|

Spring

1999 (7.1)

Pages

65-69

Quest for

Freedom

(1960-1991)

Profile

of a Dissident

Bakhtiyar Vahabzade

(1925-February

13, 2009)

by

Jean Patterson

AI

7.1 Special Feature Articles

Late one night

in 1952, Azerbaijani poet Bakhtiyar Vahabzade lay wide awake

in bed.

He couldn't stop thinking about the conversation he had had earlier

that day with a close friend, composer Gambar Huseinli. They

were both critical of the Soviet government, but at the same

time suspicious of each other and afraid to talk about it openly.

Huseinli had already been arrested once before, allegedly for

referring to Stalin as a "dictator" in a private conversation.

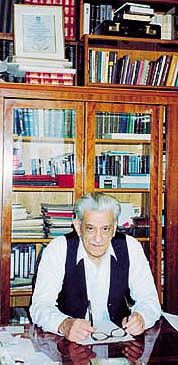

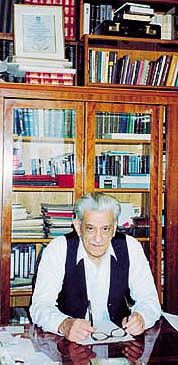

Right: Bakhtiyar Vahabzade

in 1969

Earlier that day, Vahabzade had asked Huseinli why he had been

arrested. Huseinli had exploded in anger, cursing Stalin and

complaining about how badly he had been mistreated. He regretted

his words at once, and suddenly halted his tirade. Trying to

console him, Vahabzade admitted that he agreed with him about

Stalin, that the man was a cruel dictator who had killed thousands

of innocent people.

Later that night, a sleepless Vahabzade worried about having

been so honest about his own beliefs. Huseinli had just been

released from prison. Was he a spy for the KGB? He had heard

that political prisoners were often recruited as such. Would his friend turn him in? Paralyzed

by fear, Vahabzade decided to go to Huseinli's house first thing

in the morning and beg not to be betrayed. his friend turn him in? Paralyzed

by fear, Vahabzade decided to go to Huseinli's house first thing

in the morning and beg not to be betrayed.

That night, shortly after 1 a.m., Vahabzade heard a car stop

outside his house. During the repressive Stalin era, political

prisoners (including poets who refused to conform to Soviet ideals)

were usually arrested at night. Cars called "black ravens"

would pull up around 2 a.m. There would be the sound of footsteps,

a knock at the door, then people would be whisked away, never

to be seen again. Was it his turn? Vahabzade panicked, got up

and burned anything that he thought could be used as evidence

against him - namely the anti - Soviet poems he had written over

the previous decade but had shown to no one. A few poems he decided

not to destroy. He hid them inside his mother's artificial leg.

Left: Sketch by Gunduz

It turned out that the car was not a police car and had come

for someone else. Early the next morning, as he was getting ready

to go visit Huseinli, there was a pounding on his door. Outside

was a terrified Huseinli, who also had not slept all night. He

begged Vahabzade not to turn him in. They both took back their

words from the day before, repeating to each other, "Stalin

is our father, he is our leader."

Vahabzade later wrote about this experience in his poem "Two

Fears" (Iki Gorku) (1988) which he published on the eve

of the collapse of the Soviet Union. He vividly evokes the Stalin-era

atmosphere of suspicion and distrust of even closest friends.

Two Fears

(1988)

(Dedicated

to the memory of our deceased composer Gambar Huseinli)

He was a friend

of mine, Composer Gambar,1

Whose songs ever smelled of the native land.

The sweet songs we two had once composed

Were passed from mouth to mouth.

He had never

told me, but I knew that

He had been arrested some years before.

But I did not know what his fault was.

I never asked him, nor did he tell.

Once Gambar

was complaining to me

about his life,

I felt heaviness of heart...

I asked him:

But why did they arrest you?

Suddenly he exploded like a bomb:

Don't you know why?

Because I had cursed the world.

I had called "The Father of the Nations," 2

enemy.

