|

Summer

1999 (7.2)

Pages

81-83

Nusrat Hajiyev

(1948-

)

Yesterday

and Today, the Same -

We're Just Characters That Change Clothes

Visit AZgallery.org for more works of Nusrat Hajiyev Visit AZgallery.org for more works of Nusrat Hajiyev

The intriguing

characters in Nusrat Hajiyev's paintings look historical, but

they're not meant to seem old-fashioned. You'll find the men

dressed in baggy Turkish pants and turbans, while the women wear

long dresses and veils, reminiscent of the traditional dress

a century ago.

Nusrat doesn't paint this way out of a sense of nostalgia or

sentimentalism, but says, "Life today is still the same-we

merely change our clothes." People wear clothing designed

by Christian Dior today, Nusrat says, but he believes that their

conversations, temperaments and emotions are the same as in the

past. "You'll find someone hiding something from another

person, someone trying to cheat another, and someone loving another

with the same intensity and devotion as Romeo and Juliet did

in the past." Nusrat's fusion of the past with the present

lends a timeless quality to his work.

_____

I remember that when I was about four or five years old and wasn't

yet able to read, I had a book with wonderful illustrations in

it. It was hard to separate me from that book. I used to become

absorbed in those pictures. We were living in Ganja [north central

Azerbaijan] at the time. Later during a move to Baku, the book

was misplaced. It took us a couple of years to finally locate

it, stashed away among some of my parents' books. I immediately

remembered the book and since I could read by then, I found out

that those drawings were made by an Italian artist. That book

was my first introduction to art. Today, illustrating books brings

me the greatest satisfaction of all.

Of

course, I've had many kinds of artistic influences in my life.

My father Suleyman was an architect who was involved with the

theater and occasionally played the role of an artist in plays.

He also made drawings. Elchin Mammad [a distinguished illustrator]

is my relative. The famous Azerbaijani composer Fikrat Amirov

[1922-1984] was my uncle [See Winter 97, AI 5.4]. I also had

an aunt who was an actress. So I became an artist because I realized

there was such a profession, thanks to the people who were part

of my everyday life. Of

course, I've had many kinds of artistic influences in my life.

My father Suleyman was an architect who was involved with the

theater and occasionally played the role of an artist in plays.

He also made drawings. Elchin Mammad [a distinguished illustrator]

is my relative. The famous Azerbaijani composer Fikrat Amirov

[1922-1984] was my uncle [See Winter 97, AI 5.4]. I also had

an aunt who was an actress. So I became an artist because I realized

there was such a profession, thanks to the people who were part

of my everyday life.

However, it seems to me that primitive man is the most genius

of artisans. He is the one who began the whole process of artistic

expression in the beginning by picking up a stone or sharp object

and drawing his impressions on cave walls. Somehow he had this

urge to create and document the beauty of life around him. He

wasn't just occupied with satisfying his physical needs.

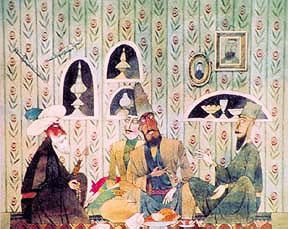

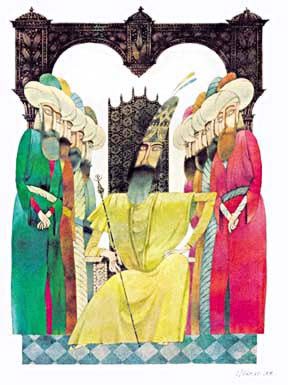

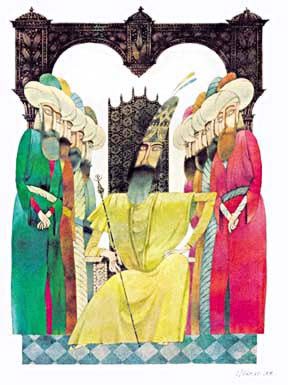

Left: Nusrat Hajiyev, "The Shah", 18 x 25 cm, watercolor

on paper, 1998. Packed together like sardines, the Shah's subjects

are passive and servile, expressing no personalities of their

own.

