|

Winter 1997 (5.4)

Pages

72-75

The Emergence

of Jazz in Azerbaijan

Vagif

Mustafazade: Fusing Jazz with Mugam

by Vagif

Samadoglu

Music samples

Related articles

1 All

Eyes on Aziza - Catching up with Azerbaijan's Famous Jazz Artist

- Aziza with Betty Blair

2 Aziza Mustafa

Zadeh - Jazz, Mugam and Other Essentials of My Life - Aziza

Mustafa Zadeh with Betty Blair

Before

the turn of the 19th century, Baku was already known for its

oil. Europeans gravitated to this city on the shores of the Caspian,

and together with local entrepreneurs, they succeeded in producing

more than 51 percent of the world's supply of oil. Before

the turn of the 19th century, Baku was already known for its

oil. Europeans gravitated to this city on the shores of the Caspian,

and together with local entrepreneurs, they succeeded in producing

more than 51 percent of the world's supply of oil.

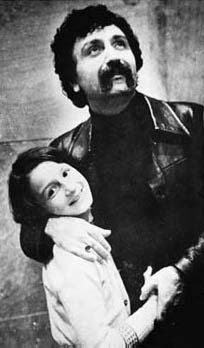

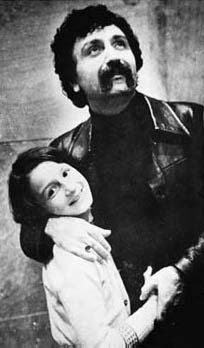

Left: Aziza

and

her father, Vagif Mustafazade

At about the same time, America was giving birth to a new musical

form-jazz. This mesmerizing new sound which originated in the

restaurants and back alleys of New Orleans and Chicago drew upon

many different cultural traditions, including African rhythms,

Asian improvisations and abstract thinking, European classical

music and even symbols borrowed from Native American tribes.

Soon afterwards,

this new musical synthesis found its way to other cities all

over the world, including Baku. Newspaper archives indicate that

bands were performing jazz in Baku restaurants. It's very possible

that Robert Nobel and his brothers, Ludwig and Alfred, listened

to jazz in Baku. Unfortunately, there are no early recordings

to determine the professional quality of these performances.

But an ironic twist of fate brought this economic boom to an

abrupt stop. In 1920, the Soviet regime gained control of the

region, and soon Soviet doctrine profoundly affected all aspects

of life-even attitudes toward art, literature and emotions. Everything

was subject to Communist ideology and central control. Nothing

escaped its scrutiny, not even music - including what to sing,

what to play and what to listen to. These decisions were all

made in the Kremlin in Moscow - not by local artists.

Soviet Ban On Jazz

But

in 1945 at the end of what the Soviets call the "Great Patriotic

War" (World War II), Stalin decided to prohibit jazz throughout

the Soviet Union, by labeling it "music of the capitalists."

Jazz had already been banned by Hitler in Germany in 1933 on

the grounds that it was "the music of blacks." But

in 1945 at the end of what the Soviets call the "Great Patriotic

War" (World War II), Stalin decided to prohibit jazz throughout

the Soviet Union, by labeling it "music of the capitalists."

Jazz had already been banned by Hitler in Germany in 1933 on

the grounds that it was "the music of blacks."

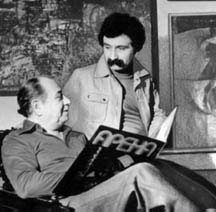

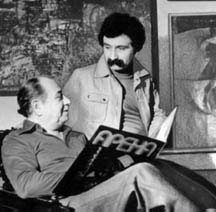

Left: Two of Azerbaijan's

great jazz pianists - Tofig Guliyev (seated) with Vagif Mustafazade.

Consequently, between 1945 and Stalin's death in 1953, not only

jazz, but even music played on the saxophone was prohibited.

It's a fact that during that period, the saxophone solo in Ravel's

famous "Bolero" was played on bassoon.

Such a ban could have been expected. Totalitarian regimes always

seem to be suspicious of artistic forms that are based on egalitarian

improvisation. Even today, jazz is usually not sanctioned in

countries ruled by dictatorial regimes.

Despite these prohibitions, by the 1950s, a new jazz movement

began to emerge in Azerbaijan which came to be known as "jazz

mugam" or "mugam jazz" (whichever term you prefer).

Its origins were in Baku; its brain child, Vagif Mustafazade.

Childhood Friendship

Vagif

was born in 1940 in a difficult period when our country did not

wear the smile of jazz on its face. But he went on to become

a shining star in the darkness and developed into an extraordinarily

great jazzman, pianist and composer.

Actually, I

can't quite remember the first time I met Vagif. It seems I've

always known him. It must have been in my early years at school.

He was a year younger than me. Later I discovered that his name,

as well as mine, had been chosen by my father, Samad Vurgun,

the renowned poet. His mother had asked my father to suggest

the name. "Vagif" is an Arabic word that means "extremely

knowledgeable."

