|

Spring 2006 (14.1)

Pages

58-71

Kolyma

Off to the Unknown

Stalin's Notorious Prison Camps in Siberia

by

Ayyub Baghirov (1906-1973)

Arrested in 1937, sentenced under false

charges in 1939 to eight years of corrective labor in Kolyma.

In reality, he was in exile for 18 years as he was not released

until 1955, two years after Stalin's death. Arrested in 1937, sentenced under false

charges in 1939 to eight years of corrective labor in Kolyma.

In reality, he was in exile for 18 years as he was not released

until 1955, two years after Stalin's death.

Author of "Bitter Days in Kolyma" (Gorkiye Dni Na Kolime)

in Russian, which was published in 1999. A shorter version came

out in Azeri in 2001.

Ayyub Baghirov's book, "Bitter Days of Kolyma", was

first published in 1999 in Russian as "Gorkiye Dni Na Kolime".

To our knowledge, it was the first personal narrative by an Azerbaijani

author about his years spent in exile in the notorious prison

system of Kolyma located in Siberia's unbearably cold landscape.

The author Ayyub Baghirov (1906-1973) had been the Chief Financial

Officer for the BakSovet (Mayor's office). In 1937, he was arrested

on false charges of anti-revolutionary activities as an "Enemy

of the People". Kept in Baku's notorious NKVD prison, he

was interrogated and tortured for nearly a year and a half before

being sentenced to eight years in a hard labor camp. Unfortunately,

the eight years stretched into 18 years, as was true for many

prisoners. He was not released until 1955, two years after Stalin's

death. He returned to Baku.

Sadly,

Ayyub did not live to fruits of his careful analysis of those

difficult years published. His book came out almost 25 years

after his death. We have his son Mirza to thank for the enormous

job of editing and publishing this personal glimpse into the

Kolyma camps and for providing us with his father's insights

about life under such unbearable situations. Sadly,

Ayyub did not live to fruits of his careful analysis of those

difficult years published. His book came out almost 25 years

after his death. We have his son Mirza to thank for the enormous

job of editing and publishing this personal glimpse into the

Kolyma camps and for providing us with his father's insights

about life under such unbearable situations.

We publish the first chapter here. Chapter I: Arrest. Journey

To the Far North: Butigichag Camp (pages 5-50). Translation from

Russian by Aysel Mustafayeva, editing by Betty Blair.

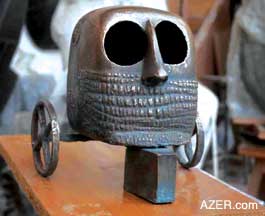

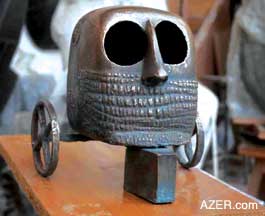

The thought - provoking sculpture shown here was created by Azerbaijani

artist Fazil Najafov (1935- ). Though Fazil was not repressed

himself, he was born during the years when the purges were so

prevalent. To read more about his works in Azerbaijan International,

see "Frozen Images of Transition," (AI 3.1 (Spring

1995). Also "The Expressive Magnificence of Stone,"

AI 7.2 (Summer 1999). Search for both articles at AZER.com. For

more samples of Fazil's works and 170 other Azerbaijani artists,

visit AZgallery.org. Contact Fazil Najafov: Studio: (994-12)

466 -7109, Mobile: (994-50) 342-8999.

Nagaev Bay

One dark cloudy day in late autumn 1939, a steamboat named Dalstroi

[One of many ships that were used especially in the 1930s-40s

to transport tens of thousands of slave laborers to Magadan and

on to the Kolyma camps in the Far North East of Russia] entered

the Nagaev Bay [In Magadan in the Sea of Okhotsk is where the

ships docked so prisoners to disembark on their journey to Kolyma.

The bay and Nagaev Port are named after Russian hydrographer

and cartographer Admiral Aleksei Ivanovich Nagaev (1704-1781)].

A cold

wind was blowing. The large boulders along the coast appeared

as dark foreboding shadows. The nearby hills were already covered

with the first snow. The place had an eerie silence about it.

Where were the usual sounds characteristic of port life and a

residential bay town? A cold

wind was blowing. The large boulders along the coast appeared

as dark foreboding shadows. The nearby hills were already covered

with the first snow. The place had an eerie silence about it.

Where were the usual sounds characteristic of port life and a

residential bay town?

Left: In memory of the victims of World War

II, 25 years later, by Azerbaijani sculptor Fazil Najafov, 1965.

Contact Fazil at his studio: (994-12) 466-7109, Mobile: (994-50)

342-8999.

Many passengers were on board - people of various fates, professions

and ages from all corners of our vast country. And then, there

were us southerners [Here it means anyone who came from any of

the republics in South Caucasus as well as other republics in

the southern part of the USSR-Turkmen, Kazakhs, Tajiks, Uzbeks,

and Kirghiz] as well.

The majority of passengers were political prisoners - those who

had been arrested for "counter-revolutionary activities"

and charged with Article No. 58 of the Penal Code [Article 58

of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (SFSR) Penal

Code was put into force on February 25, 1927, to arrest anyone

suspected of counter-revolutionary activities. In reality, it

was a "catch-all phrase" that enabled authorities to

arrest anyone and bring criminal charges against them].

Finally after that difficult trip, we arrived at our destination-Kolyma

[Kolyma is a region in far northeastern Russia. It is bounded

by the Arctic Ocean on the north and the Okhotsk Sea on the south.

Other than Antarctica, its climate is believed to be the most

severe in the world. Under Joseph Stalin's rule, Kolyma became

the most notorious region of the GULAG [Wikipedia].

Millions of prisoners are believed to have passed through Kolyma

working as slave labor]. Upon arrival, many prisoners breathed

more easily, despite the fact that the name "Kolyma"

frightened them. Those who had never been to the North [Siberia]

were troubled the most.We young people didn't have a clue as

to what to expect. We tried to hang close together as much as

possible, and to help those who were exhausted from the long

trip - the elderly and our friends. Our generation had grown

up during the struggle for Socialist reforms in the Soviet Union.

We had been involved in major projects and had coped with the

difficulties of forced collectivism in the villages.

Whenever the Party had beckoned, we had struggled to help in

these situations, sometimes even risking our lives. And now,

after "Ten Victorious Years of Stalin", we ourselves

had been arrested and exiled along with other prisoners to develop

the Far North regions of Eastern Siberia - Kolyma and Chukotka

[The farthest northeast region of Russia, on the shores of the

Bering Sea. The region was subject to collectivization and forced

settlement during the Soviet Era. It has large reserves of oil,

natural gas, coal, gold, and tungsten [Wikipedia. Wikipedia entries

were quoted from April 15, 2006].

We political prisoners knew that we really were not "Enemies

of the People", nor enemies of the Soviet government. Even

in the white wilderness of the Kolyma camps - dying from hunger,

cold, slave labor, tortures and illness - most of us still didn't

have any idea why we had been brought out here to die.

Youth

Actually, our situation was quite ironic. After the continuous

years of brainwashing that had influenced us as children and

citizens of Soviet republics, we had tried to forget the bad

things that were happening to us personally and devote our energy

to the common interests of our Homeland. Most of us had been

educated in the spirit of true Stalinism: first came the Party,

then Homeland, and only after that came family - mother, father

and children.

We had been fed the official line and indoctrination of the Party

about Komsomols and the Soviet Union being "the most just

community in the world". We had been educated in this way

from childhood as Pioneers [A mass youth organization for children

ages 10-15 that existed in the Soviet Union between 1922 and

1990 [Wikipedia]. I also considered myself innocent. All my life

I had lived under Soviet authority and served this power and

authority with all my strength and belief.

I was born in the city of Lankaran [A city located near Azerbaijan's

southern border with Iran] in Azerbaijan [around 1906]. I wasn't

even a year old when I lost my father Hazrat Gulu. He had been

a rather wealthy merchant. After the Revolution [Refers to April

1920 when the Bolsheviks took control of the power in Azerbaijan]

- from early childhood onward - I grew up in poverty and deprivation.

