|

Winter 2001 (9.4)

Pages

46-49

On Our Own

Rebuilding

Azerbaijan's Aerospace Industry

by Arif

Mehdiyev

The Soviet Union had been such

a strong state that for many of us it came as a shock that it

could collapse. Since Azerbaijan's aerospace industry had been

completely financed by the Ministry in Moscow, it was as if we

had been suddenly orphaned. The Soviet Union had been such

a strong state that for many of us it came as a shock that it

could collapse. Since Azerbaijan's aerospace industry had been

completely financed by the Ministry in Moscow, it was as if we

had been suddenly orphaned.

When

the Soviet Union collapsed in late 1991, many of Azerbaijan's

established industries had to start all over again from scratch.

The aerospace industry was no exception. All of a sudden, Azerbaijan's

National Aerospace Agency - which had been given a generous budget

as part of the superpower's huge military buildup - was broke.

It didn't even have the funds to pay its own employees.

Here Dr. Arif Mehdiyev, the Agency's General Director, tells

how he and his colleagues restructured the organization after

it lost direction and funding from Moscow as well as its links

with other aerospace organizations throughout the Soviet Union.

Today the Agency focuses on remote sensing technologies that

have practical applications for fields such as agriculture, ecology

and the oil industry.

Azerbaijan's aerospace industry began in 1973, when Baku hosted

a meeting of the International Astronautical Federation (IAF).

It was the first time that such an event had ever been held in

the Soviet Union. About 2,000 representatives from all over the

world attended the Congress, including American astronaut Charles

Conrad, Jr.

At that time, Heydar

Aliyev was First Secretary of the Central Committee of Azerbaijan,

the top leadership position in the Republic. After the IAF Congress,

Aliyev challenged Azerbaijan's Academy of Sciences to realize

some sort of benefit from the advances in science and technology

that had been discussed at this important international meeting.

The organization decided to open the Scientific and Industrial

Association of Space Research, now known as the National Aerospace

Agency. This center officially opened in January 1975 under the

umbrella of Azerbaijan's Academy of Sciences. At that time, Heydar

Aliyev was First Secretary of the Central Committee of Azerbaijan,

the top leadership position in the Republic. After the IAF Congress,

Aliyev challenged Azerbaijan's Academy of Sciences to realize

some sort of benefit from the advances in science and technology

that had been discussed at this important international meeting.

The organization decided to open the Scientific and Industrial

Association of Space Research, now known as the National Aerospace

Agency. This center officially opened in January 1975 under the

umbrella of Azerbaijan's Academy of Sciences.

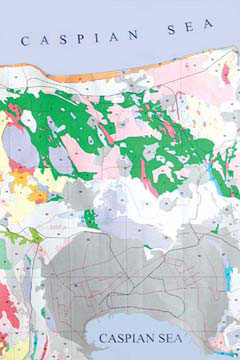

Left: In a project that was

the first of its kind for the former Soviet Union, Azerbaijan's

National Aerospace Agency worked with the UN Food and Agriculture

Organization to compile intricate maps of Azerbaijan using satellite

data.

Most other Soviet republics didn't have this type of aerospace

organization, or if they did, it was staffed mainly by Russian

scientists. For example, in the small institute that was established

in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, most of the workers were Russian. After

the Russian Federation and Ukraine, Azerbaijan became one of

the first Republics to have an organization of this kind.

In 1985, the association came under the authority of the USSR's

General Machinery Building Ministry. By that time, we had become

an autonomous organization inside the Academy of Sciences and

had worked with the Ministry for several years. Of course, the

name "Common Machinery Building" was misleading; that

was just for the sake of secrecy. The Ministry was actually focused

on space and its applications, including the launching of piloted

spacecrafts.

As part of the highly developed military complex, this Ministry

had factories, research institutes, test sites and research bureaus

located all over the Soviet Union. To borrow from Solzhenitsyn's

terminology, it was like an "archipelago" of institutions

that worked together to implement a national space program. Naturally,

the headquarters of the Ministry of Common Machinery Building

was located in Moscow.

