|

Autumn 2004 (12.3)

Pages

32-37

Baku's Old City

Preserving Our Past

by Mir Teymur

No doubt, there are

many times that Mir Teymur feels like he's "a voice, crying

in the wilderness"-a prophet of doom and gloom, who is not

fully appreciated by those who could benefit most by heeding

his dire warnings. No doubt, there are

many times that Mir Teymur feels like he's "a voice, crying

in the wilderness"-a prophet of doom and gloom, who is not

fully appreciated by those who could benefit most by heeding

his dire warnings.

Mir Teymur is a socially conscious artist and long-time resident

of Baku's "Ichari Shahar" ("Inner City",

or what the foreigners call "Old City"). He claims

that his ancestors have lived there for the past 800 years. As

a result, he lives and breathes this old sector of the city.

Most of his graphics and ceramics relate directly to Ichari Shahar.

Like so many of his contemporaries, Mir Teymur credits his grandmother

for the passion he feels about the Old City. Nargiz Hajinsky

would have been in her early 20s when Baku fell to the Bolsheviks

and her parents' wealth and property, including oil wells, were

confiscated. It was this woman who sensed the tremendous changes

that were occurring in the political structure of the nation.

It was she who suffered tremendous pain of losing so many of

her family members during Stalin's purges of 1937 when they were

executed. And so, today, it should come as no surprise that her

grandson Mir Teymur is the driving force behind the effort to

preserve Ichari Shahar historically.

Left: Baku's most distinguished landmark,

Maiden Tower (Giz Galasi) believed by most to have been built

as a fortress and relay signaling system in the 12th century. Left: Baku's most distinguished landmark,

Maiden Tower (Giz Galasi) believed by most to have been built

as a fortress and relay signaling system in the 12th century.

There are so many things that are so dear to me about the Ichari

Shahar. I feel so connected to it. My family traces its roots

back to the 12th century when Baku was chosen as the residence

of the Shirvan Shahs. That makes us one of the oldest families

living here.

Sometimes I feel like I've studied every stone, every wall, every

building in this place. It makes me stand in awe of what our

forefathers knew and understood about town planning, both in

their attempts to guarantee the security for the community, and

in compensating for the harsh climactic conditions such as Baku's

ferocious winds and the sweltering summer heat.

Take the issue of security, for example. It seems that other

countries and other people have always cast a jealous eye towards

Baku, not only for our oil, but also for other natural resources

such as salt, silk and saffron. So we've always had to deal with

issues of security.

Baku is one of the very few cities in the world, which used to

be surrounded by three walls. Today, only one wall stands; the

outer two have been destroyed and the stone has been used in

the construction of homes. If you study the citadel wall carefully,

you'll see that they were designed to provide multi-layers of

defense. If the enemy succeeded in penetrating the outer walls,

which were not as tall as the final wall surrounding the city,

then the residents could shoot down at them from the round-shaped

lookout posts. If you look carefully, you'll see that in certain

segments of the wall there are holes where hot oil could be poured

down upon the enemy, burning and trapping them so that they would

be unable to escape back over the outer walls.

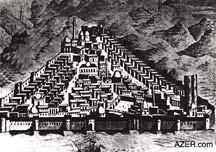

Left: Graphics: The Old City surrounded by

a citadel wall as fortress by artist Mir Teymur. Left: Graphics: The Old City surrounded by

a citadel wall as fortress by artist Mir Teymur.

If the enemy still succeeded in penetrating inside Ichari Shahar,

even the street plan was designed for defense. The streets seem

sufficiently wide enough for four horses to run abreast. But

rather quickly, they narrow so that the enemy would have to reduce

his speed and then the horses would have to follow behind each

other in single file. For the residents, this made it easier

for them to attack the intruder from the roofs of their homes.

And then there were the twists and turns in the lanes. Sometimes,

the streets ran clockwise; sometimes, counter-clockwise. Sometimes,

they led to dead-ends. It doesn't take long for people not accustomed

to Ichari Shahar to lose their bearings and become totally confused

and disoriented. But all these streets and alleyways were laid

out according to plan, not by mere chance and all these characteristics

contributed to the security of the community.

Even hostile climactic conditions were taken into consideration.

Baku experiences ferocious northern winds, but since the houses

were not laid out in straight grids, the intensity of the winds

can be somewhat dissipated.

The residents of Ichari Shahar also learned to compensate for

the sweltering summer heat by building houses with thick walls,

one-meter wide, which served as a cooling system. Even the shade

cast from buildings on either side of the narrow alleyways provided

relief from the direct rays of the sun.

The architecture was planned as an integrated whole which consciously

worked to benefit the entire community. But that's not the way

things work these days. The Ichari Shahar that we once knew is

disappearing right before our eyes. Already, irreparable damage

has been carried out that is likely never to be undone.