My mother didn't know how to manage her husband's property.

Being rather trustful and naïve by nature, she soon was

hounded by enterprising relatives and soon ended up on the brink

of poverty. She never did figure out how her material wealth

had slipped through her fingers.

As a child during the years that followed the Revolution, I used

to peddle Ritsa cigarettes on a little tray that hung from around

my neck. I would wander through the narrow lanes of Lankaran.

Career in Finances

My first real job was that of an accountant in the Lankaran Regional

Finance Department. At the beginning of 1930, I came to Baku

and soon was promoted to the position of Manager of the Baku

Finance Department. Later on, I was appointed as a member of

Presidium of BakSovet [BakSovet (via Russian-Bakinskiy Sovet)

meaning the Council of Baku, the Mayor's office], and confirmed

as a member of People's Commissariat of Finance USSR on December

31, 1936, by the decision of SovNarKom [SovNarKom (via Russian-Sovet

Narodnikh Commissar) meaning Council of People's Commissars.

After 1946 the title was changed to Council of Ministers] which

bore the signature of V. M. Molotov Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov

(1890-1986). Soviet politician and diplomat, was a leading figure

in the Soviet government from the 1920s, when he rose to power

as a protégé of Joseph Stalin, to the 1950s, when

he was dismissed from office by Nikita Khrushchev [Wikipedia].

Whatever assignment I was ever given, I was very conscientious

to fulfill my responsibilities.

Above: Shipping routes in the Arctic used

to bring prisoners to the Kolyma forced labor prison camps.

It was especially difficult for anyone working in the field of

finances during the period of collectivization when the villagers

had to give up their land, their animals and property. In addition

to such demands, the government imposed artificial loans that

totally bankrupted the peasant economy. The government applied

every known method to squeeze and suppress farmers.

Baku's German Church

I'll never forget an ordinance related to the closure of the

German Protestant Church [German Protestant Church. This church

still stands today and is familiarly known as "kirka",

the German word for church. The Nobel Brothers in Baku donated

some of the funds to construct this chapel. Fortunately, during

the Soviet period, this church was not destroyed although many

others were. Instead, the building, which houses a pipe organ

and has outstanding acoustics, was converted into a music concert

hall] in Baku. It was quite a remarkable building in the center

of town located on Telephone Street [now 28th of May Street]The

28th of May Street is named to commemorate the date of Independence

of Azerbaijan, when it won its independence over the Russian

Czar in 1918. This day is still commemorated today after Azerbaijan

regained its independence from the Soviet Union, though the declaration

of independence from the Soviet Union is officially August 30,

1991]

Both the government and the NKVD [NKVD: Russian for Narodniy

Komissariat Vnutrennikh Del (People's Commissariat for Internal

Affairs) was a government department which handled a number of

the Soviet Union's affairs of state. It is best known for the

Main Directorate for State Security (GUGB), which succeeded the

OGPU and the Cheka as the secret police agency of the Soviet

Union and was followed by the KGB. The GUGB was instrumental

in Stalin's ethnic cleansing and genocides, and was responsible

for massacres of civilians and other war crimes. Many consider

the NKVD to be a criminal organization, mostly for the activities

of GUGB officers and investigators, as well as supporting NKVD

troops and GULAG guards] tried various tactics to close down

the church. At first, they claimed that the churches were hotbeds

of anti-Soviet thought. Then they spread rumors that the priests

and some of the parishioners were German agents.

Finally, early in 1937, the All-Union Prosecutor A. Y Vishinskiy

got involved and solved the problem once and for all by obliging

the financial organs to assess the German church with such a

huge tax bill that they were not be able to pay. The church soon

had no choice but to close its doors.

Encounter with

Mir Jafar

In regard to my own arrest, I always suspected that there had

been a link between my responsibilities related to financial

affairs that caused Mir Jafar Baghirov [Mir Jafar Baghirov: Secretary

of the Communist Party for Azerbaijan, who served as Stalin's

"right hand man" in Baku] - the tyrant of the republic

- to order my arrest.

However, the NKVD arrested me and officially accused me of "participating

in an anti-Soviet organization". One day in autumn 1937,

Mir Jafar Baghirov called me to his office and asked me to check

into the financial affairs of the former representative of the

BakSovet - Arnold Petrovich Olin. You see, even the city officials

were not spared from Stalin's Purges [Stalin's Purges: Term used

for the waves of repressive measures carried out by Stalin, especially

in the 1930s and 1940s. One of the main dates associated with

Stalin's Repressions is 1937; however, there were other dates,

both before and after, which probably resulted in even more deaths.

Millions of people died in Stalin's purges. Many people were

executed by firing squad [actual statistics are unknown but are

estimated to be in the millions], and millions were forcibly

resettled]. Of the 11 members of the Presidium of the Baksovet,

only two of us had not yet been arrested. I was one of them.

Others had already been repressed [Many were imprisoned and tortured

or sent to labor camps, both functioning as part of the GULAG

system. Many died in the labor camps due to starvation, disease,

exposure and overwork. The Great Purge was started under the

NKVD chief Henrikh Yagoda, but another major campaign was carried

out by Nikolai Yezhov, from September 1936 to August 1938, and

others followed. However the campaigns were carried out according

to the general line, and often by direct orders, of the Party

politburo headed by Stalin [Wikipedia].

Left: Pedestal of Kirov's statue on the

highest hill in Baku overlooking the Caspian. Note that the bas-relief

relates to oil drilling. Kirov's statue was dismantled in 1992. Left: Pedestal of Kirov's statue on the

highest hill in Baku overlooking the Caspian. Note that the bas-relief

relates to oil drilling. Kirov's statue was dismantled in 1992.

18 Repressed: Term used to describe the people who were arrested

by government organs, imprisoned, shot or sent into exile. This

term is especially to describe the abuse of power against ordinary

citizens during Stalin's purges. The term "repression"

was officially used to denote the prosecution of people recognized

as counter-revolutionaries and "Enemies of the People".

Purges were motivated by the desire on the part of the leadership

to remove dissident elements from the Party and what is often

considered to have been a desire to consolidate the authority

of Joseph Stalin. Additional campaigns of repression were carried

out against social groups, which were believed or were accused

of to have opposed the Soviet state and the politics of the Communist

Party [Wikipedia].

Olin was also arrested and accused of being an "Enemy of

the People".

Mir Jafar Baghirov gave me one month to check his financial records

and ordered me to provide this summary to him personally. During

our conversation, he mentioned that Olin was a morally depraved

person and that not only had he carried out activities which

were hostile to the government, but that he had accessed the

city's finances for personal use.

After checking the Baksovet financial records, I told Mir Jafar

that I had not discovered any financial violations in that regard.

Mir Jafar interrupted our telephone conversation and started

swearing at me. When there was a pause, I clearly heard him on

another phone addressing the People's Commissar Sumbatov Topuridze:

"Eyyub Baghirov from the Baksovet should be investigated

himself."

I understood only too well what that meant. It was then that

I understood that I was to share the same fate as my colleagues

from the Presidium of Baksovet, along with thousands of other

people who were struggling behind the prison walls of the NKVD.

Mir Jafar Baghirov was a loyal follower of Stalin. In meetings

and gatherings, he used to refer to Stalin as the embodiment

of Lenin. I remember one such meeting that took place in the

Baku Opera Theater. The style and methods of Stalin's administration

were widely introduced in Azerbaijan by Baghirov.

Opposition to any of his plans was severely punished. I remember

the outrageous and sacrilegious decision that Baghirov made to

demolish Baku's oldest cemetery, which is located on the hill

above the bay[Cemetery: After Black January 1990 when Soviet

troops attacked civilians in Baku in an effort to squelch the

independence movement in Azerbaijan, the area that once had been

set aside for Kirov Park was used to bury Black January victims.