Then he became

frightened of what he had said,

And suddenly stopped, not breathing a word.

Evidently, he was afraid of me,

Thinking I might be a spy.

"Sorry,

I got excited," he said suddenly,

"Sometimes I don't know what I'm doing."

I felt the humility in Gambar's voice,

But in a way he was right to be suspicious.

I supported

everything that he said

In order to dispel his doubts...

After arriving home from Gambar's place

I started thinking,

Fear and agitation gave me no peace.

I remembered our talk...

I said to myself,

you fool,

Why did you get yourself into trouble?

Why did you confirm his words after all?

How do you know that Gambar was not saying

Those words against that despot deliberately?

When thousands of innocent people

have been executed,

And thousands exiled,

Will they set someone free

Who has called the government leader "enemy"?

Where was the logic in this, after all?

I couldn't believe his curses were honest.

What if he were complaining deliberately

about his life, about the times,

What if he were trying to get my opinion.

And what did I do? Me, fool that I am,

told him what I thought.

That night I

couldn't sleep,

With thoughts I fought...

What thoughts did I have:

When they come to imprison me,

They will search my archives,

And then my writings, dear me.

I thought what

I had, white or black!

Like a stranger I looked inside myself,

Then got out of bed at midnight,

And began scrutinizing my poems.

Like an inspector,

I looked at the poems

still unpublished

And a shudder came over me.

"If they find these," I said to myself,

"That despot will kill me,"

Maybe to burn

them? What else could I do?

After all, who is indifferent to the life he leads?..

Such trouble to burn the poems

That demand truth and justice from this world!

I have to sacrifice my thoughts and feelings

Just to live out the rest of my life!

My body became

cold, my heart trembled

With the fire and flame of the burning poems.

But I spared some of them

Saying, "It is enough,"

Saying, "That'll do."

I spared some

of my poems that day,

Crumpled papers still remain.

I hid them for the future,

I hid them in my mother's artificial leg.

I turned over

my thoughts and judgments

page by page:

"As soon as the dawn breaks

I'll go to him.

I'll ask him not to betray me,

I'll tell him I was lying yesterday,

'Let's keep it between ourselves.

I was agreeing just to support what you had said.

In fact, I love that genius leader very much.

He has bestowed these happy days upon us.

He is our only support in this world,

He is our thinking brain, our seeing eye.'"

"What a

mistake I've made,"

Thinking so till morning, I blamed myself.

As soon as the dawn broke, I got up and dressed.

At the same time, someone began knocking

at the door...

Who might it be so early in the morning?

I stood before the mirror

My body trembling.

I had no strength even to open the door.

"He must have already betrayed me last night.

They're coming to arrest me, where shall I flee?"

And knocks continued-

Knock, knock and knock.

The knocking wouldn't cease

Without achieving its aim...

"Who's there?"

"It's me, brother."

It was Gambar's voice.

That was enough for me.

Perhaps he had come as a witness,

Or come to make me be silent.

I opened the

door with trembling hands,

He fell on my neck and embraced me,

And began crying bitterly.

He cast a sorrowful glance

To the left, then to the right.

Began hastily interpreting

The talk we had had a day before.

"I was just joking yesterday;

In truth, I love that genius leader.

He is our only support in this world.

He is our thinking brain, our seeing eye."

I understood

him,

But kept silent... Realizing the falsehood

Of all those interpretations.

Time had made hypocrites of us all,

Making us deny all we had said a day after our talk,

It turned out he also had not slept that night.

Footnotes:

1 Gambar

Huseinli is perhaps most fondly remembered for his children's

song, "Jujalarim"

- My Little Chicks [See

AI 5.4, Winter 1997]. Sound Sample: www.azer.com. Up

2

The

father of the nations - meaning Stalin. Up

Can

the country that has such guns be afraid of anything?

But you are afraid of everything even today

And yesterday, you were afraid.

One bright mind, One worrying heart

Are more frightening to you than thousands of H-bombs!

