|

Winter 1997 (5.4)

Page

25

Leyli and Majnun

- 90th Jubilee

The Opera

that Shaped the Music of a Nation

by Ramazan

Khalilov

On January 12, 1908,

it will be 90 years since the premiere of Uzeyir Hajibeyov's

opera, "Leyli and Majnun." Azerbaijanis take pride

that this was the first opera, not only in Azerbaijan, but in

the entire Muslim world. Furthermore, this was the first work

by an Azerbaijani composer to incorporate traditional Azerbaijani

mugam (modal) improvisations into the format of a European opera. On January 12, 1908,

it will be 90 years since the premiere of Uzeyir Hajibeyov's

opera, "Leyli and Majnun." Azerbaijanis take pride

that this was the first opera, not only in Azerbaijan, but in

the entire Muslim world. Furthermore, this was the first work

by an Azerbaijani composer to incorporate traditional Azerbaijani

mugam (modal) improvisations into the format of a European opera.

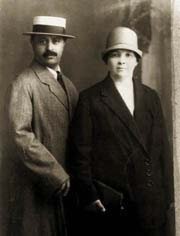

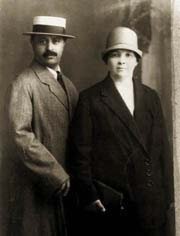

Left: Uzeyir Hajibeyov and

his wife Maleyka in 1926.

"Leyli and Majnun" is a tragic love story based on

the 16th century poem of the same name by the Azerbaijani poet

Fuzuli. The story has its roots in a feudal Arabic legend.

Only one person in Baku is alive today who witnessed that historical

presentation in 1908. Ramazan Khalilov was seven years old at

the time. Here he reminisces about that eventful night that took

place almost a century ago.

Ninety Years Ago

I was

seven years old when the opera "Leyli and Majnun" was

performed for the first time in Baku. I'm Chechen and was born

in Grozny in 1900. My relation with Uzeyir

Hajibeyov began through friendship,

but later on, he married my aunt Malika Teregulova, my mom's

younger sister.

My two uncles, Ali and his older brother Hanafi Teregulov, had

become good friends with Uzeyir when they studied together in

Gory Seminary in Tbilisi [Georgia] at the turn of the century.

Both of them participated in this opera, and that's how I got

involved. Ali directed the orchestra and played violin. Hanafi

led the choir and played the role of Nofar, the military leader,

who protected Majnun. Sometimes they would take me along to rehearsals.

Of course, I was so young at the time that I didn't fully realize

the importance of what was happening. Uzeyir bey (that's the

polite term by which we used to call him) had promised that if

I worked hard at school, I could come to the opening performance

at the Taghiyev Theater. This theater, the first ever built in

Baku, was sponsored by the oil baron Zeyn-al-abdin Taghiyev and

built in 1880. It had an orchestra pit and was designed to accommodate

both musical and dramatic works. The building was down close

to the sea on the site where the new Music Comedy Theater is

currently being built.

On the night of January 12, 1908, I remember that the theater

was full. My mother and my aunts and relatives had come from

Tbilisi for the occasion. The play was scheduled for 7 o'clock

at night. The theater was one of the few buildings enjoying electric

lights. Of course, people arrived on foot or by horse and carriage.

|

Left: Ramazan Khalilov, 97, who saw Azerbaijan's

first opera as a 7-year-old child. He was the Director of the

Hajibeyov Memorial Home Museum until 1999 when he died. Photo:

Blair, 1995.

|

I remember having

to sit with my mother up in the women's gallery. At that time

women were not allowed to appear in public unless they were veiled.

And they weren't allowed to sit in the same assembly hall together

with men, even their own husbands. The main floor was reserved

for men. Women had to sit in reserved boxes on the second and

third levels. Curiously, there was a thin veil-like screen, something

like a fisherman's net, hanging over the gallery that made the

women invisible from the rest of the audience. Needless, to say,

it also obscured their vision of the stage.

I remember pestering my mom alot that evening. Mostly, I was

bothered by the black netting. I couldn't see the stage very

clearly, and I kept asking my mom questions about the plot. Remember,

we didn't grow up with television or radio or theater like kids

do today, and so the story unfolding on stage seemed real.

I really liked the Majnun character. It was played by Huseingulu

Sarabski. He became insane from his love for Leyla. At the final

scene Majnun comes to Leyli's grave, wearing ragged clothes.

He was so distraught and exhausted that he couldn't even recognize

his relatives. As the poem goes, even the animals shared his

grief. And then he died beside Leyli's grave.

I remember being so deeply effected by that scene that I had

wanted to cry. But my father had taught me that mountain men

don't cry. My mom tried to comfort me by telling me that it was

just a story and that I shouldn't worry-Majnun was really all

right. After the opera was over, my family hung around for awhile,

waiting for some of the performers. I saw Sarabski again. He

was really all right. Nothing was wrong with him and so I calmed

down.

