|

Spring 2004 (12.1)

Pages

80-81

Samid Aghayev

On Loving

Your Neighbor (1994)

O Lyubvi k Blizhnemu (in

Russian)

Samid

Aghayev was born in Lankaran near the southern border of Azerbaijan

on August 17, 1957. Since 1978, he has been living in Moscow.

Currently, he is a professor at the Maxim Gorky Literary Institute. Samid

Aghayev was born in Lankaran near the southern border of Azerbaijan

on August 17, 1957. Since 1978, he has been living in Moscow.

Currently, he is a professor at the Maxim Gorky Literary Institute.

His major publications include two collections of short stories:

"Cadillac for a Younger Brother" (1994) and Dreams

(1997). For his short novel, "Romance of the Unloving",

he was named Laureate of the Katayev Literary Prize (1996).

He also has written a historical novel, "Seventh Perfect"

(2001), for which he won a Moscow prize in the field of literature

(2002).

"On Loving Your Neighbor

as Yourself" describes an episode in the life of a simple

worker, who truly does try to be sensitive to what he perceives

are the economic needs around him, only to discover that he has

been tricked. This story was translated from Russian by Arzu

Aghayeva and edited by Betty Blair.

· ·

·

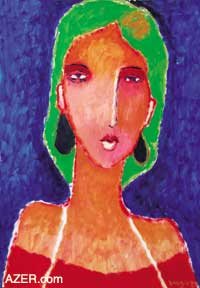

Art: Vugar Muradov. Visit AZgallery.org

for contacts.

Azim

was sitting on top of a pile of scrap metal, his canvas work

gloves under him. The workers had left for lunch. But since he

had already eaten the cutlets1 that he had brought from home, he looked

out through the open door towards the river with its green water

and reeds, and to the fields beyond, and the peaks of the distant

mountains. It was snowing - as it can snow only in the subtropics.

Huge snowflakes were floating down lazily as if trying to decide

whether they wanted to go back up again or not. Azim

was sitting on top of a pile of scrap metal, his canvas work

gloves under him. The workers had left for lunch. But since he

had already eaten the cutlets1 that he had brought from home, he looked

out through the open door towards the river with its green water

and reeds, and to the fields beyond, and the peaks of the distant

mountains. It was snowing - as it can snow only in the subtropics.

Huge snowflakes were floating down lazily as if trying to decide

whether they wanted to go back up again or not.

Azim was smoking. Through the puffs of smoke, he could make out

a figure of a man who had entered. He wasn't tall, nor was he

young or shaven. He wore a jacket over his sweater and galoshes

but no overcoat. Azim's attention was drawn to the thick-knitted

socks in which the man had stuffed his cheap striped pants.

The man looked around and approached Azim, muttering a greeting.

"They say you can buy a gas heater here, right?"

Azim nodded reluctantly.

"Big problem," he said. "Big demand."

"What's the price?"

"Depends on the demand," noted Azim, finishing his

cigarette. "Sometimes they're expensive, sometimes cheap."

"May I take a look?" asked the visitor.

Azim stood up and went to the corner where a gas heater was lying

behind some equipment covered with clothes.

"Does it heat well?"

"Very well. You can heat anything on it. A kettle will always

stay hot. You can even cook on it."

"How much is it?"

Azim coughed. Saying the price had always been a problem for

him. In reality, Azim was doing everything just like others did.

He bought the heater pieces from the scrap metal man and made

heaters, which really were not of lesser quality than the other's.

But when it came to saying the price, he would always get embarrassed

and say less than he intended to. His price was 25 rubles; others

sold theirs for 35 but, actually, he had only managed once to

sell it for 25. And then after loading the heater into the trunk

of the client's Zhiguli2, Azim had returned to count the money

only to discover that he had been shortchanged three rubles.

"Twenty-five," he said firmly.

The buyer took a pack of Avrora cigarettes3 out of his pocket and offered one to

Azim. Azim didn't smoke cigarettes that didn't have filters,

but he didn't dare refuse and take out his own cigarettes. He

didn't want to offend the man. He lit the cigarette, tasting

the bitterness on his lips.

"Khan Kishi," said the man, introducing himself. Azim

bent his head ever so slightly so that Khan Kishi would not see

him spitting out small pieces of tobacco that had stuck to his

lips.

"I work close by here," Khan Kishi began, "as

a tractor driver of MTS [Machine Tractor Station]. I drive repaired

tractors in our section. The salary is low. Of course, if I worked

in the field, I would get much better money, though the wages

there have also decreased.

