|

Winter 2003 (11.4)

Pages

36-41

Former Soviet Union

Portrait

of the Next Generation

by Dr. Nadia M. Diuk

More than a dozen years

have passed since the collapse of the Soviet Union (1991) and

the emergence of 15 independent states. And yet, the ruling elites

of most of these countries (with the exception of the Baltic

States - Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia - and now, Georgia) are

still firmly rooted in networks of the old Soviet state. The

upcoming, next generation, however, is waiting in the wings and

growing, both in numbers and sophistication. But who are the

members of this next generation? Very little empirical research

has been conducted on post-Soviet youth, especially in Azerbaijan. More than a dozen years

have passed since the collapse of the Soviet Union (1991) and

the emergence of 15 independent states. And yet, the ruling elites

of most of these countries (with the exception of the Baltic

States - Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia - and now, Georgia) are

still firmly rooted in networks of the old Soviet state. The

upcoming, next generation, however, is waiting in the wings and

growing, both in numbers and sophistication. But who are the

members of this next generation? Very little empirical research

has been conducted on post-Soviet youth, especially in Azerbaijan.

This First Free Generation (those born after 1968) already constitutes

a large proportion of the population. The driving force of this

age group would have been 18 years old when Gorbachev announced

the policy of Glasnost and Perestroika. Across that vast expanse

of land whether they were in school in Kaliningrad [a Russian

enclave located near Poland], Kyiv [Ukraine], Baku [Azerbaijan],

Tashkent [Uzbekistan] or Vladivostok [Russia in the Far East],

they were all educated under the Soviet system and taught according

to the same curriculum, every day of the week. Throughout their

school years, they were assured that regardless of whether they

pursued a technical or an academic career, a secure job was awaiting

them until they retired.

But just as this age group was finishing high school in 1986

and moving on to further education, the political situation began

to change, and the guarantee of a secure future "from cradle

to grave" came into question. By 1991, the notion of a destined

future disappeared, together with the monopoly of the Communist

Party.

These young people were left to fend for themselves. Their younger

brothers and sisters have less memory of the "bright future"

that was promised under Communism. Those born in 1986, who virtually

have no memory of the Soviet past, will become first-time voters

in the municipal elections of 2004.

Who are the members of the next generation? How do they think?

What are their aspirations? Will they strive for justice, freedom

and equality? How do they spend their leisure time? How much

do they trust the government and its institutions? What effect

has independent statehood had on the youth in the various republics,

and how far have they diverged from each other? How much has

the past influenced their values and expectations?

Below: The Soviet Union stretched

across 11 time zones. Map emphasizes the three countries that

were selected for this survey-Russia (yellow), Ukraine (purple),

and Azerbaijan (red).

To address these questions and to compile a comparative portrait

of the Next Generation in three leading post-Soviet states -

Azerbaijan, Russia and Ukraine, a poll was conducted in each

country using a questionnaire that was almost identical.1 The

poll was conducted nationwide among the same age group. Such

polling takes place fairly frequently in Russia; to a lesser

extent, in Ukraine; but hardly at all in Azerbaijan. This article

will therefore focus on data about Azerbaijani youth and the

unique trends revealed among the younger generation, with occasional

references to Russia and Ukraine.

Now that Azerbaijan has joined the capitalist world along with

the other post-Soviet republics, salary and income has become

the determining factor for many issues, including access to goods,

education and ultimately social status. Previously, all of these

economic issues were determined by the Communist Party. Analysts

who look at the level of democratization in a country often focus

on the development of the middle class because people in that

level of income have an interest in defending their financial

gains and are, thus, interested in politics.