I write articles. I make speeches. I'm even in the process of

writing a book about the history of Ichari Shahar. I've been

fighting like this for the last 30 years. Sometimes I feel like

a lone prophet crying in the wilderness, because no one is heeding

my message: "Stop the destruction of our Inner City. Stop

the barbaric destruction of our history. This place embodies

the sacred core of our civilization. Let's preserve it for future

generations."

Illegal construction, the likes of which we are seeing these

days, did not take place during the Soviet period. At that time,

had I made a speech in the morning about the destruction that

is going on in Ichari Shahar, by evening the Secretary of the

District Committee would have been on the scene to investigate.

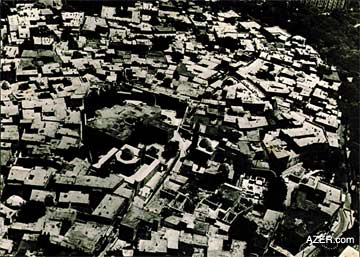

Left: Aerial view of Ichari Shahar: Soviet

Period Left: Aerial view of Ichari Shahar: Soviet

Period

It used to be that people were afraid to destroy any of the buildings

here in Ichari Shahar. During the Soviet period, officials feared

for their jobs if they granted someone permission to demolish

a building. It was easy to bring accusations in the newspapers

against someone for such an offense. So out of fear, Ichari Shahar

retained much of its medieval character.

Of course, it would have been better if people had acted out

of conscience, rather than fear, but these days, they act neither

out of fear nor conscience. Any building can be sold. In addition,

many people who live in Ichari Shahar who really want to continue

to live here are forced by poverty to sell their homes and move

away. When they leave, this, too, contributes to altering the

character of the neighborhood. Their absence is felt by those

of us who remain and it is a great loss to us. I don't have anything

against new people moving here, but I would like them to care

about Ichari Shahar and not destroy its history.

All this major construction has occurred since we gained our

independence in late 1991. How ironical that at the exact moment

in time when we have the best chance to safeguard our own national

history, we are contributing the most to its destruction.

Warsaw

The greatest problem is that these new buildings are destroying

the character and face of Ichari Shahar. It doesn't have to be

this way. Consider Poland and the city of Warsaw. Because of

extensive bombing in World War II, the city was reduced to rubble.

Despite the enormous devastation, the city has been rebuilt and,

today, stands as a very beautiful city and a tribute to the human

desire to maintain links to the past. This restoration came because

of the commitment of government officials who employed artists,

historians and architects to ensure that the rebuilding effort

was in accord with the old gravures and watercolor sketches,

which documented what the city center, had previously looked

like. Warsaw was reconstructed, thanks to their hard labor and

love.

Today when you visit Warsaw, you think that these buildings were

actually constructed in the 15th-16th centuries, but they are

20th century reconstructions. The face of Warsaw has been kept

because the Polish people were committed to keeping their own

history. Krakow was rebuilt in the same manner.

Above: Mir Teymur is known

for his protest art. Here he is biting satire and critique of

society are molded into clay. The artist depicts upon some of

the characters familiar to him growing up in Baku's Old City.

Left to right: 1. Too small for position 2. No personality 3.

Empty Brain 4. The Gossip

Ichari Shahar today

But so many of our new buildings do not complement the character

of Ichari Shahar. Take, for example, the British Council, a building

of many stories with its façade of glass. It has no place

in our Old City beside a medieval bathhouse.

And how is it that Embassies have been allowed to establish their

governmental offices in this part of our city that is historically

reserved for private residential quarters. Presently, Ichari

Shahar is host to the embassies of Italy, Norway, Georgia, Greece

and Poland. Even for the safety of diplomats in this new age,

it is not a wise decision to settle there because there are only

a few streets that exit Ichari Shahar.

From the early days of independence, commercial interests set

their eyes on Ichari Shahar to set up offices there. BP and Statoil

Alliance was the first oil company to move there. Then other

oil companies followed: Amoco, AIOC (Azerbaijan International

Operating Company), NAOC (North Absheron Operating Company),

Pennzoil (now Devon), LUKoil, Agip, Mobil and Ramco. Now most

of these companies have moved out or have been dissolved. These

oil companies came to realize that their fantasy of working in

the Old City was a bad management decision because it brought

so much vehicular traffic to those narrow streets. Simply, the

infrastructure could not effectively support their own operation.

Today, many of these major companies have relocated elsewhere;

unfortunately other companies have taken their places, including

major international financial institutions.