Khan Kishi gently slid his palm over the heater.

"Good thing. I've been thinking of getting a heater for

quite some time. My family is freezing. Does the State provide

any heaters? No. If only I had money, I would buy it immediately.

I wouldn't even bargain.

Azim felt a lump form in his throat. As if sensing it, Khan Kishi

looked at him, sadly: "Yesterday, they promised to pay us

in advance and give us the 13th.4 But they didn't. They said there was

no money in the bank. Otherwise, I would buy it. But I don't

have enough moneyIt's so cold at home; the kids are freezing

and there's no use counting on the State for heating. We hardly

have any gas coming through."

He hung his head.

Azim had paid five rubles for the parts, plus he had to pay three

rubles to the craftsman for covering up that he was doing this

work on the side.

"How much money do you have?" Azim asked.

Khan Kishi searched in his pocket and pulled out two crumpled

five-ruble notes. Azim shook his head and lit up a new cigarette.

Khan Kishi slapped his hip pocket and then searched the inside

pocket of his jacket and produced another five-ruble note: "I

just remembered," he said, "my wife gave me this to

buy sugar. So?"

Azim finished his cigarette, suffering under Khan Kishi's begging

eyes. In frustration, he extinguished the cigarette butt with

his shoe.

"OK, take it," he agreed.

"Can I have the cloth as well?" the tractor driver

asked. Azim gestured resignedly. Khan Kishi carefully wrapped

the long-awaited heater in the cloth and headed out the door.

He was limping a little under the heavy load.

"Seven rubles is also money," Azim rationalized, as

his eyes followed the figure of the man.

· ·

·

"Our man came," announced

the sister.

"He came, my son," said the mother happily, holding

her sewing in her hands.

"Good evening," said Azim. He took off his jacket and

headed to the table. His sister brought a washbasin. With the

jug, she started pouring warm water on his hands. His mom was

looking at them contentedly.

Azim could just as easily have washed his hands with cold water

in the washbasin in the yard. But this was their ritual - woman

taking care of breadwinner. Everybody got a lot of pleasure from

this: the women who were tired of living at home without men,

as well as Azim, who suddenly felt himself a grown man.

Before dinner, Azim would usually take out his earnings and share.

And this also became a small family ritual.

"Not much today," Azim said, "I got a poor client

and took pity on him and sold for a cheap price."

"That's all right," his mom said. "You did right

in the sight of God."

Azim nodded as he started to eat.

· · ·

"What's this you've brought?"

Khan Kishi unwrapped the cloth.

"It's a gas heater, a very good one. The kettle will always

stay warm; you can cook on it."

"Was it expensive?"

"Yeah, they just rip you off. But what to do, I had to pay

35 rubles."

"A bit expensive," his wife said, shaking her head.

"But that's OK, woman," Khan Kishi boasted. "I'm

rich today. I got an advance, plus "the 13th" - 200

rubles in total. Here you are, put it aside."

The woman took the money and started counting it.

"But you've got only 165 rubles here. Did you pay for the

heater out of this money?"

"Do I have to give you a report? Whatever I've brought,

just say thanks and give God the praise."

His wife didn't say anything. She wrapped the money in a cloth.

Three times she pressed it to her lips and forehead.5

Then she hid it in one of the bowls in a niche in the wall just

below the ceiling.

"Do you want to eat?"

"No, I was just at the chaykhana [tea house]. I had a little

something to eat and drink there."

Khan Kishi went in to see his sleeping kids. He kissed them and

headed off to bed.

"So, did you pay for the heater out of this money?"

his wife asked in a sleepy voice.

"But did I have any other money?" Khan Kishi noted

ironically, snuggling up to his wife.

End Notes:

1

Cutlet is a traditional dish, made with ground meat and seasonings,

shaped something like flat, oblong hamburger.

2

Zhiguli refers to a popular Soviet-manufactured car.

3

Avrora cigarettes are very cheap Soviet cigarettes. Khan Kishi

wanted to show that he was very poor.

4

13th refers to the Soviet period when the government used to

pay something like a bonus, equivalent to a month's salary.

5

People kiss objects as a gesture of respect. For example, they

will pick up a piece of bread that has accidentally fallen on

the floor or ground, often they will place it on their forehead

and kiss it three times. Thus they show their respect to things,

which are considered sacred - especially products made of flour

and sugar.

Back to Index

AI 12.1 (Spring 2004)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|