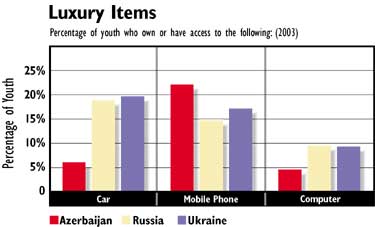

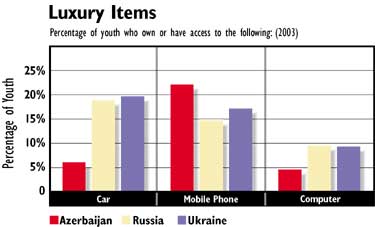

Left: A

recent survey conducted as part of Nadia Diuk's project "The

Next Generation of Leaders in Key Post-Soviet States,

compared youth

in three countries of the former Soviet Union-Azerbaijan, Ukraine

and Russia. Left: A

recent survey conducted as part of Nadia Diuk's project "The

Next Generation of Leaders in Key Post-Soviet States,

compared youth

in three countries of the former Soviet Union-Azerbaijan, Ukraine

and Russia.

The survey attempted to construct a profile of the Next Generation-youth

born after1968-as very little is known about this group, especially

in the West. Note here that youth in Azerbaijan had the greatest

access to mobile phone. Of those polled throughout Azerbaijani,

22 percent said they had a mobile phone, while 50 percent had

them in Baku.

Sociologists

in Russia have estimated that the income that determines middle

class status in Russia is around $300 to $500 per month. Approximately

5 percent of young Russians fall into this category, as do 1.3

percent of young Ukrainians. In Azerbaijan, only 0.4 percent

earned this level of salary.

Income levels for young people in Azerbaijan indicated that the

majority had an income of $20 or less per month - 47.4 percent.

This included 57.8 percent of the 18 - to 24-year olds, who would

not be expected to be bringing in much income. The largest percentage

of young people - 19.4 percent - had an income of less than $10

per month, with 15.2 percent claiming no income at all.

However, walking around Baku, one can't help but notice many

affluent young people. Statistics show that youth in Baku earn

far more than those in the regions. Whereas an income of more

than $50 per month outside of Baku is relatively rare among young

people, the average income per month for young people in Baku,

who responded with an actual figure, indicated that they earned

$50.

Earning more than

Parents

Anecdotal evidence also suggests that many of the younger generation

are accommodating themselves more easily with the new economic

conditions, and are often financially better off than their parents.

This phenomenon is relatively new for countries where, under

the Soviet system, parents were generally better off than their

children, and the family budget was planned around this certitude.

In this poll, the question was posed: "Is your monthly income

more, or less, than that of your parents?" In the sub-group

(30 - to 34-year olds), 29 percent earned more, and the overall

figure was 17.8 percent. Although this figure is not high, nonetheless,

it is likely that this is the first time in generations that

a considerable number of young people are earning more money

than their parents. The psychological effects of this reversal

may have repercussions in social attitudes and political behavior

in the future.

The best way to assess income across three countries is to look

at purchasing power since currency and also the social support

infrastructure is different. Russia's youth led Ukrainians and

Azerbaijanis in being able to comfortably afford more day-to-day

items. In Azerbaijan, the largest number - 47.2 percent - indicated

that they had "enough for food, but not for clothing".

Marriage

Statistics on marriage and children revealed some surprises.

In Azerbaijan, which is considered to be a conservative country,

there were many youth who were not married. The sample indicated

that 52.8 percent of the respondents were not married and had

never been married. This is rather remarkable for a country,

which is generally described as traditional. Although 3.2 percent

said that they were divorced, only 0.4 percent claimed to be

"living together" in an unregistered relationship (as

opposed to 6.1 percent in Russia). As far as children were concerned,

59.2 percent claimed to have had none (58.3 percent in Russia,

and 49.1 percent in Ukraine).

Post-Soviet concerns about low birth-rates have arisen from time

to time and were considered a particular problem in the

Baltic States in the early 1990s, when the birthrate dropped

to around one child per set of parents.

Living at Home

In response to the question: "Do you live with your parents?"

in Azerbaijan, 72 percent answered "yes". In Ukraine,

the figure was 61.7 percent; and in Russia, 58.5 percent. Young

Azerbaijanis also lived together with more people under the same

roof: on average, 4.7 people (3.6 in Russia, and 3.7 in Ukraine).

Mobile Phones

Despite low levels of income, many young people in Azerbaijan

had gained access to the symbols of modern life - automobiles,

mobile phones and the Internet. Young Azerbaijanis were not very

mobile: only 6.2 percent had access to an automobile. But Azerbaijani

youth fared better when it came to modern technology. Throughout

the country, 22.2 percent used a mobile phone, (12.9 percent

of Russians, and 14.8 percent of Ukrainians). Statistics for

Baku indicated that 50 percent of the young people polled used

a mobile phone.

