|

Summer 1998 (6.2) Stepping Back

in Time by Susan Cornnell

Imagine being invited to dinner in Ashgabat, the capital of Turkmenistan. Geographically, it's just on the opposite side of the Caspian Sea from Azerbaijan, a bit inland and bordering Iran. However, an enormous cultural distance separates it from Baku. Once, not so long ago, while traveling in Turkmenistan, I was invited to someone's house for dinner. Having lived in Azerbaijan for several years, I prided myself in thinking that I had grown to be quite culturally sensitive.

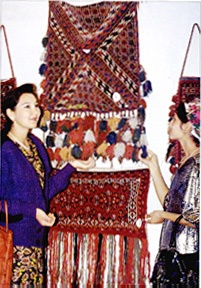

These five Central Asian republics-Turk-menistan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrghyzstan-occupy 1.5 million square miles, stretching from the Caspian Sea to China and extending more the half the width of the United States. Except for the Tajiks, whose language is related to Persian, Central Asians speak Turkic languages, although similarity to the Azeri language didn't seem to be very close, at least, not to our ears. Photo: Hand woven crafts exhibited by young women in Turkmenistan. Ashgabat (Turkmenistan) The main charm of Ashgabat is its people. Located 17 miles from the mountainous Iranian border, the city itself is flat with little color or greenery. We found its architecture uninspiring. The people, however, are delightfully colorful. The majority of women wear the traditional Turkmen "sharavari"-bright, flowing silk which is either brocaded or embroidered-designed as flowing caftans with wide-legged pants. This attire is essential for the hot desert summers with temperatures that can exceed 110 degrees Fahrenheit. Traditional Turkmen usually don't own much furniture, preferring open rooms covered with rich-colored carpets of geometric designs and overstuffed pillows. Their bedding is made of simple padded mattresses, much like Japanese futons, which are neatly folded and stacked in the corner during the day and spread out on the floor at night. Family activities generally gravitate to the floor-eating, sleeping, entertaining. Even the TV, which every family seems to own, is placed on the floor, and the family props themselves up against pillows to watch. My friends and I traveled this ancient Silk Route the Bohemian way-via local buses and trains-which is a story in itself. The police often questioned us at train stations. I have so many memories of the endless pushing and shoving in lines for tickets, riding overcrowded buses and trains along with live animals and baskets of produce. It wasn't much fun getting sick in the middle of the night on a bus traveling through the desert or trying to sleep three to a bunk on an overnighter in Uzbekistan between Samarkand and Bukhara. On the 18-hour train ride between Almaty (Kazakhstan) to Tashkent (Uzbekistan), we once met a former Soviet cosmonaut. The stories are endless. And unforgettable. Samarkand (Uzbekistan) Today, Registan Square is a marvel of domes, archways, gateways and minarets of three ancient "madrasa" (schools of religious instruction) from the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries. It was Lenin who issued a decree to restore the great treasures of art and ancient culture there. The exotic bright blue terra-cotta and majolica glazed tiles in mosaic patterns are remarkable for their brilliance. Originally, they were crafted by Persian, Uzbek and Azeri artisans. The Bibi Khanum Mosque (built 1399-1404) is surrounded with tales of illicit affairs just like the Maiden's Tower in Baku. As the legend goes, the beloved Chinese wife of Tamerlane (Timur the Lame) was constructing this building to honor and surprise her husband, who was away on a distant campaign. The architect, so smitten with her great beauty, refused to finish the work without a kiss from Bibi Khanum. For the price of that simple request (which left unmistakable evidence), the architect was put to death upon Tamerlane's untimely return, and all women were ordered to wear veils. In Uzbekistan, just as in Azerbaijan, tea is the drink of hospitality. It's part of the culture. Uzbekis don't drink black tea as Azerbaijanis do. Theirs is an herbal green tea. Nor is it served in the traditional pear-shaped "armud," but rather in a "piala," a Japanese-style tea bowl which is filled only halfway to show respect for guests. Sugar is not served with Uzbek tea, but bread is. They call it by the same name as Persians do, "nan." The chai-khana (teahouse) is a gathering place for men, just as it traditionally is in Azerbaijan, but here the tea drinkers recline on flat wooden beds covered with a thin mattress of colorful fabric. A plastic tablecloth is spread in the middle; tea and mountains of Uzbek plov (rice pilaf) are served. This traditional dish is served with meats, fruits and chestnuts and topped with chopped greens and tomatoes. Bukhara (Uzbekistan) We met an old "baba"(grandfather) who was picking grapes from his vine. He invited us into his home where one of his eight sons was preparing "nan," the