When we became part of the Ministry in 1985, only a few people

in Azerbaijan knew what kind of work we were carrying out. Our

main scientific direction was remote sensing: studying the Earth's

surface from distant vantage points, usually from satellites

or aircraft. But the field of our activity was quite broad, including

basic research, device building and the development of management

systems and corresponding software. And, of course, the greater

part of our activity was related to the USSR's military programs.

For example, one of our projects was to detect and evaluate the

scale, intensity and other parameters of atomic, biological and

chemical bomb explosions, using satellite surveillance. In the

field of device building, our best-known project was to build

Pulsar-XI, an X-ray spectrometer for the Mir orbital space station.

The spectrometer was designed to look for X-ray sources in outer

space. This device functioned successfully throughout the timespan

of the Mir project.

Flushed with Money Flushed with Money

Since we were dealing with military applications, we were given

as much money as we wanted. If we asked for 100 million rubles,

we could easily get it. The only problem we had was in figuring

out how to spend all that money. It was a situation of "use

it or lose it".

Left: Azerbaijan's National

Aerospace Agency used remote sensing technology to create these

detailed images of the Republic's water resources, soil quality

and land cover.

Let's say we were given 100 million rubles for one year. For

each month, we would have to document that we had spent about

1/10 of that sum. But how could we spend it? Sure, some of it

went for salaries, materials, equipment and orders from our partners.

But that money wasn't considered spent until it was taken out

of the bank account. Very often we had to send telegrams to our

partners in Moscow or other cities in the USSR, asking them to

take the money out of the account as soon as possible. Our reports

had to show that the money had been spent.

When President Reagan started his Star Wars program in the 1980s,

the Soviet Union moved quickly to create a similar program. A

very large factory was on the drawing board to be built in Mingachevir,

in north-central Azerbaijan. This 180,000-square-meter facility

was to be located close to the Kur River, near the railroad and

a large electrical power station. In addition, a small city would

be built nearby to accommodate the factory's workers. At that

time, we didn't even know what kind of factory it would be, perhaps

something related to the Star Wars project. If not that, then

there would have been some other project related to space.

In fact, six such factories

were to be built all around the Soviet Union. They were to be

directed and supervised by a military industrial commission of

the Council of Ministers in Moscow. In fact, six such factories

were to be built all around the Soviet Union. They were to be

directed and supervised by a military industrial commission of

the Council of Ministers in Moscow.

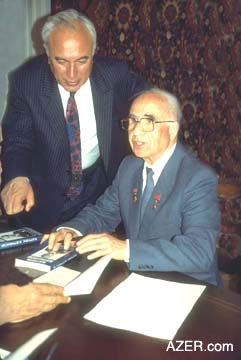

Left: Arif Mehdiyev (standing)

with General Karim Karimov who held one of the highest positions

in the Soviet Space Program.

Ultimately, the project in Azerbaijan never got past the planning

stages. It took so long to carry out the project that by the

time the Soviet Union collapsed, only one percent of the budget

had been spent.

Sudden Collapse

I was Deputy Director of the institute when the General Director,

academician Tofig Ismayilov, died in a helicopter accident along

with many other top officials. Their helicopter was shot down

by Armenians over Nagorno-Karabakh on November 20, 1991. I inherited

the position of General Director. Barely a month later, the Soviet

Union collapsed.

At first, nobody could believe that the news was true. The Soviet

Union had been such a strong state that for many of us it came

as a shock that it could collapse. Many people thought that it

would soon be restored. I remember receiving an order signed

by the Minister that said: "The Ministry has finished its

activity and is liquidated."

Fortunately for us, the collapse of the Soviet Union came at

the end of the year. This meant that all of the funding for that

year had already been received. But the problem was how to fund

the following year: where would I be able to get the money to

pay the salaries a month later, at the end of January?