Internet

Usage of Internet reveals very interesting statistics. In Azerbaijan,

while only 4.3 percent claimed to have access to a personal computer,

13.4 percent of young people used the Internet, and this figure

increased to 21.4 percent among the youngest group of 18 - to

24-year olds. Also, it is significant to note that in Baku, 37.9

percent of the young people that were polled used the Internet.

Government as "Big

Daddy"

This survey attempted to gauge how far the youth of today have

moved away from assumptions that were inculcated into their parents

during their Soviet education. The standard Soviet view was that

the State should take care of the individual "from cradle

to grave", and that each citizen should have confidence

in the wisdom of the State and its institutions, even though

in practice, the level of state - provided services was rarely

satisfactory.

When asked about the level of intervention by the State into

the economy of the country, young Azerbaijanis demonstrated fairly

liberal thinking: 8.8 percent supported the idea of a completely

free market economy with no government intervention (5 percent

in Russia; 11.6 percent in Ukraine). But when the question was

posed in a more specific way: "What should be the relationship

between the government and its people?" Young Azerbaijanis

showed themselves to be more paternalistically oriented than

their post-Soviet colleagues: 68.2 percent opted for the response:

"Government should care for all of its people" (Russians

polled 64.3 percent; Ukrainians, 62.6 percent).

What explains this strongly paternalistic orientation a decade

after the demise of the command administrative system? Unlike

the Soviet government, the governments of the new independent

States do not claim to look after their citizens. Is this belief

simply part of the legacy which has been passed down from older

generations?

Trust in Close

Relationships

A series of questions was posed to gauge the level of trust in

social and political institutions. Questions probed the attitudes

held about different types of institutions: (1) the level of

trust and confidence in friends and family; (2) institutions

with a "social service" purpose such as insurance companies,

banks, medical practitioners, and educational establishments;

(3) institutions of civil society such as the media, religious

institutions, trade unions, non-governmental organizations; (4)

institutions exerting power, such as the army and the military;

(5) institutions involving the justice system; and (6) political

institutions and organs of executive power, such as the parliament,

the President, the President's administration, and political

parties.

The striking feature was that, apart from the overall high level

of trust in friends and family, the youth of all three countries

generally did not trust state institutions or institutions of

civil society. In Azerbaijan, the most active distrust was against

the police (64.4 percent) and the parliament (64.4 percent) with

insurance companies (60.8 percent) and banks (55.4 percent) not

far behind. The courts received a "distrust" rating

of 52.6 percent and political parties - 50.8 percent.

Even though young Russians and Ukrainians distrusted their political

parties even more, this is still a figure that should cause some

concern for Azerbaijan's future: the key institutions of a democratic

state had so little support.

Another institution that is important for the development of

civil society is non-governmental organizations. Here again,

young Azerbaijanis showed a higher level of trust than did Russians

and Ukrainians, but the figures were, nonetheless, ambivalent

with 40.6 percent, expressing complete and partial trust, and

43.2 percent indicating complete and partial lack of trust. In

Azerbaijan, young people showed the most confidence in their

relatives (87.6 percent) and friends (87.2 percent).

Perception of Military

Surprisingly, the next most trusted institution was the army:

77.6 percent of young Azerbaijanis expressed partial or complete

trust in the army. This is a figure that, by far, surpasses the

statistics found in Russia (51.9 percent) and Ukraine (47.8 percent).

In a survey such as this, it is not possible to ask the reasons

why a certain response is chosen, although attitudes toward the

army and service may be assumed to reflect the level of patriotism

among youth, regardless of whether they themselves are ready

to fight for their country or not. The support for the army among

young Azerbaijanis also was evident in another set of questions.

A relatively high 65 percent of young Azerbaijanis chose the

first response: "Every real man should serve in the army"

when presented with a range of responses that also included:

"Military service is an obligation that should be repaid

to the State even if it does not suit your interests", and

"Military service is senseless and dangerous and should

be avoided at all costs".