Today the cemetery is known as "Shahidlar Khiyabani"

(Martyrs' Cemetery). Also some victims of the Karabakh war are

buried there. Foreign dignitaries are usually taken to Shahidlar

Khiyabani as part of their official tour in Baku].

In its place, Baghirov proposed that a cultural and leisure park

be constructed and named after Kirov Sergey M. Kirov (1886-1934)

was instrumental in bringing Bolshevik troops to Baku, which

took control of Azerbaijan in 1920. Kirov became the head of

the Azerbaijan Bolshevik Party in 1921. He was a loyal supporter

of Stalin. His rise in popularity aroused Stalin's jealousy.

On December 1, 1934, Kirov was murdered, and it is widely believed

that Stalin ordered his death, although this has never been proven

[Wikipedia]. And that's exactly what they did. They even made

us - the workers of BakSovet - work as subbotniks [Russian for

unpaid voluntary work done on Saturdays] to construct the park.

Above:

The Kirov Amusement park

which Eyyub Baghirov complained about as it was originally a

cemetery. Only after Black January 1990 was it converted back

to a cemetery, today known as Cemetery of the Martyrs (Shahidlar

Khiyabani). Mir Jafar Baghirov, Stalin's right hand man in Azerbaijan

had created the park in the 1930s.

Once I expressed some doubts about the feasibility of the construction

of the park from a financial point of view. Immediately after

that, I was kicked out of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan.

Arrest

And then the inevitable happened. I didn't have to wait long.

In the early morning hours of December 22 ["Black Ravens":

The government's notorious black cars, which were used to arrest

suspects, often on false charges of being "Enemies of the

People". These "political criminals" were usually

imprisoned, sent into exile or executed. Surprise arrests were

often made in the wee hours of the morning. See the painting

by Boris Vladimirsky (1878-1950) on the front cover of Azerbaijan

International magazine, AI 13.4 (Winter 2005). Also read the

short story, "Morning of that Night", by Anar in Azerbaijan

International AI 7.1 (Spring 1999). Search for both articles

at AZER.com.], 1937, three NKVD agents came knocking on my door.

The fourth agent was waiting in the street beside one of those

cars - a "Black Raven".22 I understood that my turn

had come. I had just returned from an official trip to Moscow

where I had participated in the Annual People's Commissariat

of Finances.

Two NKVD agents went looking through all my stuff in the apartment,

while the third one was writing a protocol about the search.

The guard from the courtyard was called as a witness. He sat

in a chair in the hall entrance. The search was just a formality

for the agents knew in advance that they would find nothing of

interest.

During the search, I naively asked why I was being arrested.

One of the agents answered that I could speak with the People's

Commissar of Internal Affairs and maybe I would be sent back

home. I was told to take some warm clothes with me - woolen socks

and sweaters.To me, this was a sign that I would be taken away

for a long period of time. Then I remembered the telephone conversation

that I had had with Mir Jafar Baghirov. Such an encounter could

not be easily dismissed.

Although it was winter, the sun was already up. As I was led

out the door, I told my family: "Always remember that I'm

not guilty of anything." At that moment, my niece Bilgeyis,

who was living with us at the time, started crying. Deep within

me, I genuinely believed that everything that was happening was

some kind of misunderstanding and that I would be released immediately.

Obviously, thousands of innocent people had thought the same

thing.

Baku's NKVD Prison

The streets were still empty as we drove through the city. Slowly,

our Black Raven passed through massive steel gates of the NKVD

Building down near the seafront[NKVD building in Baku, located

on the corner of Rashid Behbudov Street and Azerbaijan Avenue,

was originally a building constructed during the Oil Baron period

and today in use as State Frontier Services (Dovlat Sharhad Khidmati)].

Above: Sculpture: Blind Men by Fazil Najafov,

bronze. Above: Sculpture: Blind Men by Fazil Najafov,

bronze.

Most Baku residents knew the administrative building of the

NKVD Azerbaijan as a building of three stories.

But the exterior of the building hid the existence of another

building inside the courtyard - which was the actual prison itself

and consisted of four floors with quite thick walls and barred

windows. In the courtyard, there was a steam plant, which provided

the building with its own source of electricity.

There was also a garage. On the first floor of the prison there

were adjunct buildings, such as toilets, showers and a guards'

room. The rooms in the basement had originally been used as wine

cellars before the Revolution [Pre-revolutionary times: This

refers to the Oil Baron days in Baku prior to the Bolshevik takeover

in April 1920] and stretched far out beneath the sea.

Now those cells were used as torture chambers. On both sides

of the long prison corridors were rows of cells that held 10,

20 or more prisoners.

Because there were many arrests in 1937-1938 in Azerbaijan, the

prisons were full... The cells were typical. They had concrete

floors. There was a little window in the door through which food

could be passed. A dim light bulb hung from the ceiling. A small

hole on the door was covered with a leather cloth so that the

prisoners could be watched. The cell windows - approximately

30 x 40 cm - usually opened to the courtyard.

On the second floor, the barred windows were completely covered

with metallic louvers so that sun could not shine in; it was

impossible to see even a small patch of sky. The rooms, which

had windows overlooking the courtyard, were used as offices for

the investigators.

|

"Always remember

that I'm not guilty of anything,' I told my family as I was led

out the door. Deep within me, I genuinely believed that everything

that was happening was some kind of misunderstanding, and that

I would be released immediately. Obviously, thousands of innocent

people had thought the same thing."

-Ayyub Baghirov

"Bitter Days of Kolyma"

|

During those years of mass arrests, armed soldiers were posted

along the streets near NKVD building. The government did everything

possible to prevent prisoners from escaping from this - the cruelest

of buildings. There was no possibility to escape. They were determined

to prove your guilt by any means possible. Later I learned from

my cellmates that executions took place in the basement of the

NKVD building, as well as on Nargin Island in the Caspian not

far from Baku. No one lived on that island; therefore, there

were never any witnesses to these crimes. No one but the executioners

ever heard those shots.

Artificial Charges

Against Me

As for me, I was accused of participating in an anti-Soviet organization,

which was headed by A. P. Olin, representative of the Baku Council.

Latvian by nationality, he had been member of the Party since

1918. He had worked as a Latvian Arrow guarding the Kremlin.

He had also worked in the political departments of Central Asian

and Transcaucasian regions. From 1931 to 1934, he had worked

as Secretary of the Transcaucasian region on the Committee VKP,

which was responsible for transportation and supplies.

From 1934 to 1936 he had been the representative of Transcaucasia

near SovNarKom USSR, and lived and worked in Moscow. In 1936

he had been transferred to Baku, and from July served as Representative

of the BakSovet [City Hall]. In the autumn of 1937, he was arrested

and sent back to Moscow. They executed him in Tbilisi.

I had known Olin as a co - worker at BakSovet for only a few

months. He was not a very social person. I found him to be serious

and conscientious about his work.

Left: Family by Fazil Najafov, bronze Left: Family by Fazil Najafov, bronze

Later on, after sitting

behind the walls of NKVD Azerbaijan, I understood that Mir Jafar

Baghirov and Sumbatov - Topuridze had wanted to get additional

damning material against Olin. So I had been arrested as a member

of an imaginary counter - revolutionary, anti - Soviet organization

of which Olin was supposedly leading. I had been implicated simply

because I was his co-worker.

Interrogations began three or

four days after my arrest. They were carried out by Kh. Khaldibanov.

The first question during each interrogation was an attempt to

reveal how Olin had involved me in his anti - Soviet organization

- the main goal of which was to destroy the Soviet power, restore

capitalism, and even revive various activities of market economy.

The accusations against me were absurd. A wide range of people

had accused me - some of whom I didn't even know.

In the non-existent, counter-revolutionist organization of which

I, supposedly, was a member, there were 20 other members. There

were people of different ages and professions, working at different

institutions and enterprises, many of whom were employed in the

BakSovet, or regional committees of the party, executive committees,

oil sectors, construction and supply organizations.

