|

Thousands and

thousands of land mines are scattered throughout Azerbaijan's

territory. These unseen threats have already killed many children

and adults and left thousands of other victims maimed and handicapped.

At least 1,400 Azerbaijanis have been killed by land mines from

the war, and 14,670 have been wounded. Two-thirds of these people

are civilians.

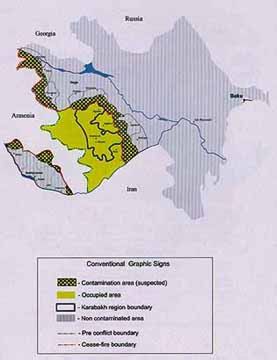

Why doesn't Azerbaijan know where these mines are buried? For one thing, many of the minefields are located on Azerbaijani territory that has changed hands several times between Armenia and Azerbaijan. In addition, some of the mines were buried by volunteer battalions who didn't maintain any records of the locations. ANAMA has the task, through the Azerbaijan National Strategic Plan for Mine Action, issued by the State Commission for Rehabilitation and Reconstruction, to undertake action in a number of areas: management, clearance, survey, Mine Awareness, Mine Victim Support, Information and Public Relations, Training and Human Resource Development. President Heydar Aliyev established ANAMA on July 18, 1998 for the express purpose of clearing mines from the lands that are no longer occupied by enemy forces. ANAMA carries out joint projects between the Azerbaijani government and UNDP. Land mines are designed to kill, period. They remain active for decades and don't distinguish between their victims. Anyone can set off a mine - a soldier or civilian, adult or child. Unfortunately, it's often children who are playing in the area who don't know of the danger (and aren't old enough to read warning signs) and innocently trigger land mines. Sadly, they also are more likely to die from their injuries than adults are. A shepherd grazing his herd of sheep or a farmer working in the field can trigger a land mine and end up losing an arm or a leg, or sometimes become blinded as well. Often, the victim doesn't know that he or she has strayed into a mine area until it is too late.  Above: Many of the veterans from the Nagorno-Karabakh war have amputated limbs, a painful reminder of the consequences of land mines. In every case, it's not just the victim who suffers. An entire family and extended family bear the hardship as well. Often, the person who becomes disabled is the family's primary breadwinner. Families become burdened with the primary care of an invalid. Some of the amputees can be fitted for prosthetics at the Republic rehabilitation centers and the ICRC prosthetic workshop in Baku, Ahmadli and in the 6th Micro-Region. But, in general, there are limited resources for the handicapped in Azerbaijan. For example, it's very difficult to have access to a wheelchair in Azerbaijan, and those who do have them still have to cope with buildings that don't have ramps. Azerbaijan's sidewalks and curbs are also not built to accommodate wheelchairs. Deadly Force According to ANAMA's survey of 21 hospitals and two orthopedic centers in Azerbaijan, as of the summer of 2,000 there had been 1,427 deaths from land mines; 65 percent of those victims were civilians. The survey found that 14,670 Azerbaijanis had been wounded by land mines; again, more than 65 percent of those victims were civilians. Some of the mines that are buried are designed to blow up tanks and require a great deal of weight before they are triggered to explode. But these anti-tank mines may be triggered by something other than a tank. For instance, one man was killed by an anti-tank mine in the Tovuz-Gazakh region because the horse he was riding stepped on it. "People asked me why it happened," Jalalov says, "since I had told them that anti-tank mines were meant to destroy tanks, not people. 'Well', I asked them, 'how much did the horse weigh?' They said about 200-250 kilograms. That plus the person's weight was enough to explode an anti-tank mine." When a person is injured by a mine, the worst thing another person can do is run up to the victim and try to assist. A deminer or other trained person (who may not be accessible in the area at the time) needs to carefully go out to the injured person, checking the ground for nearby mines. "I heard about one soldier who stepped on a mine," Jalalov recalls. "When his friends heard his cries for help, they ran up to him without thinking and triggered other mines. As a result, three soldiers ended up being crippled. From our experience we know that a mine is never buried by itself; there are always other mines clustered near it." There have also been times when a person steps on a mine and then tries to crawl away from the area, only to set off other mines.

