..."

After walking quite a long distance, they reached the bottom

of the mountain, the place that Buzbulag people called "Ilanmalashan"8.

Here - behind the thicket of blackberry bushes - under the branches

of one of the fruit trees, surrounded by shrubs and thorns, Ajdar,

had made himself a shelter. In order to enter it, you had to

get down on your stomach and crawl beneath the blackberry bushes

for quite a stretch.

Moreover, the moonlight could not penetrate through the bushes.

Ajdar's pocket flashlight barely illuminated that fairy world.

That night Sarvar was so surprised at not seeing a single snake

in this place which was considered a snakes' nest by the Buzbulag

people. After crawling awhile, they entered a glade. And Sarvar

was astonished as he stood in front of Ajdar's shack, which was

like an enormous spider's web. Ajdar had cleared the thorns and

shrubs from the spacious area in front of his hut. He had dug

and smoothed the ground and even splashed water over it. Behind

the hut, there was a tiny trickle of a spring. Ajdar had made

a pond in front of the spring and the water was shimmering in

the moonlight. A bonfire was burning in front of the hut, and

a dirty, black kettle was beside the bonfire. And then Sarvar's

eyes fell upon the bones of the chickens that he had stolen from

the orchard.

As if to surprise Sarvar even more, Ajdar stood beside the door

of his hut and before entering, gave a low whistle. It was as

if he were calling a puppy; but instead, a hedgehog came out

of the hut. The hedge-hog didn't surprise Sarvar. What did surprise

him was the fact that it was wandering around with its head stuck

out. In order to make a hedgehog stick out his head, children

used to toss them into the pond, and play pranks on the poor

animals. It was the first time that Sarvar had ever seen a hedgehog

walking about like that, in the presence of people. It was as

if the hedgehog was conscious of this. Seeing Sarvar, it rolled

itself up into a ball and hid its head. Ajdar liked the way it

did that.

"He's my brother," he said.

"He's an orphan like me, and he's very honest, too. He gives

no rest to those snakes. He guards me while I'm sleeping."

The items inside the hut were familiar to Sarvar: Ajdar's sheepskin

coat, an oil lamp, a water bucket that had belonged to Kava arvad

who had passed away, a saucepan. Ajdar had managed to bring all

these items from his house at night.

· · ·

Every day of his military service,

Sarvar thought about that scene with its hut, the puny spring,

the hedgehog, even the black kettle and the smoky oil lamp. It

was no laughing matter. For a month or more, he had been making

runs to the bottom of the mountain, carrying down food for Ajdar.

He always waited for his father to go to sleep or he would deliberately

mislead him, and pretend to be taking a walk in the orchard.

For a month or so, he and Adjar had gathered wheat, peas and

beans from the fields of the collective farm and cooked porridge.

Sarvar had never eaten any wheat porridge tastier than that in

his life. And Sarvar had never experienced days more wonderful

than those they spent together - despite the fear and dread in

his heart.

Of course, it was not so easy to keep such a big secret. Besides,

people were still on the lookout for Ajdar. Police were still

coming to the village looking for him. And at school, especially

at Zinyat's lessons, Sarvar's situation became even more awkward

because during every lesson, she was talking about bravery and

courage and about being watchful for any enemy.

According to her definition, undoubtedly Ajdar was an enemy and

a real spy. Moreover, Sarvar had not been a child then, he was

in the 6th grade. He knew what stealing money from the government

meant. Nevertheless, only on one occasion had Sarvar thought

about revealing his secret, and showing the Ajdar's hideout that

would lead to his arrest. But that very night, when he saw Ajdar's

face there in front of the hut among those bushes and thorns,

Sarvar became more committed than ever to keep the secret. There

in the moonlight, Ajdar did not seem like an enemy or spy at

all; he was just Ajdar - tall, lean, and to a certain extent,

resembling the late Aunt Khavar...

That year Sarvar spent all of September experiencing feelings

of fear and anxiety mixed with a strange joy. Sometimes, he couldn't

sleep even for one or two hours at night. But Ajdar was sleeping

all day long; his eyes had even become swollen from so much sleep.

And as Ajdar had found nothing else to do, he was gathering grasses

from the mountainside and making wonderful things like a basket,

pail, and jug. Often he would destroy the pond in front of the

spring in order to build it again. Sometimes he wrote poems:

Poor hedge hog, guard me,

I'm a refugee from my native land.