Later when I started attending Baku's Art School (1969-1974),

I had already decided what kind of artwork I wanted to do-watercolor

miniatures related to history and folklore. I drew a lot of inspiration

from 13th- and 14th-century artists such as Soltan Mohammad and

Behzad. They were members of the famous miniature school in Tabriz,

one of the most developed art schools of its time. Soltan Mohammad

brought the portrait genre to this school with works such as

"The Prince with a Book," which is supposed to be a

portrait of the Safavid ruler Tahmasib, who ruled a region that

extended 1 million square kilometers and included Iraq, Iran,

Armenia and Azerbaijan.

At the time, my desire to pursue miniature artwork would have

been considered "nationalistic" and severely reprimanded

and discouraged. Other artists who had tried to express nationalistic

views ran into difficulties and couldn't get their works exhibited.

For example, when I was a student, there used to be art exhibitions

at the Lenin Museum in Baku [now the Carpet Museum]. One day

when I was passing near the Boulevard, I saw Rasim Babayev [see

page 45] walking with his head down and a painting under his

arm. The work, called "Pistachio Tree", had been pulled

from the exhibition that was to open the following day. I still

remember the dejected look on his face. It was the first indication

I had of how things could be for me in the future. But still

artists like Rasim and Kamal Ahmad [see page 66] used to bring

their works to show exactly how they were working, even if their

works were usually rejected. Today, they are among the most respected

artists in our country.

Public vs. Private

I soon learned to make

a distinction between public and private art. I created two kinds

of works: one for society and the other for myself. The first

group of works was shown in exhibitions organized by the Artists'

Union. The second group remained privately in my studio. I soon learned to make

a distinction between public and private art. I created two kinds

of works: one for society and the other for myself. The first

group of works was shown in exhibitions organized by the Artists'

Union. The second group remained privately in my studio.

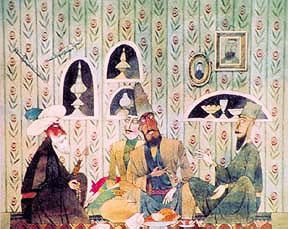

Left: Nusrat Hajiyev "Old Baku", 26 x 22.5 cm, watercolor

on paper, 1997.

For my public art, I made posters for exhibitions. They were

easy. Each poster was dedicated to a certain theme. As part of

our homework for art school, we created works for exhibitions

around certain themes. For example, there were exhibitions dedicated

to the October Revolution, Women's Day or Lenin. A few months

prior to each exhibition, the theme would be identified so that

we could start our work. For my first exhibition in 1972, I depicted

Ichari Shahar (Baku's medieval Inner City).

In my private collection of art, I created works related to history,

legends and customs. But it was impossible to exhibit them. Only

my relatives and friends saw them. I didn't hide them, nor do

I think anyone would have arrested me if they had seen them.

We didn't have any restrictions as to what themes we could choose.

You could paint or draw anything. You could even bring the works

to an exhibition, but they simply wouldn't be exhibited. I sensed

which works to take to the exhibition and which not to take.

To tell you the truth, the works I paint today would definitely

have been excluded from the exhibitions.

His Approach

I've loved to read since

childhood. When I decided to become an artist, I wanted so much

to have my art appear in books. I think books, especially children's

books, bear a lot of similarities to miniature art. Children

like to read books with pictures. Since I inject national spirit

into the works that are introduced into children's books, this

helps to foster national spirit within children. I've loved to read since

childhood. When I decided to become an artist, I wanted so much

to have my art appear in books. I think books, especially children's

books, bear a lot of similarities to miniature art. Children

like to read books with pictures. Since I inject national spirit

into the works that are introduced into children's books, this

helps to foster national spirit within children.