The

truth is that Vagif Mustafazade, himself, could have become a

poet. Not many people knew his verbal acuity. My family is fond

of reminiscing about the time when Vagif was only three years

old and recited from memory a section from my father's play,

"Farhad and Shirin." He had only heard the work once. The

truth is that Vagif Mustafazade, himself, could have become a

poet. Not many people knew his verbal acuity. My family is fond

of reminiscing about the time when Vagif was only three years

old and recited from memory a section from my father's play,

"Farhad and Shirin." He had only heard the work once.

Left:

Lala Mustafazade, classical

pianist.

I well remember the days when Vagif and I used to gather with

friends near Maiden's Tower or in Sabir Park and recite "meykhana"

(pronounced MEY-kha-na). "Meykhana" is a kind of rhythmic

poetry, somewhat like contemporary "rap" in the West.

It's a pity that none of those pieces were ever recorded. As

might have been expected, "meykhanas" were also prohibited

in Soviet Azerbaijan, simply because improvised forms of poetry

could not be controlled and censored. They were considered too

volatile. The totalitarian regime branded it as "hooligan

poetry." Well, it seems Vagif and I were among the "great

hooligans."

Listening Secretly

- BBC

Vagif

lived on a second-floor apartment in Ichari Shahar (the Inner

City), which has since been converted into the Vagif Mustafazade

Home Museum and can be visited today. The building was constructed

during the oil boom, but after the Soviets came, this place,

like hundreds of others, was savagely divided into small apartments.

The Mustafazades-Vagif and his mom, Ziver Khanum (Mrs. Ziver)-were

assigned one small room which served as both bedroom and living

room. Fortunately, it was bright and bathed in sunlight. They

shared a kitchen and bathroom with other occupants in the building.

Despite the impoverished setting, that single one-room apartment

became a repository of an immense musical knowledge and in shaping

the movement of jazz in Azerbaijan. I have so many fond memories

of times spent together there, including the endless hours we

used to listen secretly to the short wave radio programs of BBC

just to catch some of the jazz they broadcast. Neither of us

knew English.

Afterwards, we would try to reproduce the music that we had heard

on the old piano in the apartment. Radio BBC was our only exposure

to jazz at the time. Despite the fact that I had studied music

my entire life, it wasn't until the mid-1950s that I first laid

eyes on a jazz score. The only thing we could do was to listen

at every chance we got, and then try to imitate the sounds that

we heard. We didn't have access to personal tape recorders in

those days. Vagif was especially adept. He had an incredible

ear for music.

For example, once his piano teacher asked him to learn Rachmaninoff's

"Prelude in C-Sharp Minor." But he didn't have access

to the score, so he listened to the record several times and

that's how he learned to perform it.

On occasion, we would hear jazz excerpts at the movies. You could

always tell whenever an American spy was about to appear in a

scene in a Soviet movie. His entrance was signaled by jazz. After

World War II, we had access to a few American movies. Some had

jazz on their soundtracks.

Vagif and I used to watch these films at the cinema over and

over again, sometimes 20-30 times. We would wait for the sections

that had jazz, then rush back home to try to reproduce them while

they were still fresh in our minds. I remember that "Sad

Baby," a song in the film, "The Fate of an American

Soldier," always used to make us cry.

No Longer Outlawed

After

Stalin's death in 1953, the prohibition against jazz was gradually

lifted. Still, the public was highly suspicious. As could have

been expected, the situation didn't change overnight. For example

in 1957, Vagif was scheduled to give a concert at Music School

#1, where his mother taught piano. His program included two or

three short jazz compositions. But the concert was never allowed

to take place because the music was branded as "capitalist."

Therefore, Vagif and other musicians involved with jazz, mainly

performed in clubs and each others' homes. Classical jazz, including

dance music and "blues," formed the basis of Vagif's

repertoire. Early on, he created some magnificent renditions

of the Fox Trot, the Charleston and the One-Step, as well as

some memorable pieces from Glenn Miller's "Serenade of the

Sunny Valley."

After that, B-Bop came along. However, Vagif always had an affinity

for improvisational jazz. He didn't really understand why, but

he began living with this love and obsession. It was a mystery

to him why he was so attracted to it.

In 1958, he was selected as pianist for the Folk Instruments

Orchestra, and they performed several concerts at the Philharmonic

together. He continued to play dance jazz in clubs, but it was

clear that he was not comfortable. He was in search of something

else. He was unsettled and this quest tortured him morally, sometimes,

even physically. The fact that he couldn't expose his inner world

openly to his audience and that he was deprived of sharing his

feelings with people freelygnawed at him. That's when he started

drinking and getting involved with drugs.

The words of his critics didn't help any either. Their opinions

often contradicted one other. Sometimes they praised him; other

times, they brutally criticized him.

Jazz Mugam is Born

Eventually,

Vagif created a new sound-his own kind of jazz-a fusion of jazz

with a form of music indigenous to Azerbaijan-the mugam. Essentially,

Vagif Mustafazade's jazz was the first to be built upon the native

music of the East. Such a trend was not new. Azerbaijan was used

to being "first" when it came to music in the Muslim

East. For example, Azerbaijan lays claim to the first opera,

the first female opera singer, the first ballet and the first

symphony orchestra.