(Words

directed at the U.S. but intended for the USSR) - Bakhtiyar Vahabzade

Much of Vahabzade's

poetry did criticize the Soviet system. Sometimes, he kept those

poems private. Some of the others that he managed to get published

incorporated clever strategies to circumvent Soviet censors.

Early Struggles

Vahabzade's resistance

to the Soviet government began during his early Vahabzade's resistance

to the Soviet government began during his early  childhood

in Shaki, a mountain town in northwestern Azerbaijan. In 1930,

there was an uprising there against the Soviet government's collectivization

policy. Vahabzade, who was five years old at the time, remembers

clearly how the Soviet army sent from Baku cruelly suppressed

the protesters. Thousands of people were jailed; some were shot,

others fled into the mountains and lived as outlaws. The government

continued their pursuit of them for more than a decade. childhood

in Shaki, a mountain town in northwestern Azerbaijan. In 1930,

there was an uprising there against the Soviet government's collectivization

policy. Vahabzade, who was five years old at the time, remembers

clearly how the Soviet army sent from Baku cruelly suppressed

the protesters. Thousands of people were jailed; some were shot,

others fled into the mountains and lived as outlaws. The government

continued their pursuit of them for more than a decade.

Vahabzade's family had a deep hatred of the newly installed Soviet

government. Several close relatives had died in the uprising.

"Outlawed Abbas," famous for his bravery and fearlessness

among the people, was captured and killed. It was the first corpse

Vahabzade had ever seen in his life. He remembered, "I saw

how my grandfather sitting in front of the window cried bitterly

over his death, and how my grandmother, wearing a black silk

scarf over her head, was wailing the loss."

In 1933, Vahabzade's father and uncles were arrested for helping

the outlaws but were released when a relative in the police force

intervened. To escape further danger, the family fled Shaki for

Baku.

Left:

Bakhtiyar

Vahabzade in his study, 1992.

Growing up witnessing these violent events, Vahabzade became

more and more indignant against Soviet authority. While in high

school in Baku, he started channeling his anger into poems, describing

feelings that could not be expressed publicly.

In the meantime, he pursued a career as a poet and professor.

In 1942, Vahabzade was admitted to Azerbaijan State University

to study philology and later became a professor there. In 1945,

he was accepted as a member of the Soviet Union's Writers' Union.

If, in

your mother tongue, you cannot say

"I am free, I am independent."

Who can believe that you really are?

- Bakhtiyar

Vahabzade

Defending the use of

Azeri

One

thing about Soviet Azerbaijan that particularly upset Vahabzade

was that his native Azeri tongue was being systematically replaced

by Russian. In one poem he wrote, "Once it would flow fluently/

But today it is frozen./ My mother tongue is so miserable today/

As if it has been trampled."

In his poem "Mother Tongue" (1954), he vents his frustration

at the substitution of Russian for his mother tongue. Naturally,

it was difficult for him to get the poem published. When the

famous Azerbaijani poet Samad Vurgun heard about the poem from

his son Yusif, he told Vahabzade that he would help him publish

it. As Vurgun and Vahabzade sat n his study, reviewing the poem,

Vurgun suggested that he add an epitaph from Lenin to serve as

a "shield". It read, "We love our mother tongue

and our country." Since the words could be directly attributed

to Lenin, no one could accuse Vahabzade of being nationalistic.

The poem was published a few days later.

This kind of technique soon became a characteristic feature in

Vahabzade's work. In order to outwit the censors, he masked his

true intent by transferring Azerbaijan's problems to a different

time period or a different geographical setting. In this way,

he could address contemporary issues by simply displacing them

from the context of Soviet rule.

For instance, "The Roads, The Boys" (Yollar Ogullar)

(1964) is a poem about the national liberation movement in Algeria.