I felt like a small pawn in a political game being played out

by Mir Jafar Baghirov and Sumbatov - Topuridze, in which they

tried to gather the most vicious evidence about administrative

workers of republic and BakSovet. Based on the deposition that

they extracted by torturing Olin and his deputy Kudryavtsev who

had been arrested prior to me, the interrogator threatened me

with torture if I would not reveal the specific date (supposedly

the end of March 1937) when I had joined this fictional anti-Soviet

organization.

I remember once being brought to meet with Sumbatov - Topuridze,

who demanded: "Confirm that you were a member of the Olin's

organization and we will release you". When he didn't get

the answer that he wanted, he punched me in the face. That day

I was made to stand in my cell for more than 24 hours. When I

collapsed, they beat me unconscious. Many times, they took me

down to that dark, humid basement, and threatened to shoot me.

Then they would bring me back upstairs to the main cell.

Sitting there in the underground cells of the NKVD, eventually

we learned how to tap out on the thick stone walls what came

to be known as the "alphabet of prisoners" [The "alphabet

of prisoners" refers to a system of tapping out code on

the prison cell walls, enabling the isolated prisoners to communicate

between each other] to get the latest news and discover who were

the latest victims that had been arrested.

Interrogations

The interrogations took place day after day. To make the accusations

seem to be as true as possible, the interrogator would introduce

new "facts" from those who were arrested regarding

my case. So many times I requested to meet those people, but

the interrogator refused, and no witness was ever called who

could confirm my involvement in any counter-revolutionary activity.

Later on, to make the "case" appear more serious, they

accused me of harboring political motives, "proving"

that I had abused and violated the financial and economic activities

of BakSovet.

They even accused me of artificially reducing and illegally eliminating

debts incurred by the "kulaks" [Kulaks, here, refers

to the relatively wealthy peasants of the Russian Empire who

owned large farms and hired farmhands. They were the class among

the countryside, which were targeted first when the Bolsheviks

took power to be collectivization of the farms] in Lankaran and

the prosperous peasants in Absheron. They said I had covered

up financial crimes of "Enemies of the People" who

had been arrested and prevented new pawnshops from being opened

in Baku in order to infuriate the people against the Soviet power.

|

"Some of our family

and friends gathered at the pier when they learned that we would

soon be shipped out. Our eyes sought out each other in the crowd.

From afar I saw my mother Sughra and daughter Latifa. With tears

in our eyes, we waved goodbye to each other. The guards would

not allow us to go closer."

-Ayyub Baghirov

in "Bitter Days of Kolyma"

|

In reality, during those years of deprivation, people had no

choice but to pawn off their personal belongings in order to

have enough money for basic essentials. Long queues would form

in front of the pawnshops. People would line up the night before

in order to leave some item the next day.

They made such ridiculous claims against me, saying, for example,

that people who were applying for government loans had angrily

complained about some of their problems, and that I, as the financial

officer, had sympathized with them. Moreover, they insisted that

I had expressed my indignation and anger about such issues to

the workers of the Baku City Financial Department.

During the interrogations, I began to realize that quite some

time prior to my arrest, the NKVD had pressured individuals working

in various Soviet organs in Lankaran to denounce me in relationship

to my past, especially since my father had been a wealthy landowner

and owned considerable property. Again, ordered by the NKVD,

BakSovet had written up an accusation against me, claiming that

I had close relationships with individuals who had been identified

as "Enemies of the People".

Appeal to Moscow

Later on, when I arrived at the Kolyma camps and finally got

the chance, I wrote many letters to the head of the country and

to the NKVD about the absurdity of the accusations that had been

brought against me. In one of those letters I even stated that

on the specific date of March 25, 1937, when I had supposedly

been engaged in counter-revolutionary activities organized by

the administrators of BakSovet, Olin as the BakSovet representative

had been in Moscow. His deputy Kudryavtsev had been in Ukraine.

So they had not even been physically present in Baku on that

date.

At times when they threatened me and I would not yield, they

would torture me, beating me with rubber truncheons, and kicking

me with the spurs on their boots, which made wounds that bled.

I still have a scar on my left leg from being kicked by one of

the sergeants. Watching this sadist show while I was being tortured,

the interrogator dared to tell me: "The People's Commissar

ordered us to make 'scrambled eggs' of you." Then there

was the NKVD technique called the "Conveyor Belt" which

was in widespread use. I was brought into a room that was brightly

lit and made to stand although there was a chair available nearby.

They would not permit me to sit.

The

interrogators would repeat the same questions over and over.

They would press me: "It's stupid not to confess. There

are witnesses who have confirmed that you have been involved

in an 'anti-Soviet organization'. You cannot escape these facts.

Tell us the names of other members of your organization and your

punishment will be reduced." The

interrogators would repeat the same questions over and over.

They would press me: "It's stupid not to confess. There

are witnesses who have confirmed that you have been involved

in an 'anti-Soviet organization'. You cannot escape these facts.

Tell us the names of other members of your organization and your

punishment will be reduced."

I insisted that they call witnesses who could support me from

among my close coworkers at the Baku Financial Department but

they wouldn't do it.

Then the next cycle of questions would be repeated while I was

being made to stand there continuously, despite the fact that

the interrogators had already changed several shifts. Finally,

exhausted, I would be taken back to the cell in a semi-conscious

condition.

That is how I passed the time, day after day for more than 18

months in this so-called "preliminary interrogation"

inside the walls of NKVD Azerbaijan. That's nearly 600 days and

nights. The interrogators would change. I had three different

ones. Sometimes they would be a bit softer and would not continue

the interrogations all week long. Sometimes, they left me in

peace, unable to get me to confess to anything.

Above: Map of Kolyma, in the Arctic Circle

in Siberia not far from Alaska. Ships rought prisoners from the

mainland to Kolyma. Much of the year the sea was covered with

sick ice. Prisoners describe the journey as unbearable - the

crowded conditions, lack of hygiene, noise, and lack of load

of food. And then sometimes the sea was very stormy and violent.

Sentence - 8 Years

Labor

Finally, on March 31, 1939, the NKVD case against me was finalized.

I refused to sign it. After that, the case was sent to two other

courts - first, to the special collegium of the Supreme Court

of Azerbaijan, and then to the Military Collegium of Transcaucasian

Military District. I'm sure my case was not really investigated

by either of these courts because it would have been impossible

for them to offer any proof.

But the fate of political prisoners had been decided beforehand.

On June 9, 1939, without even participating in the trial, I was

sentenced to eight years of corrective labor camp "for participation

in an anti-Soviet organization".

On July 1, 1939, I was informed of the court's decision. After

a few days, the long and distant journey to Kolyma began. Somewhere

in the depths of our hearts, we still thought that the Party

would solve everything. And with that hope and belief, we somehow

managed to survive those difficult days.

Kolyma

Let me return to our first days in Kolyma. Obviously, the main

question that we were concerned about was where we were being

taken and what was awaiting us. For us, this enormous, uninhabited

land in northeast Asia with its very cold climate appeared as

a big empty blank space on the map.

Later on, we would learn the names that people had given to this

part of the world: "Black Planet," "Devil's Hell,"

and "Caldron within a Caldron." There was also a famous

song about Kolyma: "Magic planet, where 12 months of the

year are winter, and the rest are summer." Naturally, we

had no idea about the living conditions that we would face.

Above:

The Sakhalin, after being

renamed Krasnoyarsk. It was aboard this ship that Berzin and

150 others arrived in Bleak Nagaev Bay to launch Dal'stroi. Source:

U.S. Navy in Bollinger's Stalin's Slave Ships, Praeger, 2003.

Having now lived there in Kolyma for nearly 20 years of my life,

I know so much about its origins. Its land is rich with rare

metals - especially gold and tin [some people suggest uranium

as well]. Its natural environment is ideal for the development

of reindeer breeding, fishing, the shipping and fur industry,

and for hunting.