I've left my home and village,

And have become a fox in the woodlands.

The beginning of Ajdar's last

poem went like this:

You, merciless world, look at

the Moon in the sky...

You, merciless world, look at the Moon in the sky...

Sitting in front of his hut

and looking at the moon, Ajdar repeated those words five or ten

times. But he couldn't compose the rest of the poem. Sarvar had

no notion how the rest of the poem went.

And in the fall when the rains began, one night they parted in

front of the hut, without saying a word. Ajdar took only his

sheepskin jacket and picked up the hedgehog in his arms. And

though it would have been very strange, Sarvar thought that Ajdar

was going to take the hedgehog to Baku. But instead, Ajdar kissed

the hedgehog's wet nose and put it down. Then Ajdar hugged Sarvar,

and for some reason, kissed his nose, too. Then he climbed up

the mountain swiftly like a hawk, and waved his hand goodbye

to Sarvar: "Come to Baku...Come to Baku...To Baku...To Baku...To

Baku..."

· · ·

Now they were standing face

to face in front of Taza Bazaar9. Ajdar had gained a lot of weight. He

was breathing heavily and looking at Sarvar very angrily. Sarvar

couldn't understand the reason for that anger.

"Why have you come here?" was Ajdar's first question.

Sarvar replied: "I've come to sell goods. Afterwards, I

want to go to Leningrad.

For a long time Ajdar looked at Sarvar's ironed trousers and

his black coat under which was a white woolen sweater with red

stripes, the kind that only the old women of Buzbulag knew how

to knit. He was thinking about something while he looked at Sarvar:

"Are you going to sit in the market looking like that?"

he asked.

Ajdar took something that looked like dry grass out of his pocket.

After smelling it, he coughed for a while. Then he asked: "What

have you brought?"

"Almonds and walnuts. There are 115 kilos all together."

"Where have you taken them?"

"To Komurchu Market. I have put them with Teymur."

Ajdar looked at the street very thoughtfully. Then he stopped

a taxi that was passing by and said to Sarvar: "Go, put

them in a taxi and bring them here!"

After awhile, they took two enormous sacks out of the taxi and

put them by a man whom Sarvar didn't know in the bazaar. Then

they left by the upper door of the bazaar and walked down to

Basin Street. It was snowing. The snowflakes melted as they touched

the steaming ground. In this nasty weather with head bent down,

Ajdar was taking Sarvar somewhere along the tram line, without

saying a word.

Sarvar wanted to ask where they were going but didn't dare. He

wanted to remind him of the chicken incident, and to talk about

that summer, the hut, the hedgehog. He wanted to recite that

poem to change Ajdar's mood, just to make him laugh. But he kept

silent. He was afraid that Ajdar would misunderstand and would

think that he was trying to remind him of the kindness that he

had done for him that summer and to hint that he wanted something

in return. Nothing else crossed Sarvar's mind to talk about.

So they continued walking like this, not saying a word. Finally

Sarvar could keep silent no longer and asked: "Look, Ajdar",

he said, "I've not come to give you any trouble! Go, if

you have something else to do. It isn't the first time that I'm

in a big city, I've been in Leningrad for three years."

"Good for you," replied Ajdar, who said nothing more.

They turned the corner and entered a small courtyard. There was

an old house in the yard with a verandah. An old, gray-haired

woman was ironing clothes on the verandah.

Ajdar left Sarvar in the yard and went up speak with the woman

for a while. Afterwards, he called Sarvar upstairs.

"Come up, you'll stay here," he said, opening one of

the two doors overlooking the verandah. "Here's your room

and there's your bed Have some tea, then take a rest and sleepGo

for a walkthen go to the cinema. This is Margo, she's Georgian.

She lives aloneIf you need some money, ask herDon't worry about

market affairs, I'll take care of everything." Of course,

such arrangements didn't satisfy Sarvar. He felt that Ajdar still

considered him a child. He got offended because while Teymur

was in the market, but Ajdar wouldn't let him go to the market.

But Sarvar dared not go out against Ajdar's advice and refuse

him outright.

That day Sarvar walked around the city until evening. In the

evening, he returned home and waited for Ajdar. But Ajdar didn't

come home that night - nor the next. Sarvar waited until noon

the following day. Then he rushed off to the market, but he couldn't

find him there. Neither could he find his own goods at the market.

