|

Beyond the Russian

Language

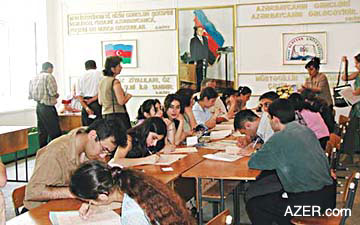

Above: Card catalogs are still the norm at many of Azerbaijan's libraries, including this one at Baku Slavic University. For the past year, we have been working hard to establish many new departments at the University. In the past, we only had one faculty for teaching Russian. It was divided into two sections: a section for students who had graduated from Russian-track schools and another section for those who came from Azeri-track schools. However, if the Institute had continued to teach only the Russian language, I think it would have eventually become irrelevant and eventually disappeared. More Languages Today, the University's choices are much broader. We have faculties of Philology and Pedagogy. Our Regional Studies faculty gives students the opportunity to study economics, international relations or primary education. For those teachers who have decided to change their specialty and return to the university to study Slavic languages, we have a faculty for Advanced Studies and Requalification.  In addition to Russian language and literature, Baku Slavic University offers specialties in Ukrainian, Polish, Czech, Bulgarian and Slovak language and literature. We need to teach as many Slavic languages and literatures as we can; in the future I hope that we'll be able to teach all of them here. It may surprise you that we also offer Greek language and literature as a specialty, even though it's not a Slavic language. But I view "Slavic University" as a symbolic name. It doesn't prevent us from teaching Turkic, Japanese, Chinese, Korean or even African languages in the future, if we so choose. In my opinion it's not enough to study a specific system like Slavic Languages and cultures; you should know something about the systems that surround such a specialty as well. Training Azeri Teachers There's another twist to our program as well. We train Azeri teachers for Russian-track and English-track schools - another innovation. In the past, most of the children who attended Russian-track schools could not speak Azeri very well. The Azeri teachers at those schools were not strong enough, so the children took little interest in the subject. Today when I ask students who were educated in Russian-track schools: "Why is your Azeri so poor?" they reply: "Because we weren't taught Azeri well." If Azeris teaching at Russian schools are stronger than Azeris teaching at Azeri schools, to some extent, the credit belongs to our university. That's why today we want to strengthen Azeri in Russian schools now. In the future, teachers who are trained here will not only be able to teach Azeri; they will also know Russian, another Slavic language and English. For example, if a student's specialty is the Czech language, he or she is also taught Azeri, Russian and one of three Western European languages - English, German or French. Even though English is not a specialty here, the truth is that our students spend more hours studying in English classes each week than students at other universities who concentrate in English as their specialty. Exchange Programs My biggest dream is for teachers and students to master the language and culture of their specialty, not through books, but by being able to go and live in that country. We consider it an important part of our University's mission to promote student exchange programs. We're just in the beginning stages. So far I've already been to Jagiellonian University in Krakow, Poland. We're also trying to build relations with Charles University in the Czech Republic and the National Institute of Oriental Culture and Languages (INALCO) in France. We have already developed relations with institutions like International Academy of Personnel in France, Institute of Russian Language after Pushkin in Russia, Moscow State University of International Relations in Russia, Cherkas State University in Ukraine and Slavic University in Kiev. Afterward, we want to organize student and teacher exchanges with these schools and participate in regional conferences and meetings as well. Last summer, for the first time, we sent 18 students for one month of pedagogical practice at Cherkas State University in Ukraine. We're also planning to send two students to the Czech Republic this year. My biggest dream would be to send our first and second year students of Czech to continue their studies and receive a master's degree from the University of Prague. Then they could return and teach Czech here. There are a lot of other proposals for exchanges, but because of the financial limitations, we can't respond to all of them. Of course, if we send our students to Prague and other places, we have to be prepared to receive foreign students here. What can we offer them? That's why I've established a Chair of Turkic Languages Study and a laboratory for Turkic-Slavic Relations. We would like to offer these foreign students the chance to study Turkic languages like Azeri and Turkish as well as Turkic literature and the history of Turkic peoples. So far, we've had foreign students come from Turkey, Iran and Korea. They learn Azeri here through Azeri, not Russian. We also have Russian and Ukrainian students living in Azerbaijan and learning Azeri. Challenges With the rapid growth of the school and the addition of new programs, we have seen our enrollment increase to more than 2,000 students. Today, many more students are writing Baku Slavic University at the top of their lists when they take their entrance exams. Yet, we still struggle with many difficulties. One of the most pressing, obviously, is financial. I would like to repair this building, to make it more beautiful. We also have problems getting hold of textbooks; many of the ones we have were published during the Soviet era and are now outdated. But it's difficult to acquire new books. When I went to Poland, I brought back a whole suitcase of books for learning Polish. When starting relations with any other university, we talk about book exchange first of all. We're also concerned about teachers. The salary that they receive from the government is so minimal that we give them extra aid each month. Right now we have about 400 professors, assistant professors and teachers, about 50 professors and doctors, 130 candidates of sciences and assistant professors and teachers. We also give aid to our 500 technical workers and laboratory assistants. My goal is also to improve the relations between students and teachers. I would like all of our teachers to treat students like colleagues, rather than inferiors. When I address students, I say "my colleagues". I realize this confuses some of my teachers. My personal slogan is "Docento Distimus." In Latin it means: "By teaching, I learn." This is what I want to put into practice here - an attitude of learning on the part of all of us. Kamal Abdullayev,

Rector of Baku Slavic University, is both a Turkologist and a

dramatist. He also serves as President of Azerbaijan's Cultural

Fund. His recent works include: "The Theoretical Problems

of Azerbaijan's Syntax", and "The Secrets of the Silver

Period" (Russian poetry translated into Azeri). Currently,

his play called "Spy", based on some of the motifs

in Dada Gorgud, is being performed at the Azerbaijani National

Drama Theater. He is also known for his play, "The Mysterious

Dada Gorgud". Back to Index

AI 9.4 (Winter 2001) |