|

Summer 2002 (10.2)

Voices of the Ancients

Heyerdahl

Intrigued by Rare Caucasus Albanian Text

by Dr. Zaza Alexidze

Other articles

related to Thor Heyerdahl:

(1) Thor Heyerdahl in Azerbaijan: KON-TIKI

Man

by Betty Blair (AI 3:1, Spring 1995)

(2) The Azerbaijan Connection: Challenging

Euro-Centric Theories of Migration by Heyerdahl (AI 3:1, Spring 1995)

(3) Azerbaijan's

Primal Music Norwegians Find 'The Land We Come From' by Steinar Opheim (AI

5.4, Winter 1997)

(4) Thor

Heyerdahl in Baku

(AI 7:3, Autumn 1999)

(5) Scandinavian

Ancestry: Tracing Roots to Azerbaijan - Thor Heyerdahl (AI 8.2, Summer 2000)

(6) Quote:

Earlier Civilizations - More Advanced - Thor Heyerdahl (AI 8.3, Autumn 2000)

(7) The

Kish Church - Digging Up History - An Interview with J. Bjornar Storfjel

(AI 8.4, Winter 2000)

(8) Adventurer's

Death Touches Russia's Soul - Constantine Pleshakov (AI 10.2,

Summer 2002)

(9) Reflections on Life

- Thor Heyerdahl (AI 10.2, Summer 2002)

(10) First Encounters in

the Soviet Union - Thor Heyerdahl (AI 10.2, Summer 2002)

(11) Thor Heyerdahl's

Final Projects - Bjornar Storfjell (AI 10.2, Summer 2002)

_____

Much of the territory of modern

Azerbaijan was once known as Caucasus Albania - not to be confused

with the modern country of Albania found in the Balkans. Caucasus

Albania remained a cohesive, mostly Christian, political entity

in the area from the third to eighth centuries A.D. But even

though the ancient Albanians were highly advanced and had their

own writing system, very few remnants are left from their civilization.

A few Albanian inscriptions were found in Azerbaijan in 1948-49

during an archeological excavation, but until recently, no one

could figure out how to decipher them.

According to Professor Zaza Alexidze, one of the world's top

experts on the Caucasus Albanian period, some amazing progress

has been made on this front in the past few years. His remarkable

discovery of a rare Albanian church service book even attracted

the attention of the late Thor Heyerdahl, who was very interested

in the possibility that the ancient Caucasus Albania region was

the original home of the Scandinavian ancestor Odin. Heyerdahl,

unlike many other scholars, took Odin to be a real person who

migrated to the region from the Azerbaijan region, not just a

mythological character.

______

Dr. Thor Heyerdahl was a legendary personality for the teenagers

of my generation living in Georgia. We were fascinated by his

books and films. I'm sure that for many of us, his example influenced

our career choices and academic directions. As for me, I decided

to specialize in the study of ancient texts. Today I am the Director

of the Institute of Manuscripts in Tbilisi, Georgia.

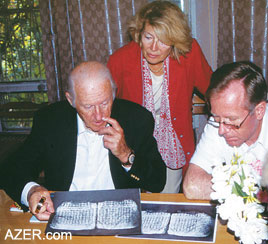

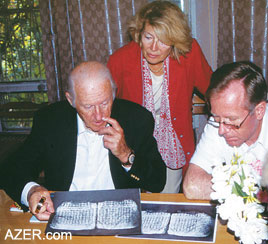

Left: Thor Heyerdahl examines a text at the

Institute of Manuscripts in Tbilisi, Georgia, during his September

2000 visit.

Right: Thor Heyerdahl, Thor's wife Jacqueline,

and archeologist Bjornar Storfjell examine copies of the ancient

Caucasus Albanian church service book at the Institute of Manuscripts

in Tbilisi, Georgia.

So you can imagine my joy when I heard that Thor Heyerdahl wanted

to pay a visit to the Institute of Manuscripts to see me. His

visit was one of the most interesting and important days of my

life.

Heyerdahl was convinced that the Scandinavian god Odin was actually

a historical figure who had originated from the Caucasus and

then migrated with large numbers of his people to Scandinavia.

Heyerdahl's search for the traces of Odin had taken him to Azerbaijan

to find out more about the Udis, a small Christian minority living

there.

The Udis' ancestry and language dates

back to the highly developed Caucasus Albanian population that

used to live throughout the region prior to the 10th century.

After that time, the Caucasus Albanian state, people and culture

gradually vanished from the historical arena. Today the few thousand

remaining Udis live in three villages: Nij and Oghuz (previously

Vartashen) in Azerbaijan and Zinobiani in Georgia. The Udis' ancestry and language dates

back to the highly developed Caucasus Albanian population that

used to live throughout the region prior to the 10th century.

