|

Related articles 1 Albanian

Script: How Its Secrets Were Revealed? - Aleksidze and Blair

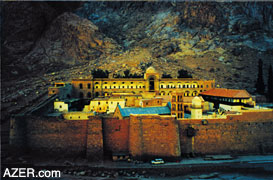

Above: (Left) St. Catherine's Orthodox Monastery on Mt. Sinai in Egypt was built in the 6th century. A fire led to the discovery and later decipherment of the unknown Caucasian Albanian script by Zaza Aleksidze. (Right): One of the most time-consuming tasks in deciphering the Albanian text was simply being able to make out the shape of the letters on the palimsest. Photo on left is with ultra-violet light. Letters on right were painstakingly copied by Aleksidze. Aleksidze's work is considered to be the foremost discovery related to Caucasian studies and one of the most significant finds this past century related to early man's writing systems. It wasn't that he went in search of an ancient alphabet to decipher; he stumbled upon this unknown script quite by chance while doing research on Georgian manuscripts. But he turned out to be the right person in the right place at the right time to identify and decipher this mysterious script. Aleksidze had spent a lifetime accumulating a phenomenal amount of knowledge about languages, historical geography, epigraphy, ancient church history and literature. And the combination of all these things together enabled him to crack the code of the Caucasian Albanian writing system. Fire on Mt. Sinai Ask librarians what they fear most when it comes to protecting their valuable book collections. Inevitably, at the top of their lists is concern about fire. After all, some of civilization's greatest library treasures have been destroyed by fire - from Alexandria, Egypt, in the 1st century B.C., to the Central Library in Baghdad, Iraq, in Spring 2003.  Who would ever have imagined that precisely because of a devastating fire, an ancient writing system would be discovered? Such is the case of the written language of Caucasian Albanian, ancestor to the contemporary Udi language, which is spoken by a population of about 8,000 ethnic Udins, who primarily live in Azerbaijan. This story of decipherment begins quite some distance from the Caucasus Mountains in what might seem to be the most unlikeliest of places - the remote desert mountains of Mt. Sinai, Egypt, after a fire broke out there at St. Catherine's Orthodox Monastery. The date: May 26, 1975. While assessing the fire's damage, much to their surprise, the brethren at the monastery discovered a cellar room underneath the chapel floor where hundreds of centuries' old manuscripts had been stored. The monks didn't even know that such a room existed. The chapel floor, which had been constructed of wood, had been firmly packed down with earth. When the floor collapsed during the fire, the earth fell on top of the manuscripts. In fact, it may well have been the earth itself that smothered the manuscripts and provided a sort of fire protection preventing the pages from being consumed and turned into ash. Later scholars would catalog the cellar collection and discover more than 1,100 manuscripts, dating from between the 4th-18th centuries. The majority of texts were Greek (approximately 800) and Georgian (141), but they also included Arabic, Syrian, Slavonic, Latin and Hebrew. More than 20 years would pass before anyone would discover that the collection held an even deeper secret - evidence of a script that nobody knew with any certainty even existed - Caucasian Albanian. The Hidden Cellar How is it that so many ancient manuscripts were stored away in a hidden cellar? How could the monks have possibly forgotten about its existence? No one knows for sure, but it seems that about 250 years earlier, in 1734, Archbishop Nikiphoros Marthalis had organized for the construction of a new library at St. Catherine's. He then arranged for the monastery's manuscripts to be transferred and stored there. Could it have been that the monks had left some of the older manuscripts behind, especially those that were severely damaged or of little practical everyday use? In 1761, a pilgrim by the name of Donati visited St. Catherine's and noted that in addition to the manuscripts that were so dearly treasured and well preserved in the library, others, stored elsewhere, were molded and neglected. He sensed that the monks themselves had forgotten about them. The discovery of so many unknown manuscripts was sensation at the monastery, but the monks were afraid traders might attack or assault them, so they vowed to keep it a secret. It would be five years before the news about the ancient manuscripts reached the press. In 1980, Mother Philotea, a member of another monastery in the complex at Mt. Sinai, addressed a symposium in Goslar, Germany, and spoke about the discovery of some Armenian manuscripts, among which were some Georgian works. In turn, German Orientalist Julius Asphalg, who was a well-known Georgian specialist, contacted Akaki Shanidze, distinguished Georgian scholar and director of the modern linguistic school in Tbilisi. But not until 1984 - nine years