Left: "Three Wise Men, Limestone

by sculptor Fazil Najafov, Size: H-68. The sculpture reflects

the climate of secrecy that defined the era. Visit AzGallery.org Left: "Three Wise Men, Limestone

by sculptor Fazil Najafov, Size: H-68. The sculpture reflects

the climate of secrecy that defined the era. Visit AzGallery.org

In the beginning of the 1930s, there was a small town called

Magadan, which would become the center of Kolyma. It consisted

of only a small number of wooden cabins. In 1932, they began

to construct Nagaev Port.

The first houses were situated near the port district. The prisoners

- road workers of the Kolyma camps - built the first roads between

Magadan and the inner regions of the taiga [Taiga is a general

term indicating an ecological region characterized by coniferous

forests. Here it refers to remote, previously unpopulated areas

in northern Russia and Siberia, where many of the slave labor

camps were set up. In such regions, temperatures were extreme,

and varied from -50C to 30C (-58F to 86F) throughout the entire

year, with eight or more months of temperatures averaging -10C

(14F).

The summers, while short, are generally warm and humid [Wikipedia].

They constructed mines, built factories, repair warehouses and

electricity stations. In 1938 there was fewer than 1,000 kilometers

of roads in Kolyma. Roads were built from the sweat of prisoners

with their bare hands and no equipment.

The prisoners worked on roads in all kinds of rugged terrain

- mountain, rivers, canyons, boulders and swamps. After the war,

these roads extended more than 2,000 kilometers. Geologists did

succeed in extracting gold, tin, silver and coal from these extremely

difficult and remote regions.

At the beginning, I was assigned to do strenuous manual labor.

Later on, I worked as a civilian on geologic projects in the

remote taiga. It was there that I met many famous geologists

such as Valentin Aleksandrovich Tsaregradskiy, Boris Nikolayevich

Yerofeev and Izrail Yefimovich Drakin.

I worked under very hard conditions alongside Mark Isidorrivich

Rokhlin, Mikhail Aleksandrovich Chumak, Aziz Khozrayevich, Yevgeniy

Ivanovich Kapranov, Konstatin Aleksandrovich Ivanov, Kiloay Yevdakimovich

Sushentsov, Boris Fedorovich Khamitsayev, Dmitriy Ivanovich Kurichev

and others. I am deeply indebted to many of these people for

their help during those difficult days in my life in Kolyma.

Many years after I was rehabilitated and gained access to KGB

archival documents, I found a description of myself, which had

been written by Mark Isidorovich Rokhlin which read: "Upon

arrival at Kolyma, Comrade Eyyub Hazrat Gulu oghlu Baghirov conducted

himself as a worthy son of his Soviet Nation."

For me to be characterized in such a way during the blackest

period of my life by such an honest person, who was a Doctor

of Mineral Sciences and native of Leningrad, came to mean a great

deal to me during the later years of my life.

Journey by Railroad

On July 4, 1939, we left Baku from Pier 15[Pier 15 has since

been replaced by the "Bulvar" (Boulevard) beside the

sea where there is an accompanying park and restaurants]. We

had been taken there in prison cars from the NKVD building, which

is quite close by the sea. I had been held at the NKVD for more

than a year and a half.

Some of our family and friends gathered at the pier when they

learned that we would soon be shipped out. Our eyes sought out

each other in the crowd from afar. I recognized my mother Sugra

and daughter Latifa. With tears in our eyes, we waved goodbye

to each other. The guards would not allow us to go closer.

We were taken to Krasnovodsk[Krasnovodsk (now called Turkmenbashi)

is a city in West Turkmenistan on the Krasnovodsk Gulf of the

Caspian Sea. It was founded in 1869 and now serves as the western

terminus for oil and natural gas pipelines and for the Trans-Caspian

railroad, which links the Caspian region with Central Asia. It

is also a trans-shipment point for agricultural produce], and

then, after stuffing us into railroad cars, we started to move

forward. We had no idea of our final destination.

The train cars had windows that were barred. Three levels of

shelves had been made out of planks that served as our beds.

There were armed guards who often carried out searches. They

would count and recount us like cattle, making us move from one

side of the wagon to the other.

Sometimes they wouldn't allow us to go to the toilet. Sometimes

prisoners couldn't help themselves and went anyway right there

inside the train. The stench was horrid. We each tried desperately

to get a little extra fresh air through the cracks in the doors.

We passed through Turkib Road, Central Asia, Siberia, Baikal

region [Baikal is a mountainous region near Lake Baikal, the

deepest and oldest freshwater lake in the world. It is located

in Southern Siberia in Russia] and the Far East. The trip took

us four months. The terrible heat, the lack of fresh air, the

unbearable overcrowded conditions all exhausted us. We were all

half starved. Some of the elderly prisoners, who became so weak

and emaciated, died along the way. Their corpses were left abandoned

alongside the railroad tracks.

Often, villagers would toss bread and other foodstuff to us when

they realized that we were prisoners. This happened especially

in Central Asia despite how much the guards tried to keep them

from doing this. Sometimes our railroad cars would be parked

on railroad sidings in uninhabited places so that no one could

approach us.

From talking to one of the guards, we discovered that our final

destination was Magadan [Magadan is a city port founded in 1933

on the Okhotsk Sea in northeast Russia. During Stalin's era,

Magadan was a major transit center for prisoners being sent to

labor camps. The operations of Dalstroi-a vast and brutal forced-labor

gold-mining concern-were the main economic source of the city

for many decades during Soviet times.

The city is very isolated and its climate is subarctic. Winters

are prolonged and very cold, with up to six months of sub-zero

and below-zero temperatures, causing the soil to remain in a

permanently frozen state. Permafrost and tundra cover most of

the region. Average temperatures in the interior range from -38°C

in January to 16°C in July (-36°F to 60°F) Today

Magadan has an enormous Cathedral under construction, and the

Mask of Sorrow memorial-a huge sculpture in memory of Stalin's

victims [Wikipedia]. Though years have passed and many experiences

have intervened, time always has a way of remembering the things

which have pierced the heart.

That daunting prison journey that went on and on for four months

has always remained so vivid in my memory. It's a nightmare that

has stayed with me throughout my life.

We arrived in Vladivostok in the evening and were placed in what

was called a "forwarding camp". This was a large area

surrounded by barbed wire. Inside were small wooden cabins and

tents. Armed guards stood watch. This was our introduction to

Kolyma - the slave-labor empire of the GULAG [nne Applebaum explains

in her 2004 Pulitzer prize-winning book "Gulag: A History"

[Penguin: London, 2004, page 4]: "Literally, the word GULAG

is an acronym, meaning Glavnoe Upravlenie Lagerei, or Main Camp

Administration. Over time, the word GULAG has also come to signify

not only the administration of the concentration camps but also

the system of Soviet slave labor itself, in all its forms and

varieties: labor camps, punishment camps, criminal and political

camps, women's camps, children's camps, transit camps. Even more

broadly, GULAG has come to mean the Soviet repressive system

itself, the set of procedures that prisoners once called the

"meat-grinder": the arrests, the interrogations, the

transport in unheated train cars, the forced labor, the destruction

of families, the years spent in exile, the early and unnecessary

deaths."].

The peak years for arrests were 1937-1938 so there were several

thousand prisoners at this transit camp who had arrived before

us. The majority of them were political prisoners who had been

arrested for "counter-revolutionary activities" and

had been given sentences from eight to 25 years in exile.

The autumn days were sunny, but cold. The stars shone brilliantly

against the dark night sky. This was a sign of hope, and hope

is always the last thing to die. The huge ships moored here so

prisoners could be transported to the vast wilderness of the

taiga and the forestry mills of Kolyma.

Uncle Vanya

They kept us in the transit camp for several days before we could

leave for Magadan. Among the political prisoners, some former

Bolsheviks had also been arrested. I recognized some of them

such as Ivan Vasilevich Ulyanov (Uncle Vanya), Shirali Akhundov,

Armenak Karakozov and Khalil Aghamirov. Here as well, we witnessed

Stalin's practice of targeting people in society who knew the

history of the Revolution and who had strong opinions about such

issues.