After that time, the Caucasus Albanian state, people and culture

gradually vanished from the historical arena. Today the few thousand

remaining Udis live in three villages: Nij and Oghuz (previously

Vartashen) in Azerbaijan and Zinobiani in Georgia.

Important Discovery

Some scholars believed that the Caucasus Albanians in this area

never had their own written language and alphabet. All known

Albanian texts had been preserved only in the Armenian language.

But in 1996, I discovered an ancient manuscript that proved conclusively

that Caucasus Albania once had its own highly developed written

language. During an expedition to St. Catherine's monastery on

Mt. Sinai in Egypt, I found a unique palimpsest, a type of parchment

manuscript that has two layers of text. The top layer of text

was Georgian, but beneath it was another layer - this one, written

in Albanian script.

Back in the Early Middle Ages, parchment was very expensive and

in great demand, so it was typical for manuscripts to be reused.

In this particular manuscript, the lower Albanian text was washed

away so that the 10th-century Georgian text could be written

on top of it. That makes the lower-layered Albanian text very

difficult and time consuming to read, but with the help of modern

technology and special illumination, we can determine what it

says.

When Heyerdahl visited me in Tbilisi

in September 2000, he was very curious to learn more about my

discovery. I showed him several photos of the palimpsest and

some of the pages that I had copied from it. We had a long talk,

exchanged views and spoke about future joint plans. He also visited

the repository of the Institute of Manuscripts, which contains

a large number of ancient manuscripts and historical documents

in Georgian and many other languages. When Heyerdahl visited me in Tbilisi

in September 2000, he was very curious to learn more about my

discovery. I showed him several photos of the palimpsest and

some of the pages that I had copied from it. We had a long talk,

exchanged views and spoke about future joint plans. He also visited

the repository of the Institute of Manuscripts, which contains

a large number of ancient manuscripts and historical documents

in Georgian and many other languages.

My work of deciphering the lower layer of the Georgian-Albanian

palimpsest continued until the beginning of 2001. Unfortunately,

I never had another chance to see Heyerdahl, and I'm not sure

if he heard about the preliminary results of my work. My upcoming

book, which documents the results of deciphering the Albanian

manuscript, will be dedicated to Dr. Thor Heyerdahl's sacred

memory.

Ancient Lectionary

The palimpsest, as it turns out, is from a Christian Albanian

lectionary, a church service book that contained a collection

of liturgical lessons that were read throughout the church year

and mainly consisted of readings from the Old and New Testaments.

To compile a lectionary, one must first have a translation of

the Bible available in that language.

This Albanian lectionary is very simplified, with only readings

for 12 religious feasts along with some psalms and praises (alleluias).

Unlike other ancient lectionaries, there is no evidence of a

calendar system, no mention of any saints or ecclesiastical Fathers

and nothing about liturgical processions to the holy places in

Jerusalem and stops at relevant churches.

Traditionally within the church, lectionaries

have evolved from being very simple to more and more complex.

This means that in all probability, the Albanian text represents

one of the first lectionaries ever written. It may even date

back to the second half of the 4th century. In turn, that would

mean that the written Albanian language had been created even

earlier. Traditionally within the church, lectionaries

have evolved from being very simple to more and more complex.

This means that in all probability, the Albanian text represents

one of the first lectionaries ever written. It may even date

back to the second half of the 4th century. In turn, that would

mean that the written Albanian language had been created even

earlier.

It's also interesting to note that some of the lessons given

in the Albanian lectionary are not found in ancient Armenian

and Georgian lectionaries. This may indicate that the Albanian

lectionary was not translated from those other languages but

was composed independently based on a Greek lectionary, which

no longer exists.

Lost for Centuries

So why did the Albanian script disappear in the first place?

In the 8th to 10th centuries, Arab invaders and Armenian clerics

burned documents that were written in the Albanian language.

The Albanian Church until around 720 AD was Diophysite, meaning

that it perceived Christ as having a dual nature - both human

and divine. The Armenian Church, however, was Monophysite and

believed that Christ's nature was altogether divine. It wanted

to stamp out any literature that was considered to be Diophysite.

From about 720 onwards, the Albanian church was strongly affected

by the influence of the Monophysite Armenian Church. Albania

gradually adopted the Armenian language and script, and thus,

step by step, lost its national identity and written language.

Up until recently, the only Albanian historical and ecclesiastical

texts we had access to were translations that had been preserved

in the Armenian language.