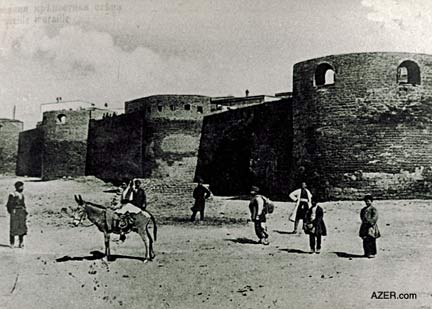

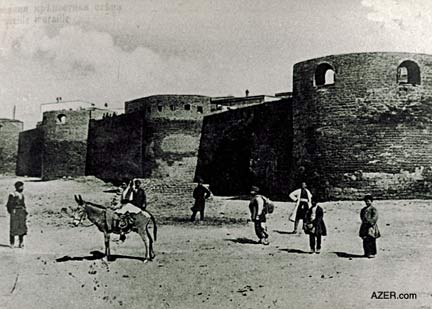

Left: Outside the Citadel walls, late 19th

century Left: Outside the Citadel walls, late 19th

century

I remember

when I was studying art in St. Petersburg (then Leningrad).

They had an excellent school where architects studied issues

related to historical restoration. Architects involved with the

design of buildings in Ichari Shahar must have a broad range

of knowledge and interests. In addition to architecture, they

should know the history, archaeology, ethnography and even folklore,

specific to this location as well. This land is a sacred, holy

place so it requires special sensitivities.

Not every person who has studied architecture should have the

right to design houses in the Ichari Shahar. Let them go to the

suburbs-the micro regions-where it doesn't matter as much if

they don't maintain the flavor and color of the past.

I'm not saying that construction should not take place in Ichari

Shahar. Not at all. There are many houses that are so old and

dilapidated. Such houses should be destroyed because they are

hazardous for people to live in. But the buildings which replace

them should be rebuilt in such a manner that they blend in with

the surrounding buildings. This is what is being done in St.

Petersburg. From the outside, buildings take on the appearance

and façade of the 17th or 18th century. Inside, the residents

enjoy every comfort of modern life: air-conditioning, heating,

lighting, design.

World Heritage

Site

In December

2000, UNESCO's (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

Organization) World Heritage Committee added Baku's Ichari Shahar

to its list of World Heritage Sites. At the time, this designation

had been extended to 690 historical and natural sites, which

they deemed, warranted protection so that they would be preserved

for future generations. The Great Wall in China, the Acropolis

and Yosemite National Park in California are on this list. In December

2000, UNESCO's (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural

Organization) World Heritage Committee added Baku's Ichari Shahar

to its list of World Heritage Sites. At the time, this designation

had been extended to 690 historical and natural sites, which

they deemed, warranted protection so that they would be preserved

for future generations. The Great Wall in China, the Acropolis

and Yosemite National Park in California are on this list.

According to UNESCO's Web site, Baku's Walled City was chosen

because it illustrated significant stages in human history: "Built

on a site that has been inhabited since the Paleolithic Era,

the Walled City of Baku reveals evidence of Zoroastrian, Sassanid,

Arabic, Persian, Shirvani, Ottoman, and Russian presence in cultural

continuity. The Inner City (Ichari Shahar) has preserved much

of its 12th-century defensive walls. The 12th-century Maiden's

Tower (Giz Galasi) is built over earlier structures that date

from the 7th to 6th centuries BC, and the 15th-century Shirvanshahs'

Palace is one of the pearls of Azerbaijani architecture."

Azerbaijan then became eligible to apply for assistance from

the World Heritage Fund and to receive help with conservation

and management of the site, training, technical cooperation and

assistance with educational, information and promotional activities.

Azerbaijan had already ratified UNESCO's Convention Concerning

the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage on

December 16, 1993. By signing this document, the country pledged

to preserve the historical sites situated on its territory. When

Ichari Shahar was added to UNESCO's World Heritage, Azerbaijan

specifically committed to protect the architectural integrity

of this part of our city.

Then came President Heydar Aliyev's Decree on February 17, 2003,

that construction within the Citadel Walls would not be allowed

unless it followed strict guidelines set forth for construction

there. But the decree went unheeded. Hardly two weeks had passed

before construction began again, at first, during the nighttime

though it is impossible to keep any secrets in Ichari Shahar.

Of course, there are a number of buildings that are between 100

to 200 years old that are collapsing. As well, there are a number

of homes that were constructed during the Soviet period that

were only meant to last for 10 years, but they have been standing

for 60 years. All of them should be replaced but certain criteria

and guidelines must be followed in the construction process.

Development for

the Future

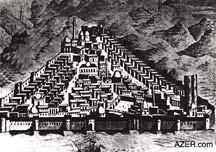

Left: Artist's rendition of Ichari Shahar,

18th century. Note that the citadel wall was separated the land

from intruders attacking from the sea. Left: Artist's rendition of Ichari Shahar,

18th century. Note that the citadel wall was separated the land

from intruders attacking from the sea.