Behind the Scenes

Husein

Arablinski directed the opera. Hajibeyov himself was in the orchestra

pit, playing violin that first night. Gurban Primov played tar,

accompanying the mugam singers, and Abdul Ahverdiyev conducted

the orchestra. Ahverdiyev was a famous writer and scriptwriter

from Shusha [a city in Karabakh which is now under military occupation

by Armenians]. Ahverdiyev had written a stage version of "Leyli

and Majnun" that Hajibeyov had seen ten years earlier as

a 13-year-old boy. Actually, the idea to write an opera using

Azerbaijani literary themes and musical motifs came to Hajibeyov

when he was studying at Gory Seminary in Tbilisi. It was there

that he had had the chance to see Rossini's Italian opera"Barber

from Seville."

One of the unique aspects of the performance is that Hajibeyov

used traditional Azerbaijani mugams in their original form-in

the unwritten form-within the opera. But he insisted that the

mugam singers base their text on the poetry of Fuzuli's original

poem. Many of the opera's lines were identical to the original

poetry.

Although choral singing was not an Azerbaijani tradition, Hajibeyov

created a choir to comment on the events developing in the plot,

to make it more dynamic and to emphasize the psychological state

of the characters. It was the first time a choir had been used

in Azerbaijan.

Hajibeyov viewed the opera as a success. He felt that the public

was hungry for a dramatic enactment of a classic scene with folk

music. He also credited Sarabski who was so artistic in his portrayal

of Majnun.

Hajibeyov used to talk about the difficulties they had to overcome

in staging "Leyli and Majnun." There were lots of problems-both

financial as well as creative. At that time, there was no serious

performing culture-no professional actors or singers. It wasn't

easy to find individuals who could perform the lead roles.

Actually, Hajibeyov discovered Sarabski quite by chance. Not

far from the hotel "Tabriz," where he was staying,

was a water distribution center. Hajibeyov often passed by, and

one day he realized that the young man who worked there loved

to sing. In the evenings after work, that young man, Huseingulu

Sarabski, was actively involved with dramatic groups. So Uzeyir

offered him the role of the main character, Majnun. It turned

out to be a very successful choice.

The Female Role

But

selecting someone to play Leyli, the female lead, was more difficult.

Religious authorities had complained about Muslim men singing

on stage. They were even more adamant against women. Muslim women

simply could not appear on stage. Of course, Russian women living

in Baku didn't fall under the same restrictions, but none of

them could sing mugams (traditional modal music) in the Azeri

language. So an Azerbaijani man had to be found to play Leyli's

part.

As the story goes, one day Hajibeyov, Sarabski and Arablinski

were sitting together in a "chaykhana" (tea house)

when a tall, good-looking waiter came over to their table and

brought them tea. He just happened to be singing. That's when

they decided to broach the possibility of his playing the woman's

role, Leyli. After a great deal of persuasion, he finally consented.

His name was Abdulrahim Farajev. So he dressed up as a woman

and took the female lead in the first performances of Azerbaijan's

first opera.

There were other difficulties as well that related to the inadequacy

of props and financial arrangements. Hajibeyov complained that

he had had to sell his opera for a small pittance, and the fact

that the hall was filled night after night brought him no additional

financial benefit.

But more importantly, because of the popular success of the work,

the opera not only secured a place in the annals of the cultural

history of Azerbaijan for the young 23-year-old composer, but

it also set the precedent in Azerbaijan for synthesizing eastern

and western techniques and styles in much of the composed music

that came to be written during the century that followed.

It wasn't until after the Soviets seized power in the 1920s that

women could appear in public without wearing veils. Even today

there are statues in Baku that commemorate this event.

Hajibeyov himself was very sensitive to the issue. The story

is told that even when he was four years old, he used to complain

to his mother about the veil that she had to wear. He would say,

"Mom, you're so pretty. Why do you cover your face with

that rag?"

Hajibeyov later went on to write several music comedies that

satirized this social custom, the most famous of which was "Arshin

Mal Alan" (Cloth Peddler). In his play, the protagonist,

a rich merchant, had everything he wanted in life except the

chance to choose his own bride as all the girls on the street

were fully veiled. He then decided to disguise himself as a cloth

peddler just to gain entrance inside the courtyards to see the

pretty girls and choose one as his wife.

Ramazan Khalilov,

97 (born December 27, 1900), served as Deputy Assistant when

Uzeyir Hajibeyov was the Director of Baku's Conservatory of Music.

He became the "executor of Hajibeyov's will" after

the composer died in 1948 of complications related to diabetes.

Thanks to Ramazan's enormous efforts, the Hajibeyov Memorial

Home Museum was opened in 1975. He has been its Director ever

since. Ramazan died in 1999.

Elmira Abbasova, Professor and former Director of the Music Academy,

also contributed to this article.

From

Azerbaijan

International

(5.4) Winter 1997

© Azerbaijan International 1997. All Rights Reserved.

Back to Index AI 5.4 (Winter

1997)

AI Home |

Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|