By examining the language found in the

palimpsest, I discovered that the direct descendants of the Albanian

people, the Udis, still speak a language that is very similar

to the ancient Albanian language. Up until recently, the Udis

wrote their language in the Cyrillic alphabet; now that Azerbaijan

has opted for a Latin-based script, they, too, have switched

to the Latin alphabet. But neither alphabet can handle the 50

or more phonemes found in the Udi language without creation of

additional symbols. [As of this writing, the work on the Udi

grammar has not yet been finished. Some scholars identify 52

letters, some 54, others 48]. Perhaps this new discovery will

mean that the Udis can reclaim their long-forgotten alphabet

once again. By examining the language found in the

palimpsest, I discovered that the direct descendants of the Albanian

people, the Udis, still speak a language that is very similar

to the ancient Albanian language. Up until recently, the Udis

wrote their language in the Cyrillic alphabet; now that Azerbaijan

has opted for a Latin-based script, they, too, have switched

to the Latin alphabet. But neither alphabet can handle the 50

or more phonemes found in the Udi language without creation of

additional symbols. [As of this writing, the work on the Udi

grammar has not yet been finished. Some scholars identify 52

letters, some 54, others 48]. Perhaps this new discovery will

mean that the Udis can reclaim their long-forgotten alphabet

once again.

Unto the Unknown

Now there is no doubt that the Caucasus Albanians once had their

own written language and literature. But many questions remain:

When was the Caucasus Albanian state formed on this territory?

How far did it spread? How did the process of ethnic and cultural

consolidation develop there?

Up until recently, the only information we had about the Albanian

language came from Armenian sources. But now, this discovery

will enable us to have access to less biased sources about the

history of Albania, which may even reshape our ideas about ethnic

origins and the history of the Albanian nation. An unknown civilization

is revealing itself to us through its ancient alphabet.

Dr. Zaza Alexidze is the Director

of the K. Kekelidze Institute of Manuscripts of the Georgian

Academy of Science (1989-) and Head of the Armenology Department

at Tbilisi State University (1979-). Contact: Dr. M. Alexidze,

Institute of Manuscripts, Street 1, Bild 3, Tbilisi 380003, Georgia.

Tel/Fax: (995-32) 94-25-18.

Email: zaza_alexidze@hotmail.com.

______

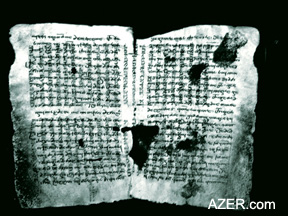

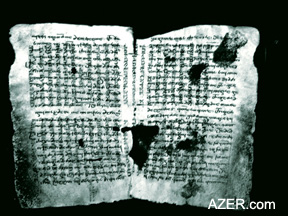

From the Caucasian Albanian text found

in one of the palimpsests at the Mt. Sinai monastery (Egypt).

This segment was identified by Dr. Zaza Alexidze, as II Corinthians

11:26-27 in which the Apostle Paul provides a short autobiographical

summary of what he has suffered to proclaim about Christ. The

Living Bible Translation reads: From the Caucasian Albanian text found

in one of the palimpsests at the Mt. Sinai monastery (Egypt).

This segment was identified by Dr. Zaza Alexidze, as II Corinthians

11:26-27 in which the Apostle Paul provides a short autobiographical

summary of what he has suffered to proclaim about Christ. The

Living Bible Translation reads:

(26) "I have traveled many weary miles and have often been

in great danger from flooded rivers, and from robbers, and from

my own people, the Jews, as well as from the hands of the Gentiles.

I have faced grave danger from mobs in the cities, and from death

in the deserts, and on the stormy seas, and from men who claim

to be brothers in Christ, but who are not.

Right:

A page of the Caucasus Albanian-Georgian

palimpsest discovered by the author at Mt. Sinai. In the 10th

century, the Caucasus Albanian writing was partially washed away

from the parchment, and then a Georgian text was written perpendicular

to it.

(27) I have lived with weariness and pain and sleepless nights.

I've often been hungry and thirsty and have gone without food;

often I have shivered in the cold, without enough clothing to

keep me warm."

To see Detailed Notes on the

Grammar of this Biblical passage (II Corinthians 11:26-27) in

Caucasian Albanian text by Dr. Zaza Alexidze, visit: www.lrz-muenchen.

de/%7Ewschulze/Cauc_alb.htm#gram. To see: "A Functional

Grammar of Udi" by German Professor Dr. Wolfgang Schulze

of the University of Munich, visit: www.lrz-muenchen.de/~wschulze/FGU.htm.

____

Back to Index

AI 10.2 (Summer 2002)

AI Home

| Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|