Vahabzade realized that the Algerians' struggle also epitomized

Azerbaijan's struggle against the Soviet government. But he succeeded

in getting the poem published. A friend informed the KGB, accusing

Vahabzade of criticizing Russia. It was Mehdi Husein [see Underground

Rivers Flow into the Sea], then secretary of Azerbaijan's Writers'

Union, who vouched for Vahabzade, insisting that the poem was

not anti-Soviet.

In the 1970s, Vahabzade decided to write a poem about Andrei

Sakharov, the famous Russian physicist who was being threatened

for his anti-Soviet opinions. Vahabzade wanted to write about

the scientist's brave protests, but dared not. Instead, he concentrated

on Linus Pauling, who had been blacklisted in the U.S. He knew

his readers would recognize that he was actually alluding to

Sakharov and the USSR, not Pauling and the U.S.

Dawn

(1972)

American chemist

Linus Pauling (1901-1994), the focus of Vahabzade's poem "Dawn,"

was awarded the International Lenin Prize (1970) "For Consolidating

Peace Among Nations" and the distinguished honor of two

Nobel Prizes, one for Chemistry (1954) for his work on chemical

bonds. His second, the Nobel Peace Prize (1962), was awarded

for his efforts on behalf of the nuclear test ban treaty that

was signed in 1963.

During the 1950s, Pauling became a victim of the McCarthy-era

"witchhunts" in the U.S. His passport was withdrawn

by the State Department because his "anti-Communist statements

were not strong enough." In fact, this travel restriction

almost prevented him from going to his own Nobel award ceremony.

Pauling was targeted because he spoke out repeatedly against

official U.S. government policies during his campaign for peace,

disarmament and the end of nuclear testing.

(Addressing the U.S. government)

You have your own position

In the line-up of governments.

You have atomic and H-bombs,

You have tanks and cannons,

You have these weapons,

You have those weapons!

Can the country

that has such guns

be afraid of anything?

But you are afraid of everything even today

and yesterday, you were afraid.

One bright mind,

One worrying heart

Are more frightening to you

Than thousands of H-bombs!

You were never

afraid of atomic bombs

As much as you are afraid of such thoughts

of such minds!

Why did you become afraid of one mind

Which was able to separate colored lies

from the truth,

To distinguish truth from abomination?

-I know why!

If Linus is a slanderer, if he is a liar,

Then why do you hold back what he has said

from the people?

And why are you arresting him?

(Addressing

courageous ones like Linus Pauling)

You who suffer because of the Motherland,

You who don't keep silent but ever speak,

You were destined for death and jails!

(Again addressing

the U.S. government)

You have atomic bombs; you have missiles,

In spite of all these weapons, you are afraid.

The heaviness of this fear

Is the weight and price

Of the harm you have done.

Look at that scarlet horizon,

It is dawn,

It is dawn!

Despite this

literary sleight of hand, Vahabzade's readers read between the

lines and understood what he was saying. He even believes that

some of the censors understood, but let the poem slip through

if they could do so without being caught.

Photo: A plaque in the Writer's Union gives

tribute to 25 writers who were killed during the repressive years

of Stalin. The names include: Photo: A plaque in the Writer's Union gives

tribute to 25 writers who were killed during the repressive years

of Stalin. The names include:

Amin Abid, Kazim Alakbarli, Yusif Vazir Chamanzaminli, Bakir

Chobanzade, Sultan Majid Ganizade, Gantamir, Mustafa Guliyev,

Seyid Husein, Ahmad Javad, Husein Javid, Ismayil Katib, Vali

Khuluflu, Salman Mumtaz, Atababa Musakhanli, Mikayil Mushfig,

Alabbas Muznib, Hajibaba Nazarli, Ali Nazmi, Omar Faig Nemanzade,

Aghahusein Rasulzade, Ali Razi, Haji Karim Sanili, Taghi Shahbazi

Simurg, Boyukagha Talibli and Hanafi Zeynalli.

The most

famous of these writers are featured in this issue: Ahmad Javad

(27), Husein Javid (20) and Mikayil Mushfig (26).