As a book illustrator, it's critical for me to transfer the spirit

of each book into its graphics. It's not fair to take anything

away from the general spirit of the book. But when I create other

works on my own, I try to contribute my own ideas and imagination.

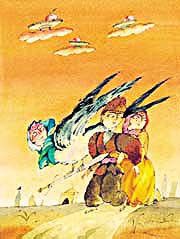

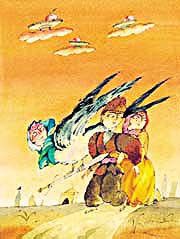

Left: Nusrat Hajiyev, "Malikmammad", 6.25"

x 9", watercolor.

When I work on something, I try to inject my love into it from

the bottom of my heart. I'm known for being very exacting and

paying very close attention to detail. For instance, sometimes

it takes me two hours just to draw a character's beard.

In terms of adding perspective, I try to make the scene convincing.

That is, those who study my works can identify two schools in

them: both the school of miniatures and

the school of contemporary art. I don't draw my figures with

narrow eyes as they did in the past, simply because our people

do not have narrow eyes. I think the artist has the responsibility

to portray life from his own point of view. Why should art remain

like it was in the past?

I love humor and really

enjoy being around people who have a sense of humor. That's why

I try to add a touch of humor to my miniatures as well. I think

humor is inseparable from intelligence. The themes I deal with

primarily are authority and nationality. Such issues are eternal.

They existed in the past, we experience them in our everyday

lives today and they will exist in the future. I love humor and really

enjoy being around people who have a sense of humor. That's why

I try to add a touch of humor to my miniatures as well. I think

humor is inseparable from intelligence. The themes I deal with

primarily are authority and nationality. Such issues are eternal.

They existed in the past, we experience them in our everyday

lives today and they will exist in the future.

But it's not always easy to portray works from a historical point

of view. Finding resources and references to draw the old costumes

turns out to be quite difficult. There are some traditional costumes

on exhibition at the Tagiyev History Museum, but this is not

enough. My primary source comes from ancient miniatures. I've

also found some books and postcards for references. Most artists

have to resort to their own imaginations. It's difficult to create

old settings, but I think it's important to be as authentic as

possible.

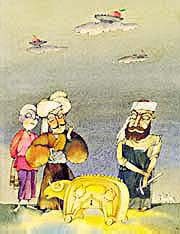

Left: Nusrat Hajiyev, "The Tale of Yusif", 6.25"

x 9", watercolor.

If you look

at the works I did 20 years ago and compare them to what I do

now, you'll see a big difference. Sometimes it's hard for me

to even recognize my own works. Sometimes I don't even want to

remember how I used to draw because I have such a temperament

that usually after finishing a work, the very next day I don't

like it and start being critical of it.

Independence

Even though we have

gained our independence, I don't think I will ever be able to

feel completely free. In fact, I don't want to be free of all

responsibilities. I am not living alone somewhere, isolated on

an island. I have my relatives and my children, and to a certain

extent, I depend on them as they do me. To be independent from

a repressive government is a different issue, but moral dependence

is necessary for mankind. We need our families, our children,

our friends and our art. There can be no such thing as freedom

here on earth. If such a thing could exist, man would be spoiled

spiritually. I like the fact that I need to depend on someone

and that I have specific duties towards them. When I fulfill

these duties, I am the happiest man in the world. The same can

be said about art. I am a human being and I am an artist. They

are dependent on each other. When these two notions merge, they

create something unique indeed. Even though we have

gained our independence, I don't think I will ever be able to

feel completely free. In fact, I don't want to be free of all

responsibilities. I am not living alone somewhere, isolated on

an island. I have my relatives and my children, and to a certain

extent, I depend on them as they do me. To be independent from

a repressive government is a different issue, but moral dependence

is necessary for mankind. We need our families, our children,

our friends and our art. There can be no such thing as freedom

here on earth. If such a thing could exist, man would be spoiled

spiritually. I like the fact that I need to depend on someone

and that I have specific duties towards them. When I fulfill

these duties, I am the happiest man in the world. The same can

be said about art. I am a human being and I am an artist. They

are dependent on each other. When these two notions merge, they

create something unique indeed.