after the fire - did scholars in Tbilisi obtain more specific information. The Orthodox Patriarch of All Georgia, Ilia II, then visited Sinai and determined that the newly discovered manuscripts were not Armenian, as had been announced at the symposium; but rather, Georgian. Naturally, the Georgian Patriarch contacted the scholars at Tbilisi's Institute of Manuscripts and invited them to make an expedition to Egypt. At the time, the Institute was directed by the well-known scholar Academician Helen Metreveli. She was elderly at the time, so traveling to Egypt was considered difficult. Also they had heard a rumor that women were not allowed in the monastery - information that turned out to be untrue. Preparing for Sinai At the end of 1988, Dr. Zaza Aleksidze was appointed as Director of Institute of Manuscripts. From the early days of his appointment, he began making preparations to visit Sinai. Even so, organizing for such a trip was complicated. The unstable political situation in the Middle East aggravated the situation, making it unpredictable and difficult to plan. There were also difficulties in obtaining visas; much less, funding. In 1990 the Soviet Union was in a severe economic situation. The USSR would collapse the following year. Nor did it make much sense to visit St. Catherine's if they could not meet there with the Greek Archbishop who held jurisdiction over the monastery as they would need his permission to carry out research on the Sinai manuscripts. They discovered that he spent most of his time in Athens. Communication was slow and cumbersome. Those were the days before e-mail and the Internet, and the Manuscript Institute didn't even have access to a Fax machine. Eventually, they were able to connect with the Soviet Embassy in Egypt, which helped them tremendously in organizing that first expedition. After several failed attempts, they were finally able to make the first of what, so far, has been four working expeditions to Sinai (1990, 1994, 1996 and 2000). Since then, relations have been established with the Greek Orthodox Archbishop and the monks living at the monastery, and contacts have become much easier. St. Catherine's Monastery Actually, Sinai is really a complex of monasteries (Sinai, Firan and Raithu). However, whenever reference is made to "Sinai", it implies St. Catherine's, which is the main Orthodox monastery and dates back to the 6th century. The Georgian presence has been marked at Sinai since the early Middle Ages. Georgians seem to have played a dominant role since the second half of 10th century when a number of chapels and complexes were built by Georgian kings. Sources indicate that the names of the first two Georgian monks to live at Sinai were Mikhail and Eustatheus (6th century). Today, there are about 20 Orthodox monks residing at Sinai, though the number varies from time to time. They tend gardens there. The Bedouins work for them. Income for the monastery comes from hotels (outside the monastery wall), the enormous number of tourists, donations during Holy Days and from Orthodox religious communities. The monks are mostly Greek although a number of them come from various other countries, including Australia, the U.S. and U.K. There are even some Orthodox Jews from Russia. The Greek monks at Sinai had never even heard anything about the Caucasian Albanian language. In the beginning, they even mistook the Georgian manuscripts as Armenian. There are no Georgian monks on Sinai today. Had there been, still they likely would have had difficulty reading the old Georgian manuscripts without special training because the Old Georgian script looks so much different from the modern script. Though the Georgian script has changed over the millennia, the language itself has remained much the same. Prior to the fire, Sinai was known for a significant number of very important ancient Georgian manuscripts. After the fire, this remote monastery become known as a great repository and treasury for Caucasian and Georgian studies. First Expedition (1990) The journey to Sinai via the desert wilderness from Cairo takes about eight hours by car. Fourteen years after the fire had taken place, the Georgian experts finally had arrived. During that first expedition to Sinai (1990), the work was divided between Aleksidze and his Deputy Director at the Tbilisi's Manuscript Institute, Mikhail Kavtaria. They only had 13 working days to get an overview of the situation and begin compiling the rather extensive, though preliminary, catalog of the Georgian manuscripts. While Kavtaria concentrated on identifying the numerous liturgical texts, Aleksidze began describing the historical, hagiographical, patristic and Biblical manuscripts. He also examined and copied all the colophons - commentaries that scribes traditionally wrote at the end of the manuscript or in the margins, offering their own opinion about the content of the manuscript or historical events that had occurred while they were copying the text. These colophons which they found in