The younger age group registered 61.7 percent in favor of "real

men". Among young women, 70 percent also opted for that

choice. Very few young Azerbaijanis (6.4 percent overall) considered

military service as "pointless and dangerous; people should

avoid it at any cost". In comparison, 50.9 percent of young

Ukrainians believed that "a real man should serve in the

army"; while in Russia the figure was relatively low at

38.7 percent.

The difference seen in Azerbaijan may be due to several factors.

Many young people still remember military action themselves or

seeing their older brothers fight in the war in Karabakh [against

Armenians]. The Azerbaijani military also has more prestige,

especially the Officer Corps, which has developed connections

with Turkey, where the military tradition is a pillar of the

secular Muslim society.

The next highest rating of trust was for the mass media, which

was "partially or completely trusted" by 72 percent

of young Azerbaijanis. This is a surprising statistic for those

who follow the democratic development in Azerbaijan, considering

that the TV and radio are heavily monitored by the government.

The print media, whether controlled by the government or the

opposition, is also a long way from being independent and objective.

Political Parties

How did the first post-Soviet generation relate to and participate

in politics? Even though the years since 1991 have not brought

a full liberal democratic system to Azerbaijan, this is still

the first generation that has had the opportunity to experience

real politics. But how interested are young people in politics,

and what do they understand by that term?

In Azerbaijan, 39.8 percent did not indicate a political party

preference, although 9.8 percent were interested in political

parties with an ecological inclination; social democracy attracted

5.2 percent, and 14.8 percent opted for a national-democratic

preference. A surprising 9.8 percent expressed support for a

communist ideology, and 4.4 percent for a political inclination

that was "religious".

Another poll conducted by the Adam Center in November 2002 named

specific political parties and came up with the following results:

31 percent of the young people claimed that none of the parties

was close to their point of view, but the top two vote-getters

were the opposition Musavat Party with 23 percent, and the pro-government

Yeni Azerbaijan party with 15 percent. According to the age-group

break down, however, it appeared that the older youth in Azerbaijan,

were more inclined to identify with the opposition Musavat Party,

which had a 27 percent rating in the 30 - to 34-year old group,

and 21 percent among the youngest 18 - to 24- year-olds. Pro-government

Yeni Azerbaijan was supported by 18 percent of the youngest groups

and by only 12 percent of the oldest.

Which Freedoms?

More than a decade after communism, what are the values and beliefs

that lie at the heart of the next generation's view of the world?

Young people were asked to choose which values they considered

most important out of the following list: (1) freedom of speech,

(2) freedom of movement, (3) freedom of conscience, (4) the right

to a defense against unlawful arrest, (5) the right to work,

(6) the right to a home, and (7) the right to education.

Azerbaijanis differed from their Russian and Ukrainian counterparts

on these questions. The top four choices made by Russian and

Ukrainian youth were the same: (1) the right to work, (2) the

right to a home, (3) the right to education, and (4) freedom

of speech. In Azerbaijan, the list was (1) the right to work,

(2) freedom of speech, (3) the right to a home, and (4) right

to an education.

Another question was posed to measure how far the youth have

moved from the Soviet ideal that valued equality over freedom.

They were asked to make a choice between two formulations of

the question: "Freedom and equality are both important,

but if it were necessary to choose between them": (1) "I

choose freedom as the more important because people should live

as they choose without limitation", or (2) "I choose

equality as the more important because social differences between

people should not be too great and nobody should be able to take

advantage of undeserved privileges."

In Azerbaijan, 53.8 percent opted for equality, while 43.4 percent

chose freedom. As expected, men chose freedom more often (47.4

percent) than women (39.6 percent). Differences in Azerbaijan

also depended upon age and level of education: the 18 - to 24-year

old group broke down evenly at 48.1 percent between freedom and

equality, while the older youth more often chose equality. Those

with higher education were also more likely to choose freedom

- 62.2 percent.

Regional distributions in Azerbaijan were revealing: Shirvan

expressed the most interest in freedom - 75 percent. Ganja indicated

only 20 percent support. Surprisingly, the figures in Baku were

47.1 percent for freedom and 52.3 percent for equality.