A Close Call

Some

poems did not manage to "slip through". For example,

Vahabzade narrowly escaped serious trouble for writing "Baku"

(1956). In this poem about 18th-century Azerbaijan, Vahabzade

describes the fortress walls that surround old Baku but actually

refers to Soviet Azerbaijan:

Those stones

piled up like teeth,

The honor of our ancestors is valuable for us.

Those white stone teeth showing

Are clenched

Showing the hatred towards foreign enemies.

A well-known poet turned him in for this poem, saying that it

was "anti-Soviet." The poet wrote a letter to the secretary

of the Writer's Union, Ali Valiyev. Fortunately, Valiyev was

looking out for Vahabzade, the friend of his son. Valiyev dictated

a statement to help him clear his name. It read: "While

saying 'foreign enemies,' I haven't meant the present time but

the times when the fortress walls were built. Because these fortress

walls surrounding Baku were constructed with the purpose of defending

Baku from the foreign enemies in those days." Valiyev showed

the statement to the informant and told him to put an end to

the matter.

Getting Caught

Vahabzade was not always able to dodge his censors and detractors.

One of his poems even cost him his job. In "Gulustan"

(1959), Vahabzade objects to the division of Azerbaijan into

two parts by the Gulustan Treaty of 1813. This treaty between

Russia and Iran assigned "Northern Azerbaijan" (the

modern-day Republic of Azerbaijan) to Russia, and the other part

which is commonly referred to as "Southern Azerbaijan"

to Iran. Vahabzade's poem was too controversial to be published

in the mainstream press, but he managed to get it printed in

"Shaki's Worker" (Nukha Fahlasi), a newspaper in his

hometown. Word of the poem soon spread throughout Azerbaijan.

When the Central Committee found out about it in 1962, Vahabzade

was fired from his job as a university professor and branded

as a "nationalist".

Vahabzade also got into trouble for questioning the Soviet Union's

suppression of the Azeri language. During the Soviet period,

the Azeri language, like the national languages of other Republics,

was systematically replaced with Russian, which became the official

language of all government dealings.

As more and more parents sent their children to Russian-language

schools, the number of Azeri-language schools decreased. Sometimes,

the children who were taught in Russian could barely speak Azeri.

Vahabzade sent his own children to Azeri-language schools and

often argued with parents who did otherwise. When he found out

that his son's literature teacher was sending his own children

to Russian-language schools, he angrily confronted him and questioned

his logic. (Without Azeri-language schools, the teacher would

have been out of a job.) The next day, Vahabzade wrote a poem

about the incident entitled "Hypocritical".

Vahabzade believes the existence of any nation is first of all

connected with its language. As he puts it, "'No language'

means 'no nation.'" Throughout his career, he has repeatedly

mourned the suppression of Azerbaijan's mother tongue.

The most prominent expression of this outrage is in his poem

"Latin" (Latin Dili). In 1967, Vahabzade visited Casablanca

and found a similar case: the indigenous language was dying out

there because it was no longer the official language. In his

poem, he writes that the Latin language is not really a "dead"

language-it is used today throughout the world by doctors and

academics. The original nation no longer exists, but the language

does. On the other hand, a contemporary nation that no longer

uses its mother tongue does not fully exist. He writes:

If, in your

mother tongue, you cannot say

"I am free, I am independent."

Who can believe that you really are?

Line of Defense Line of Defense

To cover himself, Vahabzade wrote "Casablanca" at the

bottom of the poem to detract from its intended geographic context.

The KGB was suspicious, but even after questioning Vahabzade,

they couldn't prove that the poem was actually about Azerbaijan.

Vahabzade defended himself by maintaining that the poem was about

the Arabic language,  not

Azeri. not

Azeri.

Photo:

Poet Bakhtiyar

Vahabzade (right) meeting with Suleyman Demirel, President of

Turkey (1995).

In private, he wrote a poem about the experience,

"In the Mourning of Others," describing himself:

"Assigning my people's troubles to others,

I wept for my loss through their mourning."