Uzbek equivalent of the flat Azeri "chorek" bread. Nan is baked in a dome-shaped clay oven that is about waist-high and has gas jets on the bottom. The bread dough is round and scored with a design, then placed on a kind of canvas "pillow." The baker thrusts his arm into the oven, making the dough stick to the wall above the flames. When the bread is ready, he pulls it off the oven wall using a stick with a hook on one end. Again, the ever-present "chai-khana" was a source of great refreshment for us, and we chose an establishment in front of the Nadir Divanbeghi Madrasa (completed in 1622) right next to the statue of Nar-ad-din (in Azeri, Molla Nasraddin, the great satirical storyteller of the Middle East). We feasted on plov and dolmas (in this case, stuffed peppers), all foods that reminded us of Baku. Most of the men in Uzbekistan wear a "tubetyeka," a small square or round brightly embroidered cap. We also noticed these being worn in Lankaran, the tea-growing region of southern Azerbaijan, though they were predominately white or black and less elaborately adorned. Uzbekis like to play dominos. Azeri men prefer "nards" (backgammon). We played dominoes with some of the old men at the "chai-khana" in Bukhara. When we won, they took off their "tubeteyekas" and smacked their bald little heads! Perhaps, that's a gesture of amazement! It probably was the first and only time that a foreign woman had beat them at their own game. Kyrghyzstan Kyrghyzstan is about the size of South Dakota and has a small Western community comparable to Baku's. In fact, the whole population of Kyrghystan equals that of Baku's, about 3 million people. Most speak Russian rather than their native tongue. As in Azerbaijan, this tendency is changing as people rediscover their national identity, culture and customs. Bishkek, the capital, is especially remarkable for its natural beauty. An abundance of parks and rows of trees make it seem as gentle and neat as an orchard. The city is situated at an altitude of 2,400 feet and is surrounded by the Alta-Too and Tien Shan mountain ranges which peak at 20,000 feet (nearly four miles high). Bishkek is sometimes called the "roof of the world," as this is where the former USSR, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India and China converge. The city has severe winters and hot summers. Bukharis say, "Why travel, when our land is like Siberia in winter, and Egypt in summer?" The mountains with their permanent snows are simply breathtaking especially when the early, rose-colored dawn gives way to golden afternoons and "drop-dead" sunsets. The air is clean and fresh, and unlike Baku's, it actually smells sweet. Like Baku, the architecture is varied, from the unique, individual homes and small apartment buildings in the center to the vast concrete walls of Soviet-style apartment blocks in the outskirts. There are wide boulevards and parade areas adjacent to large assembly halls which were used for political rallies in former times. There is a rich and thriving national culture of music and literature. A four-hour bus ride (or two hours by car) brings you to thoroughly modern civilization-the capital of Kazakhstan, Almaty. This city is also surrounded on three sides by mountains. Banks, skyscrapers, deluxe hotels, magnificent villas and private complexes of single family homes are scattered along the terraced mountains. Ski resorts and sports centers are extremely popular. Medeo, which is 12 miles outside the capital, has the largest speed skating rink in the world. The people of Almaty are very proud of it, and everyone goes there on Sunday afternoons to skate. More than 100 ice skating records have been set at Medeo; even U.S. Olympic skater Eric Heiden clocked his fastest time there. Almaty is the most Asian of the Central Asian cities. Aside from the public bath (Palace of Baths, which was spectacular), I found few similarities to the eastern way of life back in Baku. They say a great journey begins with one small step. For me, that first step was taken when I got on the plane in the States to go to Baku in 1992. Since then, my eyes have been opened to cultures and customs I'd never dreamed of-the sanctity of tea and bread, the honor of genuine hospitality, national dress, music, even baby bundling. Just beyond the borders of Baku, beyond the sea, the desert and into the Kazakh steppe, there are so many people to meet. From the experiences I've had, I've reached the conclusion that we may be worlds apart in experiences, but in those rare moments of time when we come face-to-face, a common bond is formed. It's a bond that transcends time and place and knits hearts together because of a genuine desire to reach out, to share our lives. For those who have never traveled and visited these parts of the world, I think it's fair to say that the people of Azerbaijan as well as those of Central Asia are potential friends, just waiting to be met. Susan Cornnell is a regular

columnist who has written for us since 1993. |