Since we had been completely financed by the Ministry in Moscow,

it was as if we had been suddenly orphaned.

At that time, the institute had nearly 3,000 employees, many

of them highly qualified specialists and scientists who had studied

at the best universities and research centers in the USSR. I

had to scramble to find sources of money to keep the organization

alive and pay all of those salaries.

There were two real sources of financing. One way was to identify

some contracts using our old ties with the organizations located

in the former Soviet Union. We were successful in signing some

contracts with several of these organizations. But this did not

solve our problem. We understood that this source was not very

reliable and was too weak to enable us to keep our Agency. We

knew we had to find reliable, steady sources of funding, and

that these needed to be from within the country's budget.

But when I visited several high-ranking officials to ask for

money to pay salaries, no one wanted to listen to me. They gave

the excuse that our organization wasn't on their lists. I told

them that from now on, it had to be on that list. They replied,

"We don't know you. You were working with them, so it's

your problem." I had to persuade them that it was their

problem as well, that it was a problem that related to the whole

country. It was important to preserve our scientific and technical

potential.

After considerable effort, I was lucky enough to persuade the

officials that this agency was important to Azerbaijan. The Ministry

of Finance included our agency on their list, and we started

to be funded from the national budget.

By then, a lot of our employees (primarily Russian and Armenian)

had already left because of the war with Armenia. Some of our

Armenian employees went to Russia, some to the States and a few

to Armenia. Actually, one of our former employees is now the

Director of a Remote Sensing Center that is being organized in

Armenia. Many talented Azerbaijani specialists have also left

for various reasons, primarily related to the low salaries.

Difficult Period

Those first two or three years after Azerbaijan gained its independence

were tough for our organization. When we would create a prototype

for a certain device or type of software and offer it to a Ministry

or organization, we were told, "Yes, it's very important

for us. We need it, but we don't have the money to pay for it."

We tried to find partners abroad, but during those early years,

the only partners we knew throughout the world were Russians.

Fortunately for them, and maybe for us, too, just four days after

we created our Aerospace Agency, President Yeltsin issued a decree

on February 25, 1992 about developing a Russian Space Agency.

In the midst of the political and economic chaos that the former

Soviet republics were experiencing, this decision made it possible

to at least identify an entity with whom we could negotiate.

It was actually our first big project after Azerbaijan gained

its independence.

The aim of the project was to develop a method and corresponding

software for recognizing natural objects using space images.

Unfortunately, even though we did the work, we did not get paid

for it. Their situation at that time was even worse than ours.

They could not pay on time, and when you consider the rate of

inflation that was occurring in Russia at the beginning of the

1990s, we received only half of the agreed-upon amount. This

"collaboration" continued until the end of 1994 when

we decided that we would have to be paid before we could continue

to work for them. Part of the money for the work we had completed

in 1994 came two years later, in 1996. By that time, because

of inflation, the ruble had become "thinner" to the

point where it was worth less than one-third of its original

value. The other part of our payment was never received at all.

Eventually, we were forced to become self-sufficient. While we

were still part of the Soviet Union's Ministry of General Machinery

Building, the Ministry told us what to do and gave us the money

to do it. All of a sudden, we were isolated. Nobody was telling

us what to do.

We were faced with a dilemma. If we continued on our present

course, nobody had the money to pay for our projects. So we had

to start from zero and take a different course of action.

I came to the conclusion that first of all, we had to carry out

the types of research and work that Azerbaijan itself needed.

Second, we had to do it by using our own personnel and resources

rather than relying upon outside organizations.

In the past, we had been dependent on other aerospace organizations

located throughout the Soviet Union. In the USSR, each factory

or institute had a main profile of activity. For example, when

we were building the X-ray telescope for Mir, to make the detectors,

we had to buy special material that was produced solely by a

factory in Siberia. All in all, to construct this X-ray telescope,

we had contacts with more than 400 different organizations. As

an official of the Ministry, I was able to visit those factories

and institutions without getting special permission. But when

the Soviet Union collapsed, we no longer had ties with those

organizations. I became a foreigner for them, and they had no

right to discuss any problem with me. Some couldn't even allow

me entrance inside their organizations, despite the fact that

in some cases we had known each other for quite a long time.