After writing "Latin", Vahabzade was called into a

meeting with Jafar Jafarov, a scientist-critic who worked as

an ideological secretary of the Central Committee. One of Vahabzade's

friends, Teymur Elchin, was also there. When Vahabzade defended

himself by saying that his poem was about the Arabians, Jafarov

exploded: "Do you think we're idiots? We know perfectly

well what you're talking about. You've been reprimanded before-when

will you learn your lesson?" He threatened to have Vahabzade

fired from his job.

Vahabzade still insisted that the poem was about what he had

seen in Casablanca. Elchin laughed at his words and said to Jafarov,

"I think he sees his mistake. In the future he will be more

careful." A few days later, Vahabzade learned from Elchin

that Jafarov had been directed by the KGB to try to "cultivate"

him. After that, it was much more difficult for Vahabzade to

push his poems past the censors.

Today, Bakhtiyar Vahabzade's situation is quite different. He

is known as the "People's Poet of Azerbaijan" and is

an independent member of Parliament. Some of his more controversial

works have been published for the first time in volumes such

as "Fairy-Tale Life" (1991) and "The Bridge Has

Come Far From the River" (1996). An English-language collection

of his poems and short stories, "Selected Works of Bakhtiyar

Vahabzada," was recently published by Indiana University

Turkish Studies Publications. The New York Times even featured

him in a Octo-ber 9, 1997 article by Stephen Kinzer entitled,

"In Azerbaijan, Poets Tear Down the Fences."

Fairy-Tale Life

(1964)

Though you are my own mother,

I am so upset with you, mom...

You taught me to feel and to think,

But I wish I had been deprived

of feeling and thinking.

You taught your baby to see, to speak,

But I wish I had been born deaf-mute

to this world.

Taking me by

the hand you taught me to walk,

I went round mountains, round lowlands.

Instead of teaching your baby to walk and to run,

You should have taught him how not to fall...

Thoughts flow over me layer by layer,

Answers too venturesome, questions forbidden.

Life is strange to those who know it,

But so familiar to those who don't know.

Where are you?

My only mom, where are you?

Come! I want to put my head upon your lap again.

Tell me tales again, let the time stop,

Let me see how heroes in those tales

Conquer double-headed ogres,

And how they escape from wizards.

Tell me, where is peace?

Why won't it come to our lands?

Don't tell me

anything, don't, mom, keep silent.

I can't understand the legends you tell.

I've seen such real giants in the world

Ogres from those tales are like chicks in comparison.

I've seen such ignorant and stupid persons

Who call hills, slopes and slopes, hills,

just to please others.

I've seen such foxes that call

The steel chains on their arms, bracelets.

I've seen bandits

relaxing

After ransacking their own countries.

I've seen merchants who have sold

Their Motherland not for jewels

But for simple applause, "Good for you's."

I've seen old

women, atheist, godless,

Who call roses, thorns and thorns, roses.

I've seen leaders, brutal, merciless,

Cursing their fathers, bowing down to others.

Since the time

I have felt this world and known it,

Life has fallen into disgrace for me.

The horrible things that appear in fairy-tales,

I have seen in real life in this world, mom.

Mazahir Panahov

contributed to this article and Aynur Hajiyeva translated the

poetry.

From

Azerbaijan

International

(7.1) Spring 1999.

© Azerbaijan International 1999. All rights reserved.

Back to Index

AI 7.1 (Spring 99)

AI Home

| Magazine

Choice | Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|

his friend turn him in? Paralyzed

by fear, Vahabzade decided to go to Huseinli's house first thing

in the morning and beg not to be betrayed.

his friend turn him in? Paralyzed

by fear, Vahabzade decided to go to Huseinli's house first thing

in the morning and beg not to be betrayed.

Photo: A plaque in the Writer's Union gives

tribute to 25 writers who were killed during the repressive years

of Stalin. The names include:

Photo: A plaque in the Writer's Union gives

tribute to 25 writers who were killed during the repressive years

of Stalin. The names include: