|

Winter 2000 (8.4)

Pages

40-42

Bridging the Gaps

The Finns

Fascilitate Food Projects

The

idea, in its inception, was quite simple. Due to the collapse

of the Soviet Union and the repercussions that had resulted from

the Karabakh war, some of the members of the Greater Grace Church

in Baku, spearheaded by its pastor, Matti Sirvio, decided to

create a soup kitchen to prepare daily meals for some of the

city's neediest people. It started out on a small scale - a few

dozen people were fed each day, then 50, then sometimes as many

as 100.

As the project developed, its impact began to reach far beyond

Baku to a group of isolated villages in the Ismayilli region,

high up in the Caucasus mountains in north-central Azerbaijan.

In order to supply the soup kitchen with meat and produce, the

church involved the Finnish-Azerbaijani Society and decided to

provide cows and goats to the villagers and help them gear up

for agricultural projects for the following year. As payment,

the families would get to keep a portion of the produce - meat,

milk and cheese - and sustain the soup kitchen in Baku with the

rest.

Above: In cooperation with

the Finnish-Azerbaijan Society and local Azerbaijani villagers,

the Finnish company Aker Rauma Offshore brought in heavy construction

equipment used in the oil service industry to help rebuild a

bridge on the road that leads to Galajig, an isolated mountain

community in the Ismayilli region of the Caucasus mountains.

To the Society's surprise, there was a major hitch in this plan.

The only road into one of the villages crossed over a bridge

that was in a very precarious and dangerous condition. They expected

that it would be a simple job to repair it, but it turned out

to be a major reconstruction that needed cranes and equipment

to be brought in by the oil service company Aker Rauma. In the

end, the village was once again connected to the outside world.

This past September, we asked Ismo Haapala, Finnish Honorary

Consul and Business Development Manager of Aker Rauma, to tell

us how this seemingly small project on the part of Finland grew

to make such a significant contribution to Azerbaijan in two

separate regions of the country.

______

In 1993 and 1994, tens of thousands of Azerbaijani refugees poured

into Baku after fleeing their homes in Karabakh because of the

war with Armenia. Ismo Haapala had been working in Baku for a

few months at that time and remembers the sense of depression

and hopelessness that was in the air.

The elderly were particularly vulnerable, especially those who

didn't have relatives to take care of them. Since their pensions

were negligible, many of them were suffering from hunger.

Left: The newly completed bridge to Galajig,

built by the Finnish-Azerbaijani society, with the help of local

community members and engineers from Aker Rauma Offshore. Now

villagers in Galajig can transport vegetable and milk produce

to Baku all year round. Left: The newly completed bridge to Galajig,

built by the Finnish-Azerbaijani society, with the help of local

community members and engineers from Aker Rauma Offshore. Now

villagers in Galajig can transport vegetable and milk produce

to Baku all year round.

Hannele

Haapala recalls that dismal time in the city's history: "We

started hearing reports that people were coming to hospitals

and dying-not from sickness but from hunger. It was shocking."

A Soup Kitchen

Members of the Greater Grace Church in Baku came up with the

idea to create a soup kitchen. Pastor Matti Sirvio helped to

get it organized. Then the group reached out to Helsinki's Finnish-Azerbaijani

Society to get it involved. Sirvio has since moved to Uzbekistan,

where, in addition to establishing another church ministry, he

has started a similar humanitarian soup kitchen project.

"When we started back in 1995, we rented a small place near

the Nariman Narimanov Metro Station," Hannele says. "The

blind, the poor, the retired came to get their food each day.

Some of them were invalids, so we started taking food directly

to their homes. We named the Kitchen 'Marhamat', which means

'Mercy' in Azeri. Mikayil Ahmadov helped start the project and

continues to be its Director."

The Society does more than just feed the hungry, she explains:

"There are also volunteers who visit homes and help with

other needs, such as cleaning, fixing lights and furniture and

whatever else needs to be done around the house. We want to help

the people who have a very hard life in Baku."

Above

(also bottom):

The Finnish-Azerbaijani Society, members of the local community

and engineers from Aker Rauma Offshore celebrate the completion

of the new bridge to Galajig.

As more and more people began to rely on the soup kitchen, the

Society decided to relocate it closer to Narimanbeyov Square.

Of course, they were running into financial difficulties all

the time. In 1999, the Society decided to seek assistance from

the Finnish government.

Far-Reaching Benefits

Even though this project was designed to help Baku residents,

its effects are being felt in a profound way in the countryside,

too. Now the soup kitchen contracts with five villages in the

Ismayilli region (Galajig, Ivanovka, Hajihatamli, Mujuhaftaran

and Galinchag), which is located about three hours northwest

of Baku.

"We're helping each village get started farming," Ismo

says. "The project owns the animals, and the villagers who

tend them get to keep part of the produce as their salary. This

enables the people to make a living without leaving their own

villages."

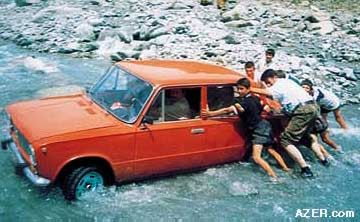

Left: The

old bridge had nearly collapsed and every year during spring

floods when the snows melted off the mountains, the road became

impassable. Left: The

old bridge had nearly collapsed and every year during spring

floods when the snows melted off the mountains, the road became

impassable.

The Society first had in mind to structure the project somewhat

differently. "The original idea was to build a barn for

ten cows and hire people to take care of them," Hannele

recalls. "Then the milk, yogurt and cheese could be brought

to Baku.

"However, when we went to these villages, we saw the extreme

poverty that the people were living in. So instead of building

a barn for ten cows and having two or three people take care

of them, we ended up buying 15 cows and giving each family its

own.

"We now have 15 needy families being supported by these

cows. They had been too poor to be able to afford any livestock.

We bought the best cows so that they would produce lots of milk.

A highly productive cow costs between $200 and $300. Of course,

you can find cows for about $150, but they won't produce much

milk. We wanted each cow to give about 20 liters of milk per

day. This enables the family to live off two-thirds of the produce,

and the other one-third goes to the kitchen."

If the cows produce offspring, a similar formula comes into play.

Hannele believes this encourages the villagers to take good care

of the animals. "They know that having more animals will

increase their standard of living. If they take excellent care

of their single cow, then there's the possibility that it will

someday give birth to a calf. Then that's twice as much income

for the family."

Next year, the Society plans to provide the villagers with some

chickens. They didn't start this year because grain is expensive

for chicken feed, but by next year the villagers will be growing

their own grain.

Some of the villagers are even raising pigs. "We are experimenting

with ten pigs," Hannele explains. "Originally, we didn't

think about offering them, but people asked for them. If the

experiment goes well, we'll add more next year." During

the Soviet period, several districts in Azerbaijan catered to

Russians and Armenians and became famous for their hog-producing

farms despite the fact that Azerbaijan is traditionally a Muslim

country.

Making it Happen

One unexpected obstacle in this supply setup involved Galajig,

a remote mountainous village with a population of about 1,000

people. The only road - an extremely treacherous one - that connected

the village to the rest of Azerbaijan passed over an old, crumbling

concrete bridge. In early spring, when the snows from the Caucasus

melted and brought swollen river waters down through the valleys,

this bridge was usually impassable.

"Had we known at the very beginning that we'd end up having

to rebuild the bridge, we might not have tackled this project,"

admits Ismo. "But since we had already committed to the

villagers, we decided to push forward and include the bridge

repair as part of the project. We thought we could use the old

structure and do some repairs, but we ended up rebuilding the

entire bridge.

"When we investigated, we discovered that the foundation

of the bridge had been mostly washed away over the years because

of the rising waters. The concrete slabs were just propped up

on the gravel in the riverbed. There was nothing to secure them

and very little steel in the concrete slabs to reinforce them,"

he observes.

Finnish company Aker Rauma, which is involved in construction

as it relates to oil service projects, lent support by bringing

in the necessary cranes, generators and tools.

"Our Finnish engineers came up with the basic idea of how

to design the bridge," Ismo says, "but it was the local

people - 100 percent - who carried out the physical work. It

was very much a joint project."

The reconstruction took 17 days during late July and early August

of this year, when the river bed was at its lowest. "It's

probably the best-built bridge in all of Azerbaijan," he

says.

The bridge was constructed to be one meter higher than the original

bridge so that water can no longer wash over it as it has in

past years. The village is no longer cut off from the rest of

the country during the rainy season. Galajig is now producing

goats, potatoes and onions.

Flour Mill

Another obstacle turned up in the villages selected for growing

wheat. The problem was that there was no flour mill in these

villages, and the people were paying too much to transport their

wheat to the nearest mill. Once again, the Society came up with

a workable solution.

"We bought a second-hand mill in Finland and received another

one as a gift from a private donor," Ismo explains. "The

mills have the capacity to grind about 1.5 tons of flour a day.

We're waiting for the next major oil service shipment from Finland

to bring the mills here, as they can be brought in free of charge

as humanitarian cargo. Once we take them and set them up in the

villages, the people there will pay the same amount as they would

at other mills, but they'll save all their transportation costs.

Again, a portion of the money for grinding the flour will go

to support the soup kitchen. This is another way that we can

help the people in the village and support the soup kitchen at

the same time."

Food for the Future

Once the project is completely in place, the organizers hope

that it will be self-sustaining. "It should maintain itself,"

Ismo insists. "Once you've set this project up, you don't

need to pump it up with money all the time. After the first few

years, the villages will produce enough to support themselves

as well as the kitchen, year after year." They've added

a four-wheel-drive vehicle to the project to facilitate transporting

the produce to and from Baku.

This long-term perspective fits the Society's strategy of working

side by side with the Azerbaijani people to ensure that their

needs are met. "We didn't want to help in the usual way

- buying a container full of things, dumping it in the middle

of a village and then just disappearing," Ismo says. "Enabling

Azerbaijanis to care for themselves is a goal that is definitely

within reach. We're using everything we know about this country

and this region to make things happen."

____

From Azerbaijan

International

(8.4) Winter 2000.

© Azerbaijan International 2000. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 8.4 (Winter 2000)

AI Home

| Magazine Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|