the Georgian manuscripts are treasured for their rare insight into the history of Georgia and the Sinai monastery. Aleksidze also was curious to define the languages and scripts on parchments that had more than one text, which are known as "palimpsests" (from the Greek words, "palim" and "psito" - "to cook again"). The monks were in the habit of recycling and conserving material. Typically, when they didn't have anything on which to write, they would take an old manuscript for which they had little use anymore (or which was ideologically outdated) and try to scrub off the ink and reuse the manuscript. Afterwards, they would introduce new text, sometimes by writing perpendicular to the original script. It seems that during the 10th century, there was quite a shortage of parchment at Sinai. Some of the monks even complained about this shortage in their colophons. [For more details about palimpsests, see the side bar: "Questions & Answers: Deciphering the Albanian Script"]. More often than not, Greek or Ethiopian, Syrian or occasionally Armenian texts comprised the original script underneath the Georgian. Aleksidze was quite familiar with palimpsests as there are about 5,000 pages kept at Tbilisi's Institute of Manuscripts. On that first expedition, Aleksidze took an interest in the original layer of one of the palimpsests, which was barely legible and had rather unusual lettering. He made a note that the lower text might possibly be Ethiopian. As he only saw this script the last day, there wasn't much time to study it seriously. At the conclusion of their first expedition, Aleksidze and Kavtaria had succeeded in describing 130 manuscripts, but their work wasn't done. Because of the intense heat of the fire, some of the parchment manuscripts - 17 in total - had solidified, making the pages clump together and impossible to separate. The only way they could identify the texts was by their first folio pages, but it was impossible to read the actual contents. Soon they realized that another trip to St. Catherine's would be necessary to finish cataloging what had come to be known as the New Georgian Collection and which would eventually include 141 manuscripts and 10 scrolls plus a significant number of fragments, all dating from the 9th-13th centuries. Second Expedition (1994) The second expedition would not take place until four years later. The fact that the Soviet Union had collapsed in the meantime, further complicated the situation, making funding even more difficult. But on this expedition, Aleksidze brought along a scholar, I Khevuriani, who was a specialist in liturgy and Holy script, a photographer and three specialists who worked as conservators to soften and to open all the manuscript pages. In the last hours on that expedition, they managed to open a manuscript that turned out to be another palimpsest. Though the scribes had done an incredible job of scrubbing off the ink of the original text; ironically, the high temperature generated by the fire had made the letters of the lower text layer even more visible. When the conservators showed Aleksidze this manuscript, again some of those strange letters reminded him the palimpsest the lower layer of which he thought might be Ethiopian. This time it was clear for him that some of the letters also resembled Georgian and Armenian letters. This fact also made him conscious that he might be dealing with a text in Caucasian Albanian. As this second palimpsest had been discovered again at the last minute almost as they were heading out the door, Aleksidze didn't even have time to copy down a few letters. Another expedition would be necessary. Search for Albanian Alphabet The search for a written form representing any of the Caucasian Albanian languages can be traced to the 1930s. Mostly Armenian and Georgian scholars were delving into the problem. Azerbaijani scholars were not involved much, prior to the archeological discoveries in Mingachevir (in north central Azerbaijan) between 1948-1952. On several occasions, scholars announced that they have found Albanian manuscripts and epigraphic monuments. These were sensational discoveries for Caucasian studies, but the news inevitably proved to be premature. The texts always turned out to be written in some unknown manner, usually based on Armenian or Greek scripts. Sometimes, the scripts even turned out to be cryptograms. When there seemed little hope of finding a single sample of the Albanian alphabet, Georgian scholar Ilia Abuladze (1901-1968) discovered a sample of the Albanian alphabet in an Armenian grammar text dating to the 15th century, side by side with various other alphabets such as Armenian, Greek, Hebrew, Georgian, Coptic, Syrian and Arabic. This discovery made such an impact in the world of scholarly literature on the subject that the date - September 28, 1937 - was memorialized. The Armenian scholar Hrachya Atcharyan wrote in the Herald of the Armenian Academy of Sciences: "The young Georgian scholar Ilia Abuladze, who discovered the Albanian