International Affairs

In the past 10 years, there has been a complete turnaround in

official attitudes toward foreign countries in the post-Soviet

region. Countries that were considered "the Enemy"

during the Cold War, have become "strategic partners"

during the 1990s and, in some cases, even close allies after

September 11, 2001 [the date when terrorists attacked New York

Trade Center and Washington's Pentagon].

With NATO and the European Union on their borders, and as members

of the Council of Europe, these three countries - Russia, Ukraine

and Azerbaijan - are now all well on their way to becoming integrated

into the international community. Private attitudes toward the

outside world and especially toward the West were different,

however. Young Soviet citizens in the 1960s and 1970s, treasured

their bootleg cassette tapes of the Beatles and sought denim

jeans on the black market, convinced that their government was

presenting a false picture of the West. But now that young people

are free to travel as finances will permit, what does this generation

think about the outside world?

The survey included questions on how young people viewed the

international environment with regard to their own country, as

well as pragmatic assessments of where they themselves would

choose to travel to live and work for a while, or even to emigrate.

Favored Countries

Young people were asked which geopolitical alignment would be

best for their country. Most young people in Azerbaijan - 29.4

percent - considered Turkey to be the best partner for their

country's future development, narrowly surpassing Russia for

first place - 28 percent. Europe trailed in third place - 21.6

percent. The United States was rated first place by only 15.6

percent of young Azerbaijanis.

Young Azerbaijanis were more eager to leave their country and

also more likely to emigrate permanently than Russians and Ukrainians.

When asked for how long they would like to leave Azerbaijan,

15.8 percent responded "forever". This suggests that

these young Azerbaijanis see better prospects for themselves

elsewhere, with no confidence that the situation will improve

for them. This was borne out by the response to the question:

"Why would you like to leave your country?" "Work"

was cited by 22 percent; 18.6 percent said "to see different

countries", and 4.8 percent would pursue studies. These

figures contrasted with young Russians, who now appear most comfortable

in their own country. Only 4.4 percent of young Russians wanted

to emigrate "forever" and when asked why, the most

frequently cited reason was "to see different countries"-25.8

percent.

These figures corroborated other statistics in the survey, which

show young Russians as having achieved a higher level of income

than their Ukrainian and Azerbaijani counterparts. When asked

their occupation, 27.2 percent of young Azerbaijanis claimed

to be "unemployed, temporarily without a job, or not working"

as opposed to 7.2 percent of the Russians and 16 percent of the

Ukrainians.

In Azerbaijan, the top choice for personal travel was Russia,

followed by Germany. Turkey and the US nearly tied in fourth

place. These selections appear to reflect the more realistic

possibility of young Azerbaijanis traveling to Russia for work.

Language Choice

The 30-year olds of Russia, Ukraine and Azerbaijan still remember

an educational system where the curriculum for all three republics

was almost identical on any day of the school week, and where,

despite the existence of national languages, everyone needed

to know Russian in order to progress in their career. For the

20-year olds, educated in independent states, the use of Russian

has not been so clear-cut. Although it is no longer the state

language in either Ukraine or Azerbaijan, all those years of

Soviet language policy have left a persistent use of the Russian

language and a complex set of psychological attitudes.

In Azerbaijan there has been a strong countervailing policy with

the introduction of the Latin alphabet and the use of the Azeri

language. The surveys conducted in Ukraine and Azerbaijan started

with a set of questions on language preferences. In Azerbaijan,

89 percent considered themselves Azerbaijani, with 6.6 percent

Russians and 2.8 percent Lezgians. However, when presented with

a choice of which questionnaire to fill out - Russian or Azerbaijani

- 23.6 percent preferred Russian, even though only 11.6 percent

claimed Russian as their native language.

The survey posed a broad range of choices on language. In Azerbaijan,

33.9 percent claimed knowledge of Russian "as a foreign

language". Inside the home, 74.2 percent claimed to use

Azeri exclusively. With friends, 23.2 percent of young Azerbaijanis

used both Russian and Azeri, and 17 percent used both in the

workplace. Among friends, 69.4 percent of Azerbaijani youth used

just Azeri.