The night before we were to sail from Vladivostok to Magadan,

we couldn't sleep. Uncle Vanya, sensing our mood - especially

among the young people - gave us some fatherly advice: "Don't

give up. Be strong in spirit. Brave the difficulties that are

awaiting you. Maintain your devotion to our people to the end,

and show your good work in developing this desolate land."

Uncle Vanya hugged and kissed each of us - his fellow countrymen

- and wished us Godspeed. I had known him since youth when he

had been sent to Lankaran District as Secretary of the Communist

Party Committee during those first years following the Revolution.

We also knew him from Baku, as an official representative of

the Party, a Revolutionist, and a member of the Party since year

1903.

Uncle Vanya spoke with passion and confidence. It reminded me

of a speech he had made in December 1934 when he spoke with so

much concern at the BakSovet regarding the murder of Kirov [Sergey

Mironovich Kirov (18861934) was a Russian revolutionary

and high Bolshevik functionary. He was born Sergey Mironovich

Kostrikov, later assuming the name "Kirov" as an alias.

His alleged 1934 assassination marked the beginning of Stalin's

Great Purges, which removed almost all "Old Bolsheviks"

from the Soviet government. By this time, Sergey Kostrikov had

changed his name to Kirov. He had selected it as a pen name,

just as other Russian revolutionary leaders. The name "Kir"

reminded him of a Persian warrior king, and he was to become

head of the Bolshevik military administration in Astrakhan.

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, he fought in the Russian

Civil War until 1920. In 1921, he became head of the Azerbaijan

party organization. Kirov loyally supported Joseph Stalin, and

in 1926 he was rewarded with the leadership of the Leningrad

party.

In the 1930s, Stalin became increasingly worried about Kirov's

growing popularity. At the 1934 Party Congress where the vote

for the new Central Committee was held, Kirov received only three

negative votes, the fewest of any candidate, while Stalin received

292 negative votes, the highest of any candidate. Kirov was a

close friend with Sergo Ordzhonikidze, whom together formed a

moderate bloc to Stalin in the Politburo. Later in 1934, Stalin

asked Kirov to work for him in Moscow, most probably to keep

a closer eye on him. Kirov refused, however, and in Stalin's

eyes became a competitor.

On December 1, 1934, Kirov was killed by Leonid Nikolaev in Leningrad.

Stalin claimed that Nikolaev was part of a larger conspiracy

led by Leon Trotsky against the Soviet government. This resulted

in the arrest and execution of Lev Kamenev, Grigory Zinoviev,

and fourteen others in 1936. It is widely believed that Stalin

was the man who ordered the murder of Kirov, but this has never

been proven. [Wikipedia].

|

"The terrible heat,

the lack of fresh air, the unbearable overcrowded conditions

all exhausted us. We were all half starved. Some of the elderly

prisoners, who had become so weak and emaciated, died along the

way. Their corpses were left abandoned alongside the railroad

tracks."

-Ayyub Baghirov

in "Bitter Days of Kolyma

|

Due to Kirov's popularity, Stalin took his death as a real tragedy

and buried him by the Kremlin Wall in a state funeral. Many cities,

streets and factories took his name, including the cities of

Kirov (formerly Vyatka) and Kirovograd (Kirovohrad in Ukrainian),

the station Kirovskaya of the Moscow Metro (now Chistiye Prudy)

and the massive Kirov industrial plant in Saint Petersburg (Kirovskiy

Zavod).

For many years, a huge statue of Kirov in granite and bronze

dominated the panorama of the city of Baku. The monument was

erected on a hill in 1939. [Wikipedia: April 28, 2006]. Kirov

came to the Caucasus in 1910 to work as a Communist Party organizer.

Eventually, he helped organize the Red Army's entry into the

Caucasus; they drove out the White Guards in 1920 and subsequently

set up three socialist republics in the region-Armenia, Georgia

and Azerbaijan.

Kirov's statue was dismantled in 1992, after Azerbaijan gained

its independence. On August 26, 1991, the Executive Power of

Baku ordered the dismantling of the statues of Lenin, Kirov,

Felix Dzerzhinski and Ivan Fioletov (all revolutionaries involved

with establishing the Soviet government in Azerbaijan) and the

11th Army, which invaded Baku in 1920. This declaration preceded

Azerbaijan's declaration of independence on October 18, 1991

and the subsequent collapse of the Soviet Union on December 7,

1991.

Baku's Sahar newspaper published the announcement of the statue's

removal on January 5, 1992. Although the article did not mention

the actual date of its dismantling, Sahar's current editor presumes

it must have taken place a day or two earlier, since they were

publishing daily at the time. The bronze used in the statue was

turned over as scrap metal to the Baku City Industrial Center.

See "Best View of the Bay: What Happened to Kirov's Statue"

by Faig Karimov. AI 9.2 (Summer 1999). Search at AZER.com.].

His speech was clear to everyone - regardless of whether they

were uneducated peasants, members of the intelligentsia or religious

fanatics.

I never forgot Uncle Vanya's parting words to us during those

horrible days at Vladivostok. Such wise words coming from such

a great, knowledgeable person instilled us with optimism for

the difficult years ahead that we would face in Kolyma.

Value of Labor

Let me add that along with hope, the main thing that helped us

to survive the Far North was labor. Being actively involved with

work was a necessity of life in the severe climate of the North.

Work became a life-saving stimulus for us. Those who understood

this truth from the beginning were the ones who survived in their

struggle against the unforgiving landscape of the Far North.

Left: "Stories of Life", by Fazil Najafov.

Bronze. Happiness and unity are exposed to the public; misery

and discord are hidden. 1987. Left: "Stories of Life", by Fazil Najafov.

Bronze. Happiness and unity are exposed to the public; misery

and discord are hidden. 1987.

During the long journey

to the camps, some of the prisoners fell ill. The camp administrators

realized that some of the elderly would not be productive laborers,

so they were sent back to the Mainland [Mainland here generally

refers to parts of the USSR other than Siberia and the Russian

Far East where the GULAG camps were located. In the case of the

author Eyyub Baghirov, it often implies Azerbaijan or Nakhchivan].

Some of them were left in the transit camps in Irkutsk [Irkutsk

is the administrative center of Irkutsk Oblast, which is located

in southeastern Siberia] and Vladivostok. Many of them were not

able even to finish their sentences and met their deaths in the

taiga forests of Siberia and the Far East. The well-known Azerbaijani

writer and dramatist - the unforgettable Husein Javid - was one

of them. By that time, he was aged and broken from prison. And

he couldn't see well. He was separated from our journey in Magadan

because of illness and then sent on to the transit camp in Irkutsk.

Our ship launched at night from Vladivostok and started heading

towards Magadan. We left Uncle Ivan, Shirali Akhundov, Khalil

Aghamirov and other comrades in Vladivostok. On the way we faced

a ferocious storm in the Okhotsk Sea [Okhotsk Sea borders the

Russian Far East along the Siberian coastline.

Ships carrying thousands of prisoners to work in the GULAG of

the Kolyma region often would dock at the port in the city of

Magadan. Okhotsk Sea is icebound from November to June, and is

often shrouded in heavy fogs]. The unbearable crowded conditions,

the clamor and banging of the ship's engines, tossing from the

rough waves on the sea frightened us to death.

Eight days later, the ship with its thousands of prisoners arrived

at Nagaev Pier, which was still in a very primitive condition.

They delayed unloading the ship.

Finally, the steel doors of

the prisons were opened and the guards escorted us out. Our chests

felt very tight with apprehension. We assumed that we had been

brought there to die.

We continued our journey on foot, carrying handmade sacks on

our shoulders that were filled with our basic necessities. Eventually,

we arrived at Morchekan [Morchekan: a prison base in Siberia

used for quarantine of newly arrived prisoners and for delousing].

After we were processed through a treatment of showers to get

rid of lice, we entered the transit camp of Magadan. This camp

was located not far from the entrance to Kolyma, which was under

heavy guard.

Since there were already thousands of prisoners there, no shelters

or even tents were available for us and so we had to sleep under

the open sky. As usual in this kind of situation, we huddled

as close to one another as possible, just to keep warm. Such

a great number of people from so many different backgrounds created

so many difficult situations and, in turn, provided great opportunities

for criminals.

We Southerners were very uneasy and frightened about the prospect

of spending the night outdoors, exposed to the northern climate

of Kolyma. That night was so cold; and in the morning, it snowed.

Actually, it was here in this camp that I first began to realize

that when it snows, the weather is warmer than when the sky is

clear. In the morning some of us, including me, were ill with

fever. Some of the prisoners themselves were doctors who administered

first aid from their Red Cross bags.

Kolyma Doctors

Let me comment about the Kolyma doctors. Most of them upheld

the highest moral standards. The prisoners referred to them as

"the Red Cross". These doctors considered it their

primary goal to offer medical assistance to prisoners - often

under unbearable conditions. And their help extended beyond medical

treatment. For example, they often arranged for people to be

assigned to less strenuous work; in other words, to free them

up from hard physical labor. Doctors often recommended more reasonable

work after a hospital treatment. They did many other things as

well, always demonstrating their commitment to the Hippocratic

oath.

These comrades would bring bread, sugar and other necessities

in an effort to keep prisoners alive who were weak with exhaustion

or were already known as "goners"["Goner"

a term used in the prison camps to refer to someone who was beyond

hope of recovery and nearly dead]. To a great extent, the survival

of these prisoners depended upon these medical personnel. They

determined the level of work that a prisoner would be assigned.

They could increase the caloric level of a prisoner's meal. They

could admit a person into the hospital or arrange for someone

who had become disabled to return and visit the Mainland.

Though years have passed, I still remain enormously thankful

for these medical comrades, who through their own bitter fate,

were forced to bear that difficult life with us in Kolyma. Among

them were also some of my fellow countrymen: Professor A. Atayev,

M. Shahsuvarli, M. Mahmudov and others.

In the transit camp in Vladivostok, one of our fellow countrymen

from Baku became ill. It was Gazanfar Garyaghdi who had entertained

us with his robust songs along our journey. He was shaking from

cold and had already started to turn blue.

Our military friends got worried. Despite how freezing the weather

was, they took off their overcoats, put them under sick Gazanfar

and covered him. We took care of him, and little by little, he

began to recover. So often during those critical times, it was

only those deep brotherly ties that saved our lives.

DalstroI

Among the prisoners, there were also those who knew the Far East

very well. One of them - I forgot his last name - was a brilliant

storyteller. He also had a wide range of interests. In our spare

time, which was more than enough those days, he would tell us

stories about the Far North. These fascinating stories saved

our minds. He was a true scientist who knew history and geography

as well as the environmental conditions of Kolyma. He could even

name the first discoverers of the region. His stories, continued

for days when we were stuck in that transit camp, and they became

essential for life in the Far North. Unfortunately, after we

were separated in Kolyma, I never met up with him again.

Left: Propaganda poster encouraging prisoners to reach

their daily quota of work, in this case, cutting timber in Siberia.

Those who did were rewarded with a daily ration of 700-800 grams

of bread, instead of 300 grams Left: Propaganda poster encouraging prisoners to reach

their daily quota of work, in this case, cutting timber in Siberia.

Those who did were rewarded with a daily ration of 700-800 grams

of bread, instead of 300 grams

When we got to know

the situation, we discovered that this wide expanse of territory,

which included Kolyma, Chukotka [Chukotka is the farthest northeast

region in Russia on the shores of the Bering Sea. It was formerly

an autonomous district subsumed with Magadan Oblast. It is known

for its large reserves of oil, natural gas, coal, gold and tungsten

[Wikipedia], Indigirka [A region near the East Siberian Sea.

The river by the same name freezes up in October and stays under

the ice until May or June. The region is known for its gold prospecting

industry [Wikipedia], and even part of Yakutia [The Sakha (Yakutia)

Republic is a federal subject of Russia (a republic) in northeastern

Siberian Russia. Its main economic resources are diamonds, gold

and tin ore mining [Wikipedia], had vast natural resources and

was governed by Dalstroi MVD USSR [Dalstroi refers to the GULAG

administration in the Russian Far East; that is, the extreme

eastern parts of Russia, between Siberia and the Pacific Ocean.

The Russian Far East should not be confused with Siberia. It

does not stretch all the way to the Pacific [Wikipedia]-the head

administration of Far North. This administration itself was a

"government with the government".

Since its establishment in 1931, Dalstroi had widely utilized

the labor of prisoners. The real owners of Kolyma-the prisoners

- had been brought to this land by the shipload. In addition

to the prisoners, many contractors flocked to this place drawn

by the high salaries.

Dalstroi with its vast resources in mining, fishing, and forestry,

was developed by the enormous force of cheap labor and made a

tremendous contribution to Stalin's industrialization of the

country. The entire administration of the Dalstroi - economic,

administrative, physical and political - was in the hands of

one person who was invested with many rights and privileges.

The first head of Dalstroi was Eduard Berzin, a Chekist [The

Cheka was the first of many Soviet secret police organizations,

created by decree on December 20, 1917, by Vladimir Lenin and

led by Felix Dzerzhinsky After early attempts by Western powers

(Britain and France) to intervene against the Bolsheviks in the

Russian Civil War (1917), and after the assassination of Petrograd

Cheka leader Moisei Uritsky followed by Fanya Kaplan's attempt

to assassinate Vladimir Lenin, the Soviet leadership and the

Cheka became convinced that there was a wide ranging conspiracy

of foreign enemies and internal counter-revolutionaries. Therefore,

they poured resources into the intelligence service to combat

this conspiracy. The Cheka quickly succeeded in destroying any

remaining counter revolutionary groups [Wikipedia].

Soviet secret policemen were referred to as Chekists throughout

the Soviet period and the term is still found in use in Russia

today. On February 6, 1922, the Cheka was reincorporated into

Ob'edinennoe Gosudarstvennoe Politicheskoe Upravlenie (OGPU),

State Political Administration, or a section of the NKVD of the

Russian SFSR [Wikipedia]. This was the forerunner of NKVD and

KGB] who was shot later in 1938.

At that time, Magadan was a city known for its cold, dry climate

and strong winds. The buildings were one - and two - stories.

In the late 1930s the virgin taiga started abruptly at the edge

of the city. Today a piece of the taiga remains within the city

as a park.

Three days after our arrival in Magadan, Valentin Aleksandrovich

Tsaregradskiy, who was the head of Main Geological Administration

and Deputy Head of Dalstroi, visited the transit camp to talk

to us. He chose specialists and professionals - first of all,

geologists - to work for the development of the economy of Dalstroi.

We had heard that he was one of the first discoverers of Kolyma.

Somehow Tsaregradskiy was able to gain our trust. He spoke directly

and honestly to us, trying to allay our fears. Although we had

tried our best to anticipate what to expect in the years that

stretched before us; still, there was such a stark contrast between

Baku and the wild taiga of Kolyma, that it put me under tremendous

psychological stress. This feeling never left me.

We were living among people who were physically and mentally

exhausted. They would wake up in the middle of the night, terrified

by nightmares. In those difficult days, the only thing any of

us wanted was a kind word and some humane treatment.

Later on, after being under Tsaregradsky's supervision for a

while, I was convinced that he was a decent human being. He himself

was interested in painting and I heard that in his home, there

were landscape paintings of the Far North that he had painted

himself. He would often walk silently in the taiga, alone, without

any guards. There were times during the geological explorations

that he would sleep in the same tent and eat from the same bowl

as the other workers did. Many Dalstroi workers held him in high

esteem.

Convoy to Butigichag

One gloomy morning at dawn, we were transported in open trucks

from Magadan. Our route took us through some of Kolyma's uninhabited

virgin territory. We drove for a while, leaving behind the fog

- enshrouded Nagaev pier. The weather became colder; though it

was dry. When the convoy stopped, the guards would get out and

take a rest, and we would go in search of some "gift of

nature", such as cedar nuts. It kept us from becoming weak

from hunger.

We were surprised when the guards didn't pay much attention to

us prisoners when we jumped out of the trucks. Obviously, they

already knew that it was impossible for us to escape anywhere.

They had the right to shoot us any time "for attempting

to escape". Where could one escape in the wild wilderness

of the taiga? If you died, the wild animals would devour you.

If you succeeded in managing to reach civilization, you would

be reported and receive an extended sentence that was even harsher.

In reality, it was practically impossible to escape from the

camps of Kolyma, although such attempts were made, especially

in the spring and summer.

The sites for these camps, which were located out in the middle

of uninhabited taiga forests, had been very carefully selected.

They were situated in sheltered areas between boulders and hills.

With the help of a large staff of armed camp security, thousands

of sheepdogs, Chekists, and army frontier guards, it was so easy

to catch anyone trying to escape.

Besides, there was an enormous network of informers among the

prisoners - secret agents appointed by camp administration who

also helped to prevent the prisoners from escaping. En route,

we saw that on the edge of the road near the ditch, some places

already were covered with gravel.

Later on, roads were constructed with prison laborers, who worked

with practically no equipment - only axes, shovels, trucks and

wheelbarrows.

The Kolyma road construction workers had the most difficult job.

The authorities had in mind for Dalstroi to become the first

government trust for the development and road construction in

the North. For this reason, masses of prisoners were brought

to Kolyma to construct roads through the dense taiga forests,

the boulders and swamps, rivers and canyons.

Among the prisoners in Kolyma there were many road workers. At

any time of the year - day or night - one could see thousands

of laborers working along the roads. In winter, they would clear

the roads of snow to make way for the vehicles. It was very difficult

to look at the prisoners, with their numbed faces covered with

frost and snow, clothed only in torn padded cotton jackets. Sometimes

they would use their shovels pound down the snow or just wave

their shovels back and forth to keep moving so they wouldn't

freeze.

The guards would often chase the prisoners with their dogs. They

would make them work for many days continuously - not allowing

them to return to warmth to regain their strength. They often

were given a frozen piece of bread and a jug of tinned food,

which had to be shared between two people.

We headed up into the Kolyma Mountains, traveling such a long

way, passing through forests. There were no inhabitants. We bumped

and swayed from side to side in the truck.

Despite how exhausted we were, the trucks continued moving forward,

day and night. The drivers constantly had to use their brakes.

Actually, despite our own pathetic situation, we felt sorry for

the drivers who had to navigate such dangerous passes through

the mountains and taiga.

During the short breaks, the drivers wouldn't even get out of

the trucks to stretch their legs. They would just fall asleep

right there on the seat.

They were so tired that we would have to wake them up to start

moving again. Especially when we passed close to the rivers where

the road was so icy and slippery, the drivers had to be so alert

and cautious. They would get out of their trucks, search for

the right place to drive in order to avoid any surprises or accidents.

Sometimes the snow would drift across the road, and the trucks

would get stuck. We would get out and push the trucks out of

the snow with our bare hands. But all in all, the drivers in

Kolyma were very courageous and skillful.

There were still deer darting along the roads of Kolyma as no

truck had ever passed through there before. We would see the

local indigenous people using herds of deer to transport the

equipment of the geologists and construction workers.

At dusk our convoy arrived at the main base, which was located

in the foothills of the Podumay. On the way, we discovered that

we were on the way to Butigichag [Butigichag: the name of the

Tenki Administration of Dalstroi where an ore factory was constructed],

the Tenki Administration of Dalstroi. There were constructing

an ore-concentration factory there. The head of construction

was our fellow countryman Museyib Jafar oghlu Akhundov from Baku.

To arrive in Butigichag, one has to navigate the dangerous mountain

Podumay Pass [Podumay Pass: One of the most treacherous passes

in the Kolyma Mountains. Most of the year, it was closed to vehicular

traffic because of the severe climactic conditions] which is

about 15 km long.

Our long truck convoy continued along the taiga road. It was

already dark when we arrived at the main base, in the foothills

of Podumay, but the pass was already closed due to blizzards

and snowdrifts. It was impossible to drive through it. We had

arrived too late. We would continue the rest of the trip on foot

across the treacherous ice and snow.

|

"We were living

among people who were physically and mentally exhausted. They

would wake up in the middle of the night, terrified by nightmares.

In those difficult days, the only thing any of us wanted was

a kind word and some humane treatment."

-Ayyub Baghirov

in "Bitter Days of Kolyma"

|

That night we stayed at the camp and, more importantly, we got

some sleep. We were lucky that the storm had quieted down. The

next day, we started our climb up the Podumay Pass with sunny

weather. We were literally crawling up the mountain, exhausted

and eager to get rid of our heavy clothes. Climbing was so difficult.

To make it easier, we started to rid ourselves of any unnecessary

personal items. On the cliffs of the tortuous winding mountain

road, not only was there fresh snow, but also hardened ice that

still had not melted from previous years.

For the first time here, I gazed out at the amazing panoramic

views of these mountains. It brought back memories of my dear

Caucasus. On these snow-covered peaks, the air is fresher, and

it made us want to become lighter and soar over the mountains,

higher and higher, like a lone eagle.

Finally we reached the final peak of the mountain and before

us lay the taiga valley with its golden hues of autumn. The view

was breathtaking. Rivers snaked through the land, and the sound

of distant rushing waters awakened us from boredom into joy.

It's difficult to describe our feelings at that time. There we

were in such a beautiful corner of the world under escort of

guards and sheepdogs, having been accused of being "Enemies

of the People". It was impossible to bear the irony of such

injustice. Soon we understood that we were "politicals"-a

name given to us by the government. We were treated like actual

enemies of the government-executed, starved, assigned to carry

out their exhausting slave labor. After resting a short while

at the top of the mountain, the guards announced that we would

begin our descent. We started down slowly.

Fortunately, going down was easier than coming up had been. We

were soon at the bottom and felt close to life, warmth and work.

Surviving the Cold

Work? Why do I speak so fondly about labor? It's because, as

I later discovered, without labor in these dense forests, a person

falls apart and starts to go crazy. I recognized that this was

happening especially among those prisoners who were there as

criminals. They didn't want to work. They only wanted "to

get to heaven on the sweat of some one else's brow."

But they soon relented. In such places, a person cannot live

without labor. Work helps you to survive. Obviously, this is

the reason why the organizers of GULAG had wisely located the

camps in the midst of the wildest terrains of the taiga, where

practically no human being had ever set foot before. This is

where they took us as their free slave laborers. Simply, if you

didn't work, you wouldn't survive in the taiga. First of all,

you would die from hunger.

The sun had already set behind the mountains when we arrived

in a virgin forest of tall larch trees. There were three heated

tents that belonged to a group of field geologists. A little

further on in the forest, there were two more official cabins

built of stone. These cabins were probably intended for prisoners

in transit. We were surprised to return to civilization with

cabins, for we had lived in prison cells, prisons on ships, cattle

cars, and tents in transit camps. Now we were accommodated in

cabins where we were able to light a fire and heat some water.

It was the first time we had ever been able to wash with warm

water.

We gathered around to eat something and lie down to sleep. Suddenly

two men entered our cabin, wearing warm clothes that were appropriate

for the North. They greeted us and asked whether any of us were

from the Caucasus.

I admitted that I was, and they came over and greeted me. One

of them - Mammadagha - was from Baku. The second one was from

Tbilisi. His name was Valiko. These young men had arrived in

Kolyma the year before and had overcome the difficulties and