alphabet on September 28, 1937, among the manuscripts of Echmiadzin, is worthy of inestimable honor and praise". Atcharyan also compared this discovery of the Albanian alphabet to a man suddenly being exposed to daylight after living in darkness for ages. But Abuladze only announced the discovery, he didn't study the text, leaving that job for Akaki Shanidze (1887-1987), head of the Georgian School of Linguistics. The principal problem for Shanidze was to prove that the reference actually did represent the Albanian alphabet. He confirmed the relationship and then went on to identify the alphabet with the Udi language, a Lezgian group of Caucasian languages, spoken by the Udins who live primarily in northern Azerbaijan. These archaeological discoveries led scholars to believe that the Albanian texts would be deciphered easily, as the script represented the Udi language, a living language with a corresponding sound structure, which was available. Specialists from a number of countries were involved in trying to decipher the inscriptions. But the promise was never fulfilled. The problem was that each specialist always began his research from the beginning, rather than building upon the observations that predecessors had already made. Despite minor successes in deciphering of Albanian inscriptions, essentially all attempts failed. The fact that there was no long and continuous text made it impossible to study various data. Third Expedition (1996) Two more years passed before the third expedition could be arranged. In 1996 Aleksidze headed back to Sinai with two conservators and four scholars including the daughter of Akaki Shanidze, who is a specialist in the Holy script herself. Her father had been the first to link the Udi language with the Albanian. Aleksidze also took along the photos of the Albanian alphabet from the Armenian manuscript and from the Mingachevir archaeological inscriptions. On the very first day he compared them with the two palimpsests. This time he was convinced that the lower text on the palimpsest was, indeed, Albanian. It was at this point that he revealed everything to his colleagues who affirmed his hypothesis. He spent the majority of December just trying to be able to make out the shape of the letters of the script and copying some small, more visible sections of the text since the 10th century monks had done such a conscientious job of trying to wipe out that text. In most cases, photographs proved to be even less effective than the naked eye. Ultraviolet lamp was helpful, but still limited. Fourth Expedition (2000) The final working expedition undertaken so far took place four years later when Aleksidze took along art historian David Tshkadadze, a photographer, and his own son Nikolas (Tato) who had developed a keen interest in classical studies and ancient scripts. This time they busied themselves with photographing all 300 pages of the to Georgian / Albanian palimpsests using ultraviolet light which helped to expose the original layer of text more clearly. Aleksidze copied the entire text that was visible under the ultraviolet light. They would return to Tbilisi to develop the film and Aleksidze would begin the decipherment process. In early 2001, back in Tbilisi, Aleksidze finally was able to begin deciphering the first words of the manuscript that had consumed so much of his time during the past decade [see Decipherment sidebar]. Finally, the Caucasian Albanian script was beginning to speak to him. Since then, he has been able to identify its contents as being a very early Albanian Lectionary which celebrates the church calendar, making it one of the earliest Lectionaries that exists in the world today. Still an immense amount of work must be done before all the texts can be clearly seen and deciphered. More sophisticated equipment is needed to view the palimpsests. However, already the implications for further research in many fields are evident, especially in Caucasian studies, Biblical and liturgical studies, as well as linguistics. The next decade should prove to be one of many more discoveries - all of which were given birth in a devastating fire in a monastery in the desolate mountains of Egypt a quarter of a century ago. Various people who have made an enormous contribution to this project during this past decade. They include: His Eminence Archbishop of Sinai Damianos, Librarians Father Dimitrios and Father Simeon of St. Catherine's Monastery, and all the monastery brethren for their never-failing support and hospitality of Dr. Aleksidze and the Georgian researchers. Without the painstaking efforts of David Tskhadadze, who was involved in developing the film for all the palimpsest pages, decipherment would have taken so much more time. For this article, George Aleksidze, 14, son of Zaza Aleksidze prepared all the computer photos and illustrations of the Albanian text. Contact Dr. Zaza Aleksidze,

Director of Tbilisi's Institute of Manuscripts: zaza_Alexidze@hotmail.com. Back to Index

AI 11.3 (Autumn 2003) |