Ethnic Tolerance

The survey attempted to determine attitudes towards different

nationalities. After decades of trying to cultivate the notion

of Soviets as the same nation, it might be expected that these

youth would hold tolerant attitudes toward one another. The data

showed significant differences. Each nationality was asked to

specify how it views the other two: (1) "with sympathy and

interest", (2) "calmly, without any particular feelings",

(3) "with irritation and hostility," or (4) "with

mistrust and fear".

Young Azerbaijanis viewed Russians and Ukrainians as rather benign

and friendly. But the level of tolerance by Russians and Ukrainians

towards Azerbaijanis was much lower. Among young Ukrainians,

71.9 percent viewed Azerbaijanis with interest or without particular

feelings, while 11 percent had a hostile attitude and 10.2 percent

viewed them with fear.

Young Russians had an even less favorable view of Azerbaijanis:

50.2 percent viewed them without particular emotions (among those,

only 2.6 percent indicated any sympathy and interest), 28.1 percent

viewed them with hostility, and 17.3 percent with fear.

The differences in these figures as they relate to young Russians

may be partly explained by the active negative propaganda that

has been carried out in Russia regarding people of Caucasian

origin in general. The campaign in Moscow against traders (low-class

people selling fruit and flowers in Russia's markets) from the

Caucasus creates an unfavorable image for all citizens of this

region. The relentless negative press about Chechnya and the

other republics located in Russia in the North Caucasus (Daghestan,

Ingushetia, North Ossetia and Kabardino-Balkaria) influences

Russian youth against citizens of Azerbaijan. The responses from

young Russians was not unusual. Such expressions of xenophobia

tended to occur mainly among those with a lower level of education

and those who were unemployed, serving in the army, or, interestingly,

among entrepreneurs.

These findings bear out the general perception that Azerbaijanis

are a very tolerant nation. This tolerance is reflected in the

rather low level of violence in the political culture (especially,

when compared with the seemingly routine assassinations of journalists

and politicians in Ukraine and Russia). Conversely, the rising

xenophobia and intolerance towards foreigners, especially in

Russia, is a trend that has been identified with some alarm by

Russia's leading sociologists. The most recent Parliamentary

election results in Russia, which showed rising support for Vladimir

Zhirinovsky and the newly formed nationalistic "Motherland"

Party, also demonstrated this as a worrying trend.

Religion

The comparative data on religion also shows some interesting

differences between Azerbaijan and the other two countries: When

asked about which faith they belonged to, 89.2 percent of young

Azerbaijanis claimed Islam (6.8 percent Orthodoxy) with only

2.6 percent non-believers ["imansiz"]. Non-believers

in Ukraine constituted 18.9 percent of the youth, and 25.5 percent

in Russia. However, the frequency with which Azerbaijanis visited

their place of worship was about the same as in the other countries.

1.6 percent every week, 6.4 percent once a month, and 31.2 percent

once a year.

The question was also posed: "Would you like your country

to be ruled by Sharia law [Islamic religious law]?" Among

Azerbaijanis, 86.6 percent said "no", and 8.8 percent

said "yes".

Significance of

the Poll

Many of the statistics from this survey could have been predicted.

Some came as a surprise. The high number of unmarried youth should

be of some concern for the future, as well as the high number

of unemployed. The relatively large number of young people ready

to leave their country should also cause policy makers to pay

attention to this generation's needs. Statistics also show something

that is obvious through casual observation, that there is a marked

discrepancy between Baku and the rest of the country on many

issues.

In terms of how the young people of Azerbaijan compare with the

youth of other post-Soviet countries, the survey indicates that

all of them are still under the influence of some Soviet-style

assumptions of their parents' generation. But, in general, even

though the youth of Azerbaijan are less well off financially

than their Russian counterparts, their responses were not so

very different from those of their post-Soviet neighbors.

Dr. Nadia Diuk

is Director for Europe and Eurasia at the National Endowment

for Democracy in Washington, D.C. This article is based on research

for a study, "The Next Generation of Leaders in Key Post-Soviet

States", soon to be published as a book. Contact Nadia Diuk:

Nadia@NED.org.

Back to Index AI 11.4 (Winter

2003)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|