After 1995, there was some stabilization - not just in the agency,

but also throughout the Republic, thanks to the efforts of President

Aliyev. Once Azerbaijan's economy began to improve, our organization

was able to find more work. Today, we focus on developing applications

related to remote sensing for various local organizations and

Ministries.

For example, we built a special device for Customs that is used

for detecting radiation. It's held like a pistol and can be used

to identify if someone is trying to bring radioactive materials

across our borders. Other devices have been built for the Committee

of Meteorology, the Committee of Energy and the State Oil Concern.

A New Focus

Most of our activities today are focused on the application of

remote sensing as it relates to certain fields of the economy.

For instance, we just finished a two-year project with the UN

Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) that cost $211,000. Actually,

Azerbaijan was the first country of the Former Soviet Union to

fulfill this kind of project with the FAO.

We purchased about a dozen images from American satellites: 10

pictures from LandSat-5 and several pictures from LandSat-7.

We then used these detailed pictures to work out a GIS (Geographic

Information System) for agriculture in Azerbaijan. The thematic

maps tell us about the country's water resources and soil quality,

region by region.

We also use remote sensing images to learn about ecological problems

like water and air pollution. Unfortunately in Azerbaijan, we

have problems with erosion and salinization of the soil. A lot

of forests have been cut down due to our refugee problem. Using

images from the air, we can show concretely the dynamics of these

environmental problems and then suggest ways in which they can

be resolved.

In terms of natural disasters like mudslides, we are working

to create a model prognosis to help prevent these disasters from

happening. If a mudslide does occur, we provide information and

advice to help people mitigate it.

Remote sensing is also used to locate deposits of oil, gas and

minerals. We have methods that show us where these resources

are likely to be concentrated. This type of work started during

the Soviet period and continues today.

Once the occupied territories [Karabakh and seven surrounding

areas] are freed from Armenian occupation, we'll be able to use

remote sensing devices in airplanes to help locate the estimated

50,000 land mines that are buried in those regions. This will

help speed along the restoration process.

But this is just the beginning. There are many more applications

that we have the potential to implement, once we have the opportunity.

I am optimistic about the future of our agency. First of all,

we have created genuine cooperation among organizations within

the country based on "sell-buy" principles. This has

become possible because of the sustainable improvement of the

economic situation in the country. The future economic situation

seems to be even brighter due to the money that the country expects

to receive from the exploration of the rich oilfields.

In addition, we have established ties with many international

organizations and developed countries. This year we finished

a project for "Strengthening Capacity in Inventory of Land

Cover / Land Use by Remote Sensing," which was financed

by the FAO. As an immediate result of this project, we now have

thematic maps of land cover/land use for the whole country at

a 1:50,000 scale, through the interpretation of satellite data

in accordance with internationally recognized GIS technologies.

For the first time, a digital sample of land cover/land use has

been performed for the whole country, and a unique database has

been generated. I am sure that our collaboration with international

organizations will increase in the future, and our specialists

and scientists will be able to be involved in numerous international

projects.

Now, ten years later, I feel like we're going in the right direction.

Azerbaijan's political stability and the rise in its economy

have helped us a great deal - these are criteria that are fundamental

and critical for scientific work. We have a way to earn money

from our projects and, thereby, hang onto our valuable specialists

and scientists.

Arif Mehdiyev

is General Director of the Azerbaijan National Aerospace Agency

and Vice President of the National Academy of Sciences.

____

From Azerbaijan

International

(9.4) Winter 2001.

© Azerbaijan International 2002. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 9.4 (Winter 2001)

AI Home

| Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| AI Store | Contact us

Other Web sites

created by Azerbaijan International

AZgallery.org | AZERI.org | HAJIBEYOV.com

|