Mugam jazz is jazz based on the modal forms or scales of mugams,

just as a mugam symphonies are symphonies based on mugams. Ordinary

jazz is marked by metered rhythm. But mugam jazz does not follow

a metered system. Both rhythm and scales are improvised.

By the beginning of the early 1960s, Vagif was gaining recognition

outside of Azerbaijan as a jazz musician. In 1966, Willis Conover,

conductor of the "Jazz Time" radio program, announced,

"Vagif Mustafazade is an extraordinary pianist. It is impossible

to identify his equal. He is the most lyrical pianist I have

ever known."

That year, Conover came to the Jazz Festival in Tallinn, Estonia,

after visiting several European countries. He expressed his disappointment

with the American jazz he had heard there and complained that

"no one can play American jazz like Americans do."

When the participants heard this, most of them changed their

programs and concentrated more on their own "national"

pieces. Everybody expected Vagif to do the same and play one

of his mugam-jazz arrangements. But instead, he challenged Conover

and surprised everyone by playing Gershwin's "The Man I

Love." As he finished the piece, Conover stood, applauding

and shouting "Bravo!" Vagif had proved that he could

play American jazz, as well as, and possibly even better than,

most Americans. He took first place at the festival.

Despite this worldwide recognition, Vagif still had trouble finding

support at home. Some of his friends, including myself, who taught

at the Music Conservatory (now known as the Music Academy), were

unable to secure a position for him there. Decision makers always

complained that he was too involved with jazz. It wasn't until

1964 that he acquired a position, thanks to the efforts of Rafig

Guliyev and Zohrab Adigozalzade, who both taught there.

Aziza is Born

Then

Vagif left for the Republic of Georgia where he organized the

famous "Orera" group and helped train famous musicians

such as Tomaz Kurashvili. It was also in Georgia that he met

a young woman, Elsa, whom he later married. Vagif already had

a daughter by his first marriage by the name of Laleh who would

grow up to become an extraordinarily talented classical pianist

and would win the Grand Prize for Piano in Epinal, France, in

1991.

Then a daughter was born to Elsa, and they named her, Aziza.

Now in her late 20s, she has became one of the stars of jazz

music, just like her father was. In 1978 Vagif took first place

for his performance of "Waiting for Aziza," at the

8th International Jazz Festival in Monaco.

Other jazz pianists had a great respect for Mustafazade. Once,

when Vagif was playing in the Iveriya Hotel in Tbilisi, the famous

American jazz pianist and master of blues, B. B. King, heard

him and remarked, "Mr. Mustafazade, they call me the 'King

of the Blues,' but I sure wish I could play the blues as well

as you do."

Vagif's Death

Vagif's

death was a shock to many people. He was only 39 years old when

he died on stage while performing in Tashkent (Uzbekistan) in

December 1979. Somehow the tragedy came as no surprise to me.

I had, somehow, anticipated it. Every time I used to see him

at the piano, I realized that he was as taut as a string. I knew

that he would not be able to survive music for very long.

Three months later, on March 16, 1980, I helped to organize a

Memorial Night at the Actors' House devoted to his memory. So

many people came to pay tribute that we had to set up loudspeakers

in the lobby and in the street. There just wasn't enough room

in the hall. A few days later Conover devoted his 45-minute radio

program entirely to Vagif.

Vagif's mother spent the last years of her life officially seeking

permission to convert their apartment into a home museum in honor

of her son. She managed to remodel the area and gain access for

the museum to two additional rooms adjacent to the original quarters

where they had once lived. The Vagif Mustafazade Home Museum

was opened on March 1, 1988, eight years after Vagif's death.

Eight years later, in January 1996, Ziver Khanum, too, also passed

on.

The museum is open to the public-this apartment where Vagif,

I and others spent so many intense, pleasurable hours and days

straining to hear Radio BBC and experimenting and improvising

on the piano.

It's a very simple museum. Lots of photos are on the walls. The

piano is still there in the main room, as is the old wooden box

radio.

It's amazing how those jazz programs that we listened to some

30-40 years ago were able to penetrate the stubborn walls of

totalitarianism, and how the sound that eventually emerged still

affects how jazz is played in Azerbaijan today.

Vagif Samadoglu,

the author of this article, is the son of the famous poet Samad

Vurgun. He studied classical music professionally and graduated

from the Academy of Music and graduate studies at the Moscow

Conservatory. He won the 1962 Music Festival in Baku. He now

devotes all his time to writing poetry. His most recent book,"Man

vurdayam" (I Am Here), was published in Baku in 1996 (Azeri

Cyrillic). See AI 4.1, Spring 1996, for Vagif's article about

his father, Samad Vurgun.

Vagif Mustafazade's Home Museum is located in the Inner City

(Ichari Shahar) at Duksovski Corner, Vagif Mustafazade Corner

4. Tel: (99-412) 92-17-92.

From

Azerbaijan

International

(5.4) Winter 1997

© Azerbaijan International 1997. All Rights Reserved.

Back to Index AI 5.4 (Winter

1997)

AI Home |

Magazine

Choice

| Topics

| Store

| Contact

us

|