Left: Nusrat Hajiyev, "The King and the Blacksmith".

New Challenges

Before Azerbaijan's independence, it was difficult to consider

most artists who had gained strong reputations as "real

artists". If the situation hadn't changed, no one would

have known about Azerbaijan's talented dissident artists like

Javad Mirjavad [page 30] or Kamal.

Among their peers, they

were very respected, but among the general population, very few

people knew them. No one even looked at them when they walked

down the street. Meanwhile, the well-known artists who catered

to the government's wishes were given the choice assignments,

held high positions and made decisions about art projects (and

who received the commissions and projects). Among their peers, they

were very respected, but among the general population, very few

people knew them. No one even looked at them when they walked

down the street. Meanwhile, the well-known artists who catered

to the government's wishes were given the choice assignments,

held high positions and made decisions about art projects (and

who received the commissions and projects).

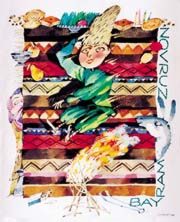

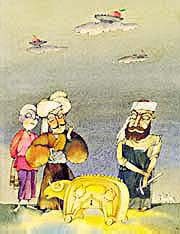

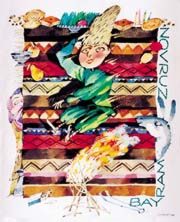

Left: Nusrat Hajiyev, "Jumping Over the Bonfire at Noruz"

(Spring Solstice, March 21).

Today the situation is much different. We used to be dissatisfied

in the past; it wouldn't be fair to say that we are dissatisfied

today. We aren't, but yet we are. It's just that we have a different

set of difficulties that we have to deal with. It's hard for

average artists to make a living. One needs to be world-class

and extremely talented to become well known. The main problem

now is financial. I'm not talking about buying clothes and things

like that. Sometimes I have to be concerned whether I will even

be able to afford paint.

Still, I think art will continue here in Azerbaijan despite the

difficult economic situation. It's something that can't be stopped.

I remain optimistic about this. In the future I think there will

be fewer artists. Very few parents will urge their children to

become artists. But if a child is born with talent, that talent

will emerge. As a result, in the future, I think the quantity

of works will decrease while the quality increases.

Nusrat Hajiyev

can be reached at (99-412) 492-15-90 (home) or 476-17-38 (studio).

He has been a member of Azerbaijan's Artists' Union since 1978.

From

Azerbaijan

International

(7.2) Summer1999.

© Azerbaijan International 1999. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 7.2 (Summer 99)

AI Home

| Magazine

Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|

Visit AZgallery.org for more works of

Visit AZgallery.org for more works of  Of

course, I've had many kinds of artistic influences in my life.

My father Suleyman was an architect who was involved with the

theater and occasionally played the role of an artist in plays.

He also made drawings. Elchin Mammad [a distinguished illustrator]

is my relative. The famous Azerbaijani composer Fikrat Amirov

[1922-1984] was my uncle [See Winter 97, AI 5.4]. I also had

an aunt who was an actress. So I became an artist because I realized

there was such a profession, thanks to the people who were part

of my everyday life.

Of

course, I've had many kinds of artistic influences in my life.

My father Suleyman was an architect who was involved with the

theater and occasionally played the role of an artist in plays.

He also made drawings. Elchin Mammad [a distinguished illustrator]

is my relative. The famous Azerbaijani composer Fikrat Amirov

[1922-1984] was my uncle [See Winter 97, AI 5.4]. I also had

an aunt who was an actress. So I became an artist because I realized

there was such a profession, thanks to the people who were part

of my everyday life.