During the past few years, I have collected nearly 1,400 signatures,

mostly from individuals who are living in Ichari Shahar, who

are concerned about the future development in their community.

Here are the major issues:

1. First of

all, buildings should comply with height regulations, meaning

that they should not exceed the historical limit of 11 meters-three

stories. The tallest buildings in Ichari Shahar never used to

exceed this height.

But today, there are quite a few buildings that rise to four

or more stories. This not only affects the visual appearance

of Ichari Shahar, but, in turn, it affects many other aspects

of the city plan as an organic whole.

For example, climatic control is altered. Taller buildings interrupt

the natural flow or channel of air and wind through the streets.

The taller buildings create strong down drafts. Taller buildings

mean a denser population in a section of town that already is

strained by excessive vehicular traffic, and utility infrastructure

related to supplies of water, electric and sewerage.

2. Experts should be consulted in a number of fields to guarantee

that each building is held in compliance with the spirit of the

Old City. These experts should include archaeologists, ecologists,

cartographers, seismologists and geologists, all of whom should

be involved early on in the design of any new construction. In

the past, these experts have not been consulted. Nor have public

photo or video records been kept to document each new building

location before, during and after construction.

3. Construction works should not be carried out with heavy construction

equipment such as excavators, bulldozers and heavy trucks. Our

Constitution demands that historical sites be protected. One

section of the law even prohibits the use of excavating equipment

in such areas.

But these safeguards are not in place. Consideration is not being

made for the layers of civilization that exist under the many

layers of soil; for example, natural springs, underground tunnels

and archaeological artifacts that date back centuries or even

millennia. Some of the new buildings have been constructed in

such a way that they are blocking natural underground water reservoirs.

In earlier times, people knew where these water resources were

located and they dug wells to access clean, cool water. We have

an expression in Azeri that declares that it's a sin to cast

anything into a well. But an even greater sin takes place when

you cover a water supply with rocks or soil. It's like cursing

your native land.

Above: 1&2.Inside view

of the citadel walls which shows how the wall was designed so

that the residents could defend themselves. 3. The Citadel wall

as viewed from Vahid Park nearby the Philarmonic Hall.

Foundations and pilings are being secured by dynamic percussion

works, which again affects underground settlement throughout

the area. Any percussion work carried out on a specific site

has the potential of harming the whole area. This is of particular

concern since the area is prone to earthquakes and landslides.

4. The new buildings are incorporating plastic materials that

are alien to the historical image of the Old City. The "red

lines", meaning the footprints of the buildings, have not

been adhered to and buildings are being expanding beyond the

original building lines. This diverts the natural and historical

patterns of pedestrian and car traffic. Streets that dead-end

have been created where they did not exist before. Again, this

affects the flow of air throughout the neighborhood.

Some buildings now have balconies that protrude beyond the building

façade and thus turn the walkways below into covered passages.

Again, this affects the climactic balance.

5. Archaeological evidence is being destroyed. When excavations

are being done for foundations, archaeological evidence, including

ceramic sewer pipes, underground galleries, tunnels and wells

have been found. Even if you use a spade or shovel to dig, and

if you come across an historical artifact or foundation, you

are required by law to consult with archeologists. They, in turn,

are supposed to judge if you will be allowed to continue your

work or not.

Not only is much of the evidence broken and destroyed during

the construction process, but also no archaeological records

are being made. Archaeologists are not being called to investigate.

Simply, any archaeological evidence that is found is quickly

covered, sometimes even with concrete. Not only does this result

in tremendous historical loss, but also it can affect the drainage

of subsoil water. The additional weight of many of these buildings

is cause for concern because of potential landslides.

6. New construction should be required to have billboards to

identify the design of the new construction. Without such documentation,

the works are likely to be carried out with numerous violations

for construction at a World Heritage site.

7. Often the renovation of the facades of the old buildings is

done with metallic brushes or with sandblasting equipment. This

results in the erosion of the stone surfaces.

These are the basic concerns of our community. The house in which

I live is more than 100 years old. It's a very warm, cozy place.

I don't mean "warm" in the physical sense, but rather

people are conscious of its comfortable, friendly atmosphere.

People who stop by this house even for just 10 minutes don't

want to leave. This is the secret of my house. It's the secret

of Ichari Shahar, too. You come and you want to stay for a long

time. That's what we are fighting so hard to preserve it.

From Azerbaijan

International

(12.3) Autumn 2004.

© Azerbaijan International. All rights reserved.

Back to Index AI 12.3 (Autumn

2004)

AI Home

| Search | Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|