Above: Mine-awareness posters teach Azerbaijani children to watch out for dangerous land mines. Mine and Unexploded Ordinance (UXO) Clearance The first mines to be cleared in Azerbaijan are in the regions that are no longer under Armenian occupation. Azerbaijan hopes to regain the other six districts around Karabakh that are currently held by Armenia. If it does, the first major task will be to clear the area of mines before the refugees are invited back in. That will also be a huge, time-consuming and extremely expensive job. In the first stage of clearing mines in Azerbaijan, ANAMA needs to complete an initial survey of where they are located. This work is done by representatives from International Eurasia Press Fund, a national NGO (non-governmental organization) that goes from village to village interviewing local residents to determine where the dangerous areas are. Based on reports of accidents involving people or animals, the group tries to narrow down where the minefields are located. The International Eurasia Press Fund has completed its survey in the Fuzuli region and is now conducting surveys in Aghdam, Tartar, Khanlar and Goranboy. Other regions to be surveyed include Beylagan, Dashkasan, Gazakh, Aghstafa, Tovuz and Gadabay. Once the Fund hears about a minefield that needs to be cleared, they mark it with signs showing that the territory is either "dangerous" or "possibly dangerous". Sometimes the group will mark off the area by putting caution lines around it. For the next step, a mine-clearing group goes in with mine detectors to mark the areas that need to be cleared. These specialists, known as deminers, were trained by Mine Advisory Group from England and received certificates upon completion of their training. A group of 60 Azerbaijanis, some of whom were soldiers in the war, underwent 45 days of training in techniques for clearing mines. "ANAMA received more than 100 applications from local people of Fizuli who wanted to be deminers," Jalalov says. "We chose 45 who were psychologically steady enough to do this job. Once during our training with V. Sadigov, an ANAMA officer, we showed them a film of a mine victim's leg being amputated in the hospital. Some of them walked out: they weren't prepared psychologically for the cruel tragedy and potential hazards of their work." Work as a deminer is very difficult and dangerous, he explains. "They have to move slowly - centimeter by centimeter - across the ground. They wear a special uniform and helmet, which can get very hot and sweaty - plus there's the dust and wind. It's painstaking work, and just one mistake can cost a deminer his life. Thank God, none of our deminers has had an accident. They know that if they do everything just as they've been taught, they'll stay safe. "It's a difficult task, but they understand that this is for all of us. Every deminer knows that what he's doing is important for his country and for the future of his children." Mine-Detection Dogs The deminers are assisted by Mine-Tech, a group from Zimbabwe that brought in dogs that are specially trained for detecting mines. The dogs sniff out the mine components. After an adaptation period, the trainers taught the dogs to identify the explosives that are inside the specific types of mines that were used in Azerbaijan. Azerbaijan will hopefully soon have its own team of specially trained dogs. "A high priority for ANAMA," says Arzu Gasimov, Operating Manager, "is to create a national NGO for Dog Support and Quality Assurance." After the dogs verify the presence of a mine, the deminer returns with a metal detector to determine its exact location. On a good day, depending on the contamination level, a deminer may clear an area of only one to 60 square meters. Once the mine is located and marked, it has to be carefully removed and destroyed. So far, the deminers have cleared land mines in the villages of Shukurbayli and Ashaghi-Kurmahmudlu in the Fuzuli region and an emergency task in the Garachinar village of the Goranboy district. Their work is managed by a national Azerbaijani NGO called Relief Azerbaijan. Public Education ANAMA also works to build community awareness about the grave danger of mines. "We teach people how to live in dangerous places," Jalalov says. "Last year the U.S. State Department gave a grant to UNICEF to help with warning people about land mines. UNICEF put together a project that it could carry out with ANAMA." The educational effort will be carried out first in the areas that carry the greatest risk for mines - regions like Tartar, Barda, Fuzuli, Aghdam, Tovuz, Gazakh and Beylagan. Refugees living in camps near the Armenian border will also be among the first to be trained in how to react when they find a mine or minefield. "We've already trained 15 people to carry out an educational program among 800 teachers," Jalalov says. "They were trained with the help of ANAMA's specialists and UNICEF's international land mine coordinator, Tehnor Dastoor. First of all, people are told how important it is not to touch the mine or enter the mine territory. They should inform officials right away." The teachers are being taught how to treat victims, too. "If a person is injured by a land mine," Jalalov says, "you shouldn't run out to them right away. Try to get help from the officials or deminers, since they know how to reach the victim safely. If that's not possible, the teachers are taught how to approach the person. You have to be careful when you are retracing the footprints. It could take some time to reach the person. One shouldn't sacrifice his own life for the victim's sake. One death is already too many." Another part of the educational campaign includes mine awareness posters for reaching children and adults. "We're going to prepare new posters so that they will be easily understood," Jalalov explains. "Our first goal is to show people what mines and UXOs look like. There will be pictures of mines buried or half-buried as well as pictures of the UXOs that were used during the war. These posters will list phone numbers so that people can contact us when they find a land mine. The roadsides will also have billboards with these messages." ANAMA has chosen to use tools like billboards because it's important to get the message across to everyone. Not all Azerbaijanis who live in the regions have access to television, or even electricity. To make sure that children understand the danger, the organization is putting together short plays to illustrate the message. With the help of Azerbaijan Children's Unity, a group of actors will travel around to various regions to put on educational plays. Continued Threat Land mines will remain a serious problem in Azerbaijan for years to come. Clearing them from the territory is a huge, expensive project. While it only costs an estimated $3 to set a mine, it may cost as much as $1,000 to remove it, especially since no one is sure where they are all located in the first place. ANAMA has $2 million in funding from sources such as the World Bank, UNDP, the United States, Japan and the governments of Azerbaijan and Canada, but it estimates that it will need at least $3.5 million more to cover the costs of materials and equipment, facilities, dog training, mine awareness education and emergency response for mine victims. It also seeks to open a second base camp in Khanlar and add another team of deminers. Ideally, ANAMA would also like to have a mine-clearing machine, which can be used to clear a large amount of territory by remote control. "The machines can withstand great shocks," Jalalov says. "Nothing happens to them, even if they touch a mine, or even an anti-tank mine. After the machine clears the territory, it's much easier for deminers to find the buried mines and clear them. Unfortunately, the machines are very expensive and we don't have the means to get them." Mine-clearing machines typically cost between $150,000 to $1 million, he says. In order to hasten the process, it would be better to use mine-clearance machines in mine/UXO contaminated areas of Azerbaijan. In many areas, long-term development will be all but impossible if the land mines are not cleared out first. Jalalov says: "Our aim is to make Azerbaijan safe from mines so that Azerbaijanis can live there in a safe and secure manner." No matter how soon this happens, these remnants from a bitter war will continue to haunt Azerbaijanis for generations to come. _____ From Azerbaijan International (9.2) Summer 2001. © Azerbaijan International 2001. All rights reserved. Back to Index

AI 9.2 (Summer 2001) |