The man with whom he had left his goods had disappeared as well.

On his way from the market back to Margo's place, Sarvar tried

to figure out where Ajdar could be, but he could reach no conclusion.

Furthermore, Margo didn't tell him where Ajdar was. It was as

if she deliberately hid it from him.

Teymur was the only person whom Sarvar could ask for help. So

towards evening, Sarvar went to the Komurchu Market and found

him there: "Hey, Teymur, have you seen Ajdar?"

"Yes, he went to Tbilisi this morning."

"What? He's gone to Tbilisi?"

"Yes, he's gone."

Sarvar could hardly keep himself from crying like a child.

"Didn't he say anything about me?"

"He did. He said that you should walk around in the city

and then leave for the village. He said that you couldn't be

a trader."

Sarvar shouted as loud as he could: "But what about my money,

what about my goods?"

Teymur didn't lose his temper: "I don't know anything about

your money," he said. "That's your own business. I'm

telling you what I was told to tell you. He said that you should

leave for the village on an odd day of the week, not an even

one. He has a friend who works as a conductor in the seventh

passenger car. He said that you shouldn't buy a ticket. He has

already spoken to the conductor about you. The train leaves at

one o'clock at night. Just remind the conductor of Ajdar's name.

The seventh passenger car, don't forget..."

If they had not studied together at school for 10 years, maybe

the conversation would have ended there. But it didn't. While

saying those final words, Teymur had become a bit indiscreet

and chuckled. It was at that very moment that Sarvar sensed that

Teymur was hiding something from him. Sarvar could detect something

in his eyes, like a trick, that's why he suddenly collared Teymur

and demanded: "Ajdar has not gone to Tbilisi. You're lying

to me. You know where he is. You're holding something back from

me!"

Teymur tried to pull away. "Ajdar has been living illegally

for 10 years, he has no permanent residence."

Sarvar replied: "You said he's gone to Tbilisi, didn't you?

Be a man, have a conscience! I see that you're lying, I can see

it in your eyes!"

Teymur didn't say a word for a while. Sarvar felt that Teymur

had become softer and so he spoke more calmly. "I thought

he was a normal man," Sarvar said. "How could I know

that he was a villain, a beggar? He has taken a ton of my stuff.

Could he really be such a criminal?

"It's your fault. Why didn't you sell your stuff yourself?"

said Teymur.

And here Sarvar lost his temper again: "He's the one who

is dishonest. He wouldn't let me sell the stuff myself. How could

I know that he was as cunning as a fox? How could I know that

he was a rascal, a lowdown?"

Teymur said nothing again. Without saying a word to each other,

they gathered everything on the counter and asked the guard at

the market to watch over it for them. Then they left the market

and didn't talk about Ajdar for a while.

"Do you see this weather?"

"It's so cold! - But it's clear, see? It's like Buzbulag's

weather."

Sarvar replied: "I wonder if it's snowing in Buzbulag too.

It was raining when I left."

And here, Teymur decided to bring up the subject of Ajdar again.

"Ajdar gets bad attacks in such weather, he said."

"What kind of attacks?"

"Don't you know? Ajdar is ill. He's suffering from asthma

or something like that. When it gets cold, the poor guy can't

breathe. When the weather is like this, you won't find Ajdar

in the market. There's a restaurant down by the sea. Actually,

it's more like a cellar than a restaurant. Ajdar goes there and

sits for hours in such weather."

"You think he might be there now?"

"Maybe, I don't know exactly. But please, don't tell him

that I've told you about this!"

Sarvar said nothing else. Leaving Teymur, he ran towards the

sea and found Ajdar, sitting in a dark corner of that cellar

restaurant.

"Oh!..So the guy hasn't gone to Tbilisi, so he's here! Scoundrel!

Scum!"

"Take a seat, Cat Aghalar's son, don't carry on like that,"

Ajdar said.

Sarvar insisted: "Let's go. Give me back my stuff. I won't

sit with such a scoundrel as you."

Ajdar grabbed his hand and made him sit down. "I've sold

your goods. See? I'm drinking them now, little by little,"

he said, pointing to the bottle of vodka on the table.

"If you don't give my money" said Sarvar, clenching

his fists.

Ajdar gently took his arm: "Let's go outside and you can

beat me up there," he said. "But not here, Cat Agalar's

son!"

"Are you making fun of my father? O.K. We'll see. We'll

discuss it outside!"

Ajdar replied, "I'm deeply indebted to Cat Aghalar for bringing

up such a son like you!"

He poured vodka for Sarvar too. Then he called the waiter and

ordered a meal for him. But Sarvar touched neither that meal

nor the vodka.

"I wish I would have gotten you arrested back then,"

he said. "You wouldn't have turned into such a scoundrel

now."

Ajdar didn't lose his temper, he just smiled. Then he asked,

unexpectedly: "Why do you want to go to Leningrad? Do you

have a girl friend there or do you just want to go there to trade

in the markets?"

Sarvar replied, "It's none of your business. Just give my

money!"

Ajdar kept silent for a while. Then he took five or six almonds

out of one pocket and three walnuts from the other. He placed

them on the table and looked at Sarvar.

"Do you recognize these?"

"They're mine. I'll get them all back, from your throat,

one by one!"

"Drink your vodka."

"No, I will not!"

"Eat your meal."

"I will not!"

Ajdar took one of the almonds that he had put on the table. "These

are Shovkat arvad's almonds. Right?"

Sarvar was surprised.

"And this is from Gulgaz arvad's walnut tree near our fence,

opposite the pussy willow tree in your backyard. There was a

fig tree next to that pussy willow; its leaves used to remain

deep green even in the fall. Then there was a cherry-plum tree

by the stable, very close to the wall, it used to blossom in

the fall. Is that cherry plum tree still there?"

Sarvar replied: "Why not? Why shouldn't it still be there?

Don't try to fool me. Give my money."

"And is that pussy willow still standing there, too?"

"Are you kidding me?"

"I'm not kidding you. I'm simply asking if that pussy willow

is still standing there."

"Yes, it is. So what?"

"I kissed Mursal's daughter under that pussy willow."

Sarvar said: "You're drunk, you're talking nonsense!"

Ajdar kept silent, then he coughed, and a horrible wheezing sound

came from his chest and suddenly a strange, frightful voice came

out of that wheezing: "Go and tell that pussy willow that

Ajdar is dying!"

And suddenly Sarvar saw Ajdar's eyes fill with tears. He realized

that Ajdar was crying. Tears fell onto the collar of his jacket.

He felt sorry for Ajdar and wanted to comfort him, but couldn't

think of anything to say. Instead, he reached for the vodka in

front of him and drank it off...

"Eat your meal."

"I don't want it."

"Do you want another bottle of vodka?"

"As you wish."

Another bottle of vodka was brought to the table.

Sarvar intentionally drank too much. He drank because he didn't

want Ajdar to drink so much and become drunk. But Ajdar was already

drunk.

"What's the date today?"

"The thirteenth."

"Today is the happiest day of my life."

"Let's go," Sarvar said. "The restaurant is closing."

After the lights of the restaurant were turned off, they got

up. Ajdar put three 10-manat bills on the table, and left the

restaurant without saying anything to the waiter. It was cold

outside: the ground was frozen; the empty street was glistening

in the moonlight.

"What time is it?"

"About twelve."

"You'll go today."

"But why?"

Ajdar turned towards the Boulevard and headed towards the sea

for a while. He was out of breath. Finally, he said: "You

aren't cut out to be a trader."

"I haven't come to be a trader."

"Then why did you come?"

"Didn't I tell you? I've come to see the city. Then I want

to go to Leningrad."

"I also came to see the city," Ajdar replied, "and

as you see, I'm still here."

"But you're different than me. I haven't stolen money from

the government," insisted Sarvar.

And then a horrible wheezing sound came from Ajdar's chest, making

Sarvar feel sorry that he had said those words. Ajdar placed

his hands on his chest and leaned over the iron railing close

to the sea. He was coughing, Sarvar felt very sorry that he had

spoken that way to Ajdar. It took a few minutes before Ajdar

could raise himself a little. He raised himself, but didn't make

any comments. They stood gazing at the sea...The moon was high

in the sky and the sea was faintly shimmering in the moonlight...

"I didn't steal any money,"10 Ajdar said when he was able to speak.

"Mursal asked me for that money. He said he needed it desperately.

I took the money from the safe in the office and gave it to him.

I thought I was doing him a favor. How could I have known it

was a trick? The next morning a special commission came and checked

my safe and my accounts. Of course, I couldn't tell them about

Mursal so I ran away so they couldn't arrest me. Thus, Mursal

was rid of me. Simply, he didn't want me - an orphan - to marry

his daughter. Since then, I've been on the run and hiding."

"It seems my words had a bad effect on you. I'm sorry, I

shouldn't have said that."

"Oh, no, I'm thinking of something else."

"What?"

"Today, I saw something very strange in the bazaar. I've

been thinking about it since morning. A small dog was chasing

a big dog. The small one was pure white and very little. In fact,

it didn't look like dog at all."

"What's so strange about that?"

"What's strange about that? Such a small dog chasing a big

one! I wish you could have seen how it was chasing that big dog.

And the people were watching and laughing."

"You're drunk! You have a fever!" Sarvar said.

Ajdar continued: "Do you know why that big dog was running?"

Sarvar replied: "I don't know, let's go."

"Where?"

"Wherever you wish."

Ajdar said: "Then let's head down to the railway station."

They started walking towards the train station. A bit later Ajdar

again started talking about the dog. "I'm not surprised

that the big dog was running. What I'm surprised about is that

not a single person in that crowd knew why that big dog was running

away from the small one..."

"Did you know why?"

"Of course, I knew! That big dog understood very well that

the whole crowd was on the small dog's side, and that they would

support the little one, not him. That's why it was running."

"So, what does that mean?"

"Nothing!" said Ajdar angrily. "I just want to

say that I felt sorry for that dog."

They were walking silently for some time, the frozen road, scraping

under their feet. Then Ajdar sat down on a bench:

"What time is it?"

"Half past twelve."

"Then we have just a little time left!"

"For what?"

"Before the train leaves."

"But why are you pushing me away? Because you've spent my

money?"

"No, it's because I know that you'll get into trouble here,

and very soon."

"But why doesn't Teymur get into trouble?"

"Teymur will never get into trouble."

"Then why would I get into trouble?"

"Because you're honest!"

Again there was that hoarse voice, that hissing sound. Ajdar's

eyes became redder and redder. Sarvar felt very sorry for him.

He was confused. Should he leave? If so, how? Should he stay?

What for? He had already lost hope at the restaurant of getting

his money back from Ajdar. Suddenly Sarvar looked at his watch

and said: "I'm going."

"I hope you're not lying."

"Have I ever lied to you before?"

Ajdar got up and said: "You can get your money from the

conductor. The seventh passenger car. Teymur already told you.

There are 500 manats there in total. You'll receive it after

reaching the village. This street will take you directly to the

station. Go. I feel ill, very ill. I can't accompany you to the

station."

· · ·

It was a wad of 10 manats. The

money was inside a folded piece of paper. Something was written

on the paper:

"I didn't want you to stay in this town,

To stay here and be like me.

The time will come and you will understand my words,

Come and pray for me over my grave."

Sarvar put the money in his pocket, read those lines in the presence

of the conductor, and then, folding the paper, slipped it into

his pocket.

He wasn't surprised at all that Ajdar's had written his note

in poetry. When Sarvar was still studying at school, he had written

a note to a girl in verse. Since that time he knew that there

were some things in the world that could only be expressed in

poetry...

End Notes:

1

Buzbulag is the name of the village in which many of Aylisli's

stories are set.

2

Chaikhana is a teahouse. Traditionally, in villages, only men

gather there - not women.

3 Komurchu

bazaar in Azeri mean charcoal-dealer market but, in fact, people

sell everything there.

4

Arvad is a word attached to the first name of an elderly woman

to show respect, as in "Khavar arvad" and "Shovkat

arvad".

5

Kishi is a word attached to the first name of an elderly man

to express respect, as in "Agalar kishi".

6

Leningrad. After the collapse of the Soviet Union in late 1991,

the name of Leningrad was changed back to St. Petersburg.

7

Lavash is a traditional kind of bread, paper thin, which bakes

with a minimum of fuel.

8

"Ilanmalashan" means "the place where snakes live".

9

Taza Bazaar means New Market and is one of the major markets

in the center of Baku.

10

This paragraph, explaining why Ajdar had stolen the money from

the State to assist the man who he hoped would be his future

father in law, was omitted from the version that was published

during the Soviet period. The author assumed it was because this

explanation exposed that blackmail existed during the Soviet

Union. In literature and the arts, the nation was always supposed

to be glorified as an ideal state.

Back to Index